Obsesionado como estoy por el comportamiento de quienes me rodean, y siendo como soy observador profundo y descarado de sus actitudes, podría definir al ciudadano que leerá este artículo como personaje con las siguientes características constantes:

1. Búsqueda

cotidiana de la pasta, para una supervivencia soportable.

2. Cultura telegráfica, basada en la lectura de las ediciones fin de

semana de El País o El Mundo, cuyo contenido necesitan recitar

inmediatamente al amigo o familiar próximo más paciente.

3. Utilización del tiempo libre, e incluso tiempo robado o trampeado, para

consumir del modo más descarado y ostentoso posible.

Dicho lo cual, podemos continuar profundizando en las tres o cuatro cosas que nos caracterizan a todos los componentes del grupo social al que pertenecemos, o dejamos las cosas así, que tampoco pasaría nada. Pero este debe ser un texto sobre Centros Comerciales, con 8/10 páginas y fotografías, para una revista especializada que ha nacido fuerte, con calidad de contenido y aspecto, por lo que debo seguir escribiendo para quienes no han conectado la TV y dejado este escrito sobre el sofá.

Punto uno

Localizar y conseguir dinero para sobrevivir es el día a día de

cualquier oficio, incluso para arquitectos y excepto para funcionarios.

Generalmente nunca llegamos a reunir lo suficiente para obtener aquello

que nos da vueltas en la cabeza hace algún tiempo, no necesariamente

comprándolo pero sí al menos siendo conscientes de que lo tendríamos en

cuanto nos apeteciera.

Confirmada nuestra capacidad de posesión, poseemos aquella cosa y empezamos a desear la próxima. Ocurre con un coche, con un equipo de música, con unos zapatos o simplemente con la cena, en cuanto hemos hecho la digestión de la comida y un amigo nos habla de un restaurante muy barato que ha descubierto en el que se come de muerte.

Con estos logros cotidianos, pequeños o grandes, caros o baratos, pero necesariamente frecuentes, vamos afianzando nuestra personalidad, convencidos de que nuestro carácter lo conforman o al menos lo condicionan las cosas que poseemos, o mejor, que hemos decidido poseer a diferencia de las que poseen, o mejor, han decidido poseer otros.

Así comienzan a configurarse personajes con gustos y aficiones por la música, por la literatura, la pintura, la fotografía, los viajes, el cine, etc., personajes cuya cultura, de la que hablaré en el punto siguiente, parece ser sólida y basada en aquello de lo que hay mucho en su casa, o en las estanterías de su casa. O en su tiempo libre, o en la utilización de su tiempo libre.

Cuando esta capacidad de consumir es desproporcionada con respecto al ocio, es decir, utilizamos más tiempo buscando o comprando el objeto que utilizando o saboreando el objeto, nuestra afición-hobby enferma, llegando a cuadros clínicos cuya gravedad es alarmante, porque convulsiona al individuo de tal modo que le impulsa necesariamente a trabajar mucho más de la cuenta y de un modo histérico.

Es el gran trabajador, el que ha nacido para trabajar y no sabe hacer otra cosa más que trabajar, según sus seres queridos.

Punto dos

No están mal los semanarios de los periódicos, o las separatas Tentaciones,

Babelia, etc. Para mí, el mayor encanto es que no hablan de

política, como el 90% de las páginas del periódico correspondiente, al

menos de un modo descarado.

Ponen el dedo en la llaga hablando de lo que queremos consumir, y nos orientan, haciendo pruebas comparativas, itinerarios, incluso calificaciones numéricas al desayuno de los hoteles.

Nos enseñan el

universo que debemos conocer y no otro. Nos dan la ración de información

que configura nuestra cultura media, y nos hace sentirnos

satisfechos :

ya sé lo que puedo comprarme desde el próximo lunes. Soy lo

suficientemente culto como para comunicarme con los demás a lo largo de

una cena en corro, sin sentirme excluido de cualquier tema de

conversación. Yo también sé recitar El País.

Punto tres

En este punto es donde aparece un americano en España hace

aproximadamente quince años y dice : Tienes tiempo, no mucho, y

necesitas ver dónde es más barato este microondas sin necesidad de

recorrerte toda la ciudad, aparcando con riesgo de grúa en siete sitios

distintos, o de ruina por parking. He concebido para ti este paraíso

artificial que además de calor en invierno y fresquito en verano, no

necesitas paraguas, puedes olvidarte de la grúa y vas a encontrar juntos,

en sangrienta competencia, a todos los comerciantes desparramados por la

ciudad, para mayor beneficio y comodidad tuya.

