1

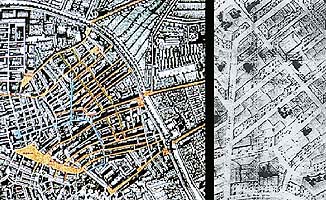

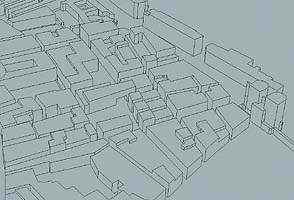

El asentamiento del barrio de Velluters se

produjo en la parte occidental de la ciudad, entre las murallas musulmana

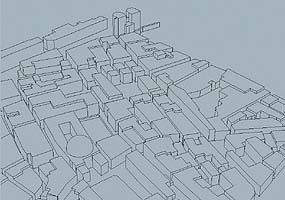

(s. XI) y cristiana (s. XIV). Cuando se construyó esta última, recogió

un pequeño núcleo de población -Barrio de las Torres- que se dedicaba a

la producción sedera. Esta actividad introducida por los árabes fue la

principal del barrio entre los siglos XV y XVIII, marcando su desarrollo

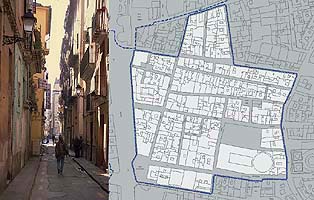

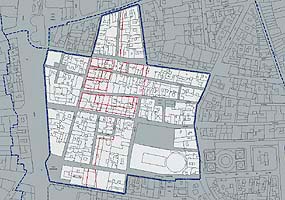

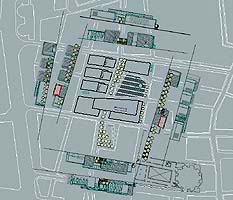

urbano / The Velluters quarter developed in the western part of the city,

between the Moorish (11th c.) and the Christian (14th

c.) walls. When the latter were built a small nucleus, the Barrio de las

Torres [Towers Quarter], was brought within the city. Silk making, an

activity introduced by the Moors, was the main occupation of this quarter

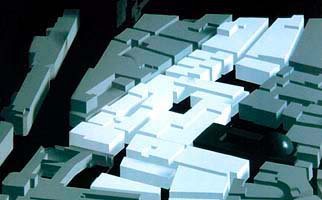

between the 15th and 18th centuries and shaped its

urban development.

2

Se trata de un tejido de gran racionalidad,

sin jerarquía viaria, en el que predominan itinerarios de gran longitud

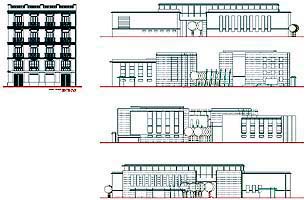

en sentido oeste-este de penetración en la ciudad, con calles de escasa

anchura y muy próximas entre sí.

La trama urbana está íntimamente relacionada con la tipología de

vivienda menestral cristiana: casas de poca altura, sobre pequeñas

parcelas, en las que se aunaba la vivienda y el obrador.

El tejido urbano que hoy encontramos es prácticamente idéntico -al menos

a nivel de planta- al que se aprecia en el plano del padre Tosca de

principios del XVIII / The fabric is very rational although the streets

lack any hierarchy. The routes are mainly very long and run west to east,

the direction of entrance into the city. The streets are narrow and very

close to each other.

The urban layout is intimately related to the typology of Christian

artisan housing: little height, on small plots, combining dwelling and

workshop.

The urban fabric found here today is practically identical, in its ground

plan at least, to that which is shown on the early 18th c. map

drawn by Padre Tosca.

3

En la segunda mitad del XIX Valencia

duplicó su población. La densificación del tejido afectó especialmente

a Velluters que -tras una caída de la producción sedera- sufrió su

primera transformación: edificios de hasta cinco alturas se construyeron

sobre una trama inalterada a partir de limitadas agrupaciones parcelarias.

Son edificios plurifamiliares de alquiler para la clase trabajadora, de

baja calidad constructiva y que sustituyeron, de forma masiva, a las

antiguas viviendas obrador / The population of Valencia doubled in the

second half of the 19th c. The increasing density of the city

particularly affected the Velluters quarter which, following the decline

of the silk industry, suffered its first transformation as buildings of up

to five storeys were built on limited groupings of plots without altering

the urban layout. The old houses with workshops were replaced en masse by

poorly built multi-family buildings for renting to the working classes.