Con esta historia tan bonita nacieron los Centros Comerciales en nuestro país.

2. ÁREAS COMERCIALES

En mi época de

profesor de proyectos, cuando intentaba ayudar a los alumnos tratando de

que concibieran una imagen o la esencia simplificada o simbólica de un

proyecto en estudio, solía repetir que un mercado, el mercado tradicional

que se repite en nuestra geografía, es básicamente una fuente con un

paraguas. El ejemplo inmediato era el mercado de Tavernes Blanques, que

por las tardes cuando los puestos instalados cada día desaparecían,

quedaba reducido a una fuente para limpiar y una cubierta elemental.

Siguiendo el juego de las simplificaciones, si al conjunto anteriormente definido le añadimos una nevera, aparece el supermercado. Y si le poníamos una plaza de aparcamiento, un hipermercado.

Como Europa es tierra de mercados, los franceses nos propusieron la Gran Superficie, que además del grifo, del paraguas y del coche, facilitan un carrito para que la compra sea mayor, te atraques de comprar y les dejes más pasta. Muy francés.

Pero lo americano tenía más tirón, no olía tanto a comida y además habían tenido la habilidad de convertir un páramo en la calle de Serrano madrileña o en la de Colón valenciana. Y los franceses hacen un poco más grande la ya de por sí Gran Superficie, hasta el punto que la gente ya no sabe que hacer con el carrito, convertido en un incordio entre zanahorias, camisas y hamburguesas., porque junto al hipermercado tirón aparece en descarada competencia con el auténtico Centro Comercial una galería cada vez más complicada de tiendas diversas. Algo así como si el hiper promotor ganara más dinero alquilando locales comerciales que vendiendo perecederos.

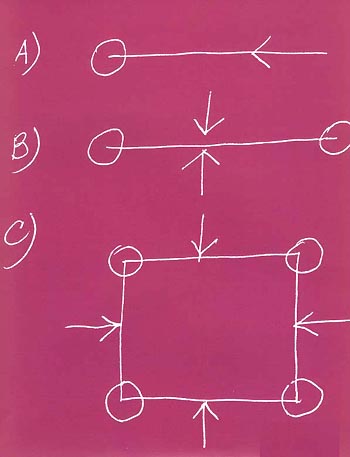

La configuración básica de los centros comerciales responde a cualquiera de los siguientes esquemas:

A. Motor (Gran Almacén) único: el recorrido desde la entrada al Centro lleva al Gran Almacén.B. Dos motores: Situados como polos en cada uno de los extremos de la calle comercial o mall. El acceso se produce por cualquiera de los lados del mall o por ambos. Este último es el caso de Nuevo Centro en Valencia, con la peculiaridad que el motor es único pero desdoblado físicamente para duplicar su tirón.

C. Varios motores, generalmente cuatro, y situados en cada uno de los vértices de un cuadrado, a través de cuyos lados se produce el acceso al Centro Comercial. Este es el esquema del Mall of America que veremos luego.

Centrándonos en nuestro territorio, nos encontramos con una excesiva cantidad de "centros comerciales". Con respecto al modelo americano de referencia, el entre-comillado intenta puntualizar la gran diferencia con un auténtico Centro Comercial.

El motor es distinto en el original y en la copia : en aquel es un gran almacén o varios, destinado básicamente a la moda y al hogar utilizando los conceptos tradicionales que empiezan a quedarse cortos ; en éste se ha copiado el motor con la alimentación, que en mi opinión comete el error de mezclar la compra -castigo de la comida diaria, con la compra ociosa-lúdica.

El crecimiento del modelo americano se ha producido con aumento del tamaño, como consecuencia de la integración de más motores y por tanto la acumulación de más tiendas bajo su cobijo. Es decir, este crecimiento no ha supuesto una variación o degeneración del concepto matriz, todo sigue igual, pero más abundante y más grande. Nuevo Centro, en cuyo proyecto inicial participé, y en cuya puesta al día actual intervengo quince años después, responde como pocos Centros Comerciales al modelo americano original.

3. ARQUITECTURA COMERCIAL

Pretender

hacer Arquitectura con mayúsculas al proyectar un centro comercial es

equivocar los términos. La vida comercial es vertiginosa, cambiante, y su

código constructivo muy definido, lo que nos lleva a una exigencia

ambiental escasa o innecesaria en imaginación, en cuanto ésta se refiera

a la aportación formal del arquitecto.

Incluso metidos en la coctelera el grifo, el paraguas, la nevera, el coche y el carrito, agitados todos ellos con criterios puramente comerciales, poco queda o muy arriesgado es añadir algún ingrediente arquitectónico al combinado : probablemente sólo admita una guinda o una rodaja de limón. Lo veremos más fácilmente y con menos apasionamiento profesional si observamos la génesis de un mercadillo callejero. Comercialmente perfecto, como son todos ellos, ordenarlo o racionalizar su espontaneidad sería un error, no tendría sentido.

Una paella bien hecha no necesita una mano arquitectónica. Guisarla y comerla requiere un sitio, una mesa con sillas y poco más. El exquisito diseño de un restaurante nada tiene que ver con la calidad de la comida.

Pues bien, en términos comerciales, donde el marco arquitectónico es de vida corta y mutante, y el metro patrón es el dinero, la arquitectura llega a su nivel máximo de aspecto de servicio. Los edificios seguramente no pasarán a la Historia de la Arquitectura, difícilmente podrán tener en el futuro otra utilización, e incluso acabarán su vida con un aspecto totalmente distinto al proyectado por imperativo de evolución comercial. El arquitecto, erigido en portavoz de la colectividad comercial, puede decir como mucho dónde hay que poner el grifo y qué grande ha de ser el paraguas, utilizando, si es honesto con los demás y consigo mismo un lenguaje apropiado para que el consumidor, diverso y plural entienda el recinto, y su lectura al ser fácil contribuya a la compraventa, máxima satisfacción de los mercaderes, nuestros clientes.

Nada más lejos de mi intención que cuestionar la calidad profesional de Rafael Moneo, a quien admiro como persona y como arquitecto. Pero nada más lejos de un centro comercial que el premiado proyecto por terceros titulado L´ Illa, en Barcelona. La pregunta es. ¿Qué criterios han de prevalecer en la génesis de un proyecto comercial, para satisfacer o atraer en primera instancia a los comerciantes que han de establecerse, y a continuación , con el mismo proyecto, a los usuarios compradores que van a mantener el centro abierto y vivo con su presencia ? La pregunta, en mi opinión, tiene una respuesta con dos aspectos muy diferenciados.

El primero se basa en la ubicación , y son las razones por las que el comerciante está allí, junto a aquellos y frente a los otros., razones totalmente estratégicas, en las que el arquitecto ni opina.

El segundo se basa en la configuración del paisaje comercial de las zonas comunes, porque las de cada tienda dependen totalmente del titular que las adquiera, no del autor del centro. Hay que generar un paisaje atractivo, grato, legible y cómodo, nada más y nada menos. Pero creo que es escoger la copa para el combinado y ponerle la guinda , y como mucho, la rodajita de limón. Quien hace el cóctel y quien se lo bebe son otros. Duro y real.

4. EJEMPLOS

El Mall of America,

como su nombre indica, intenta ser el Centro Comercial más grande de los

Estados Unidos. Con una superficie de un millón de metros cuadrados,

sólo es inferior en todo el mundo al de Edmonton (Canada), de acuerdo con

los datos recientes de libro Guiness de los Records.

Un millón de m2 son muchos, tantos que resulta imposible recorrerlo totalmente en un día, yendo aprisita. Usarlo es más complicado, porque además de cuatro grandes almacenes muy famosos en USA, posee muchas tiendas de más de 1.000m2 de superficie, casino, acuarium con tiburones que te dan los buenos días, y una especie de Disneylandia-Feria con todo tipo de carruseles de los de gritar, que hacen las delicias de los pequeños y algunos mayores, mientras el resto de la familia funde la pasta.

Todo el espacio posible es cubierto y la atmósfera artificial permite que varios millones de compradores anuales estén a gusto dentro del recinto. El coche —sabia medida— está ubicado en edificios aparte, dedicado exclusivamente a aparcamiento, por lo cual no se convierte en módulo de nada más que de sí mismo. Un encanto.

Está situado junto al aeropuerto de Minneapolis-SaintPaul, ciudades gemelas (Twin Cities), más bien siamesas, unidas o separadas por el Misissippi, que suman 4 millones de habitantes, pero que no son la única fuente de clientes del centro.