4

niciados los procesos de crecimiento

demográfico, se derribó la muralla cristiana en 1.865 y se sucedieron

los planes de ensanche y de reforma interior. El Plan de Javier Goerlich

-1.928- recogía la propuesta que veinte años antes hiciera Federico

Aymamí de apertura de la Avenida del Oeste. Ésta, referenciada en las

propuestas de Haussmann para París de mediados del XIX, se amparaba en la

adecuación a formas de vida más higienistas así como en la

accesibilidad del tráfico rodado / As the population of the city grew,

the Christian wall was pulled down in 1865 and successive expansion and

internal remodelling plans followed each other. Javier Goerlich’s 1928

plan returned to Federico Aymamí’s proposal of twenty years earlier to

open up the Avenida del Oeste. This was inspired by Haussmann’s mid 19th

c. plans for Paris and was defended on the grounds of a more hygienic life

style and accessibility for wheeled traffic.

5

La Avenida del Oeste, ejecutada

parcialmente, produjo graves consecuencias para el barrio. Con 25 m. de

anchura y edificios de hasta 12 plantas mutiló las conexiones de

Velluters con el resto de la ciudad. Se precipitó un proceso de deterioro

en el interior del barrio que vino a añadirse a la decadencia arrastrada

desde finales del siglo pasado / The Avenida del Oeste was carried out in

part, with grave consequences for the Velluters quarter. This 25 m wide

avenue with buildings up to 12 storeys high amputated the connections

between Velluters and the rest of the city, precipitating further

deterioration within a quarter that had been suffering an ongoing decline

since the end of the previous century.

|

6

El elevado grado de deterioro desembocó en

masivos derrumbamientos en las últimas décadas. El despoblamiento, la

baja calidad constructiva, el inexistente mantenimiento de edificios donde

residen grupos sociales envejecidos y de escasos ingresos, precipitaron el

proceso. Grandes bolsas de solares son utilizadas como aparcamientos dada

la escasez de esta dotación en el centro de la ciudad. En el interior del

barrio la prostitución ha derivado en el menudeo de droga y en la

delincuencia / The high degree of deterioration has resulted in massive

building collapses over recent decades. Depopulation, poor building

quality and the non-existent maintenance of buildings inhabited by an

ageing low-income population precipitated the process. Great pockets of

vacant sites are used for parking, due to the lack of this facility in the

centre of the city. Prostitution within Velluters has turned into small

time drug-dealing and crime.

7

El Plan General de Ordenación Urbana de

Valencia -1.988- pospuso la ordenación del Centro Histórico al

desarrollo de Planes Especiales. El de Velluters -1.992- prescribía la

renovación de su zona central de norte a sur. Ésta se materializaba en

dos aspectos: la apertura de un nuevo eje desde la calle Quart a la calle

del Hospital y la producción de espacios libres vinculados a dicha calle.

Establecidas esas pautas generales, relegaba el proyecto urbano de esa

zona central a la elaboración posterior de Estudios de Detalle.

En 1.996, coordinada desde la Oficina RIVA, se fijó y programó una

propuesta definitiva de intervención. Se concretó el esquema genérico

de eje central que planteaba el Plan Especial y se hizo dosificando en él

los usos residenciales, las instalaciones comerciales y aquellas

actividades que provocan centralidad.

Un corredor norte-sur en el que se distribuyen estratégicamente los usos,

estableciendo la relación correcta entre edificios y espacios libres /

The General Plan for the Urban Zoning of Valencia of 1988 left the zoning

of the Historic Centre to Special Plans. The Special Plan for Velluters of

1992 prescribed the renovation of its central area from north to south.

This was to take shape in two ways: a new axis from calle Quart to calle

del Hospital and open spaces linked to the latter. Having established

these general principles, it relegated the urban project for this central

zone to subsequent Detailed Studies.

In 1996 the Oficina RIVA coordinated the drawing up and scheduling of a

definitive action proposal. The general scheme of a central axis

established by the Special Plan was given concrete form, with residential

uses, commercial premises and activities that promote centrality dotted

along it.

On this north-south corridor, the uses are distributed strategically and

an appropriate ratio of buildings to free spaces is established.