El Mall of America se alimenta del resto del estado de Minesota, cuya ciudad inmediata siguiente en población es de 100.000 habitantes, y puedes hacer perfectamente muchos tramos de 100 o 200 Km. Por carretera sin ver un poblado.

Todo el estado, y también los estados limítrofes usan este centro con la misma frecuencia que los valencianos vamos por ejemplo a Nuevo Centro, por eso su ubicación pegada al aeropuerto, porque el avión es el vehículo de acceso más frecuente.

Estamos por tanto frente a una dimensión comercial distinta. Mayor tamaño, mayor oferta, mayor área de influencia, gama completísima de servicios que satisfacen al niño y al abuelito, al militar y al paisano, al soltero, al casado y al arrejuntao, con ruta del bakalao incluida y con uno de los Planet Hollywood más grandes del mundo, como quien monta una croissanterie.

El grado de influencia y el tirón es tal, que la mayor concentración de hoteles en Minneapolis se da alrededor del Mall. La gente reserva un hotel, toma el avión y viaja en familia para comprar durante varios días. ES-PEC-TA-CU-LAR.

Luego viene todo eso de que al tener la zapatería 1.000 m2 y otros tantos de almacén, el empleado que nos atiende lleva un micrófono con auriculares para pedir el 43 al almacén y no romper la venta yéndose él mismo al depósito a por el par. Y el Tom Cruise del bar que él solito atiende a 30 o 40 clientes en la barra, sonriendo, y sin que nadie necesite quejarse lo más mínimo. Como decía un cartelito en el escaparate de una tienda en New York junto al primer teléfono inalámbrico que vi hace 20 años: ¿Y mañana qué, América?

Aceptando que nieva fuerte durante 6 meses del año, Minneapolis decidió moverse con facilidad por un nivel superior para evitar el hielo. Al igual que en otra ciudades canadienses, como Calgary, se ha producido un pasillo cerrado, de muchísimo uso, que recorre todo el centro de la ciudad, convirtiéndose en un mall por donde va la gente de un sitio a otro y adonde necesariamente tenían que acudir los comerciantes a vender algo. Con el precedente histórico del puente Viejo en Florencia, y la referencia doméstica del puente de madera que llevaba a la estación del trenet eléctrico junto a las Torres de Serranos, que se llenaba de ofertas mediante kioscos y tenderetes en los años 40/50, es fácil comprender que el citado pasillo peatonal se ha convertido en una senda comercial.

Pues bien, el resultado es que por el nivel de asfalto van los vehículos, pero la gente, con calor en invierno y fresquito en verano, ha decidido moverse por este nivel superior, que además tiene ahora el atractivo de la oferta comercial (pasear viendo escaparates) y los comerciantes han puesto todas sus municiones en este nivel, convirtiéndolo en una selva en la que hay que ir apartando la oferta con un machete para abrirse paso, tal es el agobio.

Ya no hay

escaparates en las aceras, para qué. Las fachadas han sido

trasladadas al nivel de peatones, y como no siempre ha sido fácil trazar

las calles peatonales a través de los edificios, con frecuencia hay que

atravesar la planta de caballeros de unos grandes almacenes para ir al

notario o a un concierto. Se llama Nicolet Mall.

…

Volvamos a la arquitectura. No puede proyectarse un centro comercial sin

conocer estos precedentes.

Hay que replantearse el que los Mayordomo tengan en Valencia más zapaterías que Bancaja agencias. Algo no funciona bien cuando diseccionamos en vez de unir para la fuerza.

Estamos volviendo a la tienda de barrio, perdón, pequeño comercio, sólo que situadas dentro de las nuevas calles que son los centros comerciales. En una ciudad como Valencia no puede haber más centros comerciales que hospitalarios, o que institutos. Debe haber mucho de todo, concentrando, aunando y multiplicando los servicios.

Centrar o centralizar comercialmente quiere decir poner todas las fuerzas en un recinto para mejorar la organización y el servicio, y que los treinta y siete encargados de las zapaterías sean los treinta y siete empleados de calidad de una gran tienda en un Gran Centro Comercial.

Esta puede ser una de las misiones del arquitecto, o de una especialización del arquitecto que interviene en la génesis de los centros comerciales, como interviene en el modo de habitar. El arquitecto del centro comercial no debe decidir solamente el color y la textura de los paramentos.