8

La Generalitat Valenciana, a través de la

Oficina RIVA, quedó encargada de concretar la ordenación entra las

calles Quart y Camarón, y el Ayuntamiento de Valencia entre Viana y Roger

de Flor. Cada Administración gestionará, de forma directa, las Unidades

de Ejecución que se deriven de dichos ámbitos / The Valencian Regional

Government, through the Oficina RIVA, took charge of the zoning from Quart

street to Camarón street and Valencia City Council from Viana street to

Roger de Flor street. Each of these levels of government will administer

the Execution Units for the said areas directly.

9

Este área se caracteriza, en un primer

nivel de aproximación, por la escala del espacio urbano: las

sobreelevaciones del XIX sobre la trama original generaron una volumetría

urbana desproporcionada.

Asimismo se detecta una gran fragmentación de los frentes de fachada.

Este hecho, denominador común de todo el Centro Histórico, se ve

acentuado aquí debido al reducido tamaño de las parcelas. Aquí

predominaba, hasta finales del XVIII, la vivienda obrador, asentándose

las edificaciones del XIX sobre primitivas parcelas o sobre limitadas

agrupaciones parcelarias / At first sight, the characteristic feature of

this area is the scale of the urban space: placed on the original layout,

the additional height of the 19th c. buildings gave rise to a

disproportionate urban volumetry.

Another feature is the fragmentation of the façades. This is common to

the entire Historic Centre but is accentuated here by the smallness of the

plots: until the end of the 18th c. the predominant type here

was the house with workshop and the 19th c. buildings were

placed on the original plots or limited groupings of them.

10

La arquitectura es en su mayor parte de

escaso valor, siendo muy pocos los edificios protegidos del ámbito. La

calidad constructiva es baja, la conservación deficiente. Hay un

importante número de construcciones abandonadas o ruinosas. Las viviendas

no cumplen, en su mayoría, las mínimas condiciones de habitabilidad

actuales. La población residente se convierte aquí en causa y efecto del

escenario físico / The architecture is generally of little value and

there are very few listed buildings in the area. The building quality is

low and conservation poor. A great number of buildings are abandoned or in

a ruinous state. The majority of the housing does not meet the current

minimum requirements. The resident population is both a cause and an

effect of the physical environment.

|

11

La solución adoptada tiene en cuenta el

retorno al barrio de aquellos colectivos sociales que son recuperables

aunque, dada su baja capacidad económica, requerirán ayudas para la

compra o alquiler de viviendas.

Para concretar el escenario social se partió de una detallada toma de

datos en campo. A partir de un modelo de ficha se obtuvieron aquéllas

circunstancias personales y familiares que ayudaran a perfilar las

características de la población. Se obtuvo información sobre los

niveles de ingresos, situación laboral, composición familiar, edades,

régimen de tenencia de las viviendas,... / The chosen solution takes into

account the return of social groups that could be brought back to the

quarter, although their low income level means that they would require

assistance in buying or renting housing.

The starting point in defining the social scenario was a detailed field

survey, using a questionnaire of personal and family circumstances to

determine the characteristics of the population. Information was obtained

on income levels, work situation, family membership, ages, type of housing

tenure, etc.

12, 13, 14, 15

Rechazada la recuperación pieza a pieza,

viable en otros ámbitos con características arquitectónicas de mayor

calidad, se plantea una operación decidida de recualificación urbana.

Tras una detenida lectura de la trama se persigue la autonomía de la

intervención en sintonía y continuidad con el tejido en que se inserta;

identificar la actuación contemporánea, no relegar únicamente al

lenguaje arquitectónico la lectura de modernidad: la pieza urbanística

también es nueva.

Un conjunto dotacional como nodo de atracción -destinado a usos

educativos o residenciales vinculados a ellos- atraerá gente joven a un

barrio envejecido. Las buenas comunicaciones por su proximidad a la ronda,

su cercanía a un colegio, y la equidistancia a potentes áreas de

actividad como la biblioteca y el núcleo cultural del Carme, propiciarán

el recorrido interno peatonal por este lado poniente del Centro

Histórico.