Los hipers están bien como mercados. Se come tres veces al día y hay que comprar comida frecuentemente, casi diariamente. Al aprovechar que el Pisuerga pasa por Valladolid, colocando tiendas en la senda comercial anexa, de un modo tímido inicialmente, y exageradamente ahora, los hipermercados, jugando a centros comerciales, se han multiplicado de un modo desenfrenado, y empezamos a fornicarla. Sí, porque los Mayordomo quieren (y deben) estar también en el próximo que se abra.

As a person who is obsessed by the behaviour of those around me and as a profound and shameless observer of their attitudes, I might define the citizen who will be reading this article as a person with the following constant traits:

1. Daily hunt for the cash required for bearable

survival

2.Telegraphic culture based on reading the weekend editions of El País or

El Mundo [national newspapers], the contents of which they then need to

recount to the nearest friend or family member with the most patience.

3.Use of free time, or even stolen or cadged time, to consume as brazenly

and ostentatiously as possible.

Having said all this, we can go deeper into the three or four things that are typical of all the members of the social group we belong to or we can drop the whole subject; which would be fine as well. However, this is supposed to be a piece on shopping centres, 8 to 10 pages long with photographs, for a specialist journal that has started off on a good foot with a quality content and look, so I had better carry on writing for the people who have not yet switched on the TV and left this lying around on the sofa.

Point one

Except for civil servants, finding and getting money to survive is the

daily grind in any job, even architecture. We usually do not manage to get

enough to get hold of whatever it is that has been going round and round

in our heads for some time, not necessarily buying it, but at least

knowing that we would get it sometime, when we felt like it.

Having confirmed our capacity for possession, we possess that thing and begin to want the next one, whether it be a car, a music centre, some shoes or just supper, even though we have barely had time to digest lunch, when a friend mentions a really cheap restaurant he has discovered where the food is something else.

We continue to affirm our personality with these daily achievements, small or large, cheap or expensive, but necessarily frequent, convinced that the things we possess, or rather, that we have decided to possess, as opposed to those that other people possess, or rather, have decided to possess, shape or at least influence our character.

In this way, characters begin to be shaped, with tastes and interests in music, literature, painting, photography, travel, the cinema, etc., characters with a culture (which I will talk about in the next point) that seems solid, based on what they have a lot of in their home or on their shelves at home; or on their spare time or their use of their spare time.

When the capacity for consumption is out of proportion to the spare time available, in other words, when we spend more time looking for or buying the object than using and enjoying the object, our interest or hobby becomes diseased, to the point of displaying alarmingly serious symptoms: the individual is prey to such convulsions that he/she is impelled to work far too much, in a hysterical way.

The result is the great worker, the person who was born to work and does not know how to do anything apart from work, according to his/her nearest and dearest.

Point two

It is not that there is anything wrong with the weekend supplements and

magazines. Their greatest attraction, so far as I am concerned, is that

unlike 90% of the newspaper in question they do not talk of politics, or

at least do not rub it in.

They put their finger on the spot when they talk about what we want to consume and guide us with comparisons and itineraries, even giving hotel breakfasts a mark from one to ten.

They teach us the universe we ought to know and none other. They give us the portion of information that makes up our average culture and makes us feel satisfied: now I know what I can buy from Monday on. I am sufficiently cultured to communicate with others around the dinner table without feeling excluded from any subject of conversation. I too can recite El País.

Point three

This is where an American appeared in Spain about fifteen years ago and

said: You have time but not a lot, and you need to see where that

microwave is cheapest without going all over town and laying yourself open

to getting towed away in seven different places or spending a fortune on

carparks. I have invented an artificial paradise for you where it is not

only warm in winter and cool in summer and you will not need an umbrella,

but you can forget about parking fines and all the shops that were

scattered all over town are under one roof fighting to death for your

custom.

This pretty tale of advantages and comfort was the birth of Commercial Centres in our country.

2. COMMERCIAL AREAS

When I was teaching project design and was trying to help the students to

understand an image or the simplified or symbolic essence of the project

being studied, I used to say that a market, the traditional market we find

all over the country, is basically a fountain with an umbrella. They could

see it close at hand at Tavernes Blanques market: in the afternoon, when

the stalls that were set up each day disappeared, all that was left was a

fountain for cleaning and a basic roof structure.

In the same way, if we add a refrigerator to this simplified set-up we have a supermarket, and if we add a parking space we have a hypermarket.