La ordenación trata de hacer una aproximación a la escala del lugar,

así como abstraer las leyes de formación del tejido adaptándose a las

nuevas necesidades del proyecto urbano. Se pretende la configuración de

manzanas compactas abstrayendo y regularizando lo existente, con especial

cuidado en las proporciones que se establezcan entre el espacio ocupado y

el espacio libre. La forma y ubicación de los edificios trata de captar

el espíritu del lugar creándose un área densa en torno al espacio

central. En la concepción del área ha primado conceptualizar un trazado

histórico en sentido oeste-este. Así, pese a la introducción de nuevos

ejes viarios ortogonales, las piezas edificadas se disponen de forma

longitudinal recordando la anterior estructura. Se busca una composición

de conjunto de los edificios unitaria y autónoma, un elemento singular y

una seriación de tres piezas perfectamente paralelas en un intento por

racionalizar la propuesta. En la pieza singular -que mantiene

aproximadamente las alineaciones de la manzana precedente y permite el

paso a través suyo del eje norte-sur mediante un pasaje de dos alturas-

se dispondrá un potente equipamiento, mientras que para los tres

edificios seriados se piensa en edificación residencial de tipo

comunitario, residencias de estudiantes, con disposición interior de

estancias con orientación norte y sur al igual que las pretéritas /

Having rejected a building-by-building recovery which would be feasible in

other situations where the architecture is of greater quality, a

determined urban upgrading operation was proposed.

Following a careful reading of the urban layout, the aims were: an

autonomous intervention that would also be a continuation of the fabric

into which it is inserted and be in tune with it; and identification of

the contemporary work, not leaving the reading of its modernity to the

architectural language alone: the work of urbanism is also new.

A group of facilities as a focal nucleus, for educational uses or

residences related to these, will bring young people into an ageing

quarter of the city. Good communications thanks to the nearby inner

ringroad, the proximity of a school and the similar distances of powerful

poles of attraction such as the library and the Carme cultural centre will

encourage the use of internal pedestrian routes on this western side of

the Historic Centre.

The zoning attempts to approach the scale of the place and to distinguish

the laws of formation of the fabric, adapting itself to the new needs of

the urban project. Compact city blocks are shaped by abstracting and

regularising existing ones, paying particular attention to the proportion

of occupied to open spaces. The form and location of the buildings tries

to catch the spirit of the place, creating a dense area around the central

space. The conceptualisation of a historic west-east layout was at the

forefront of the concept of the area. Consequently, although new, straight

roads are introduced the buildings are arranged longitudinally, recalling

the former structure. A unitary, autonomous overall composition of the

buildings, an individual element and a series of three perfectly parallel

pieces attempt to rationalise the proposal. The individual element, which

retains the approximate alignments of the former block and has a

two-storey passage through which the north-south axis passes, contains the

powerful attraction of the public service facilities, while the three

serial buildings could be a community type residential block, for students

for instance. The internal arrangement of the rooms would give them the

north and south orientation of the former buildings.

|

16

Se plantea un importante dotación de

aparcamientos subterráneos.

Se priman los recorridos peatonales proyectándose dos espacios libres de

diferente carácter. El situado más al sur tendrá un tratamiento

ajardinado vinculado a edificación residencial. El otro se concibe como

plaza cívica en torno a la cual se ubican los edificios dotacionales. La

materialización de la urbanización da continuidad a los dos espacios

libres, que se unirán por debajo del pasaje a través de un paseo

arbolado. La plaza deberá contener poco mobiliario urbano cediendo el

protagonismo a la arquitectura. Una urbanización tradicional, con

materiales naturales y lenguaje de hoy / A major provision of underground

car parks is planned.

Emphasis is placed on pedestrian routes and two open spaces of differing

character are planned. The southern one will be landscaped and related to

the residential buildings. The other is conceived as a civic square

surrounded by public service buildings. The materialisation of the

urbanisation provides continuity between these two open spaces, uniting

them through the passage by means of a tree-lined walk. The square must

contain little urban furniture so that attention is drawn to the

architecture. The urbanisation is traditional, with natural materials and

the language of today.

17

La inconcreción de los usos dotacionales

en el momento de redacción del documento impedía hacer preceptiva desde

el planeamiento una imagen arquitectónica. Nos limitamos a exigir un

anteproyecto global de todos los equipamientos e incluimos en el Plan un

plano no normativo cuya intención proyectual es -al igual que en la

ordenación volumétrica- referenciarse en las preexistencias tomando de

éstas, sólo, aquellas leyes de composición que permitan una lectura de

continuidad con el contexto arquitectónico / The lack of precise

knowledge of the future public service provision when the document was

drawn up prevented us from providing an architectural image of a

prescriptive nature. We limited ourselves to demanding a preliminary

global proposal for all the facilities and to including a non-prescriptive

plan in the Plan. The planning intention that underlies this plan, and the

volume zoning, is to refer to the existing buildings but to take nothing

from them other than the laws of composition that will provide a reading

of continuity with the architectural context. |