Because Europe is a land of markets, the French came up with the "Grande Surface", the "Large Surface" hypermarket or superstore. As well as a tap, an umbrella and a car space you get a trolley so you can buy more, so you can get your fill of shopping and give them lots more money. Very French.

But the American model was more attractive. It did not smell so much of food and what is more it managed to turn a wasteland into Madrid’s Calle Serrano, Valencia’s Calle Colón [or London’s Oxford Street]. So the French made the already Large Surface larger, to the point where people no longer knew what to do with the trolley. It got in the way among the carrots, shirts and hamburgers because, unblushingly competing with the real Commercial Centre, an increasingly complex gallery of assorted shops appeared next door to the hypermarket that was supposed to be the star attraction. It was as though the hypermarket that had developed the site was making more money by letting out shop space than by selling perishables.

The basic layout of a Commercial centre is one of the following:

A. Single motor (Department Store): the route

from the entrance to the Centre leads straight to the Department Store

B. Two motors: Poles at each end of the shopping street or mall, which has

entrances on either or both sides. This is the case of Nuevo Centro in

Valencia, which is unusual in having a single motor that has been

physically split in two to increase its attraction.

C. Various motors, usually four, located at each corner of a square. The

Commercial Centre accesses are on the sides of the square. This is the

layout of the Mall of America, which we will talk about later on.

To concentrate on our own geographical area, we have an excessive number of "commercial centres". Taking the American model as our reference, the quotation marks underline the big difference between these and a genuine Commercial Centre. The motor is different in the original and in the copy: in the former it is one or more department stores, basically devoted to fashion and household goods and furnishings (to use the traditional concepts that are beginning to be rather inadequate); in the latter food has been used to copy the motor, which in my opinion makes the mistake of combining the affliction/chore of buying daily food needs with leisure/fun buying.

The American model has grown by increasing in size, by incorporating a greater number of motors and accumulating many more shops under their wings. In other words, its growth has not signified any variation or degeneration of the original concept: everything is the same only bigger and more of it. One of the few Commercial Centres that answers to the original American model is Nuevo Centro, where I worked on the initial project and am now involved in its modernisation, fifteen years later.

3. COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE

Anyone who expects to create Architecture in capital letters when

designing a shopping centre is barking up the wrong tree. Commercial life

is a giddy whirl of change and it has a very clearly defined building code

that leads to a demand for ambience where little or no imagination is

required, insofar as the formal contribution of the architect is

concerned.

If we put the tap, the umbrella, the refrigerator, the car and the trolley in the cocktail shaker and shake them up with purely commercial criteria there is not much room left and it would be very dangerous to add any architectural ingredients to the cocktail; it probably cannot take much more than a cherry or a twist of lemon. We will see this more clearly and with less professional partiality if we look at how a street market springs up. Commercially it is perfect, they all are, and any attempt to arrange them or rationalise their spontaneity would be a mistake, it would be senseless.

A well-cooked paella does not require an architectural varnish. All that is needed to cook and eat it is a space, a table some chairs and little else. The exquisite design of a restaurant has nothing to do with the quality of the food.

In commercial terms, then, where the architectural setting is short-lived and changing and the yardstick is money, architecture reaches the highest peak of its service aspect. The buildings will probably not go down in the annals of Architecture, they are unlikely to have any other use in future and they will even end their days looking totally different from the original project in obedience to the law of commercial evolution. Raised to the status of spokesperson of the commercial sector, the most the architect can decide is where to put the tap and how big the umbrella is going to be, using an appropriate language (if he/she is being honest with him/herself and with others) so that the diverse and plural consumer will understand the layout and this, being easy to read, will contribute to the buying and selling process, to the maximum satisfaction of our customers, the retailers.

Far be it from me to question Rafael Moneo as a professional: I admire him both as a persona and as an architect. But there is nothing more unlike a commercial centre than his L’Illa project in Barcelona, to which third parties have given a prize. The question is: What criteria should prevail in the genesis of a commercial project in order to satisfy the retailers who are going to be setting up there, having attracted them in the first instance and subsequently, with the same project, the buyer-users who will keep the centre open and alive by being there? I believe that there are two very different sides to the answer to this question.

The first is based on the site and covers the reasons why the retailer is there, next to so-and-so and opposite such-and-such; these reasons are totally strategic and the architect has no voice in the matter.

The second is based on how the commercial landscape of the public areas is shaped, since those of each shop depend entirely on the retailer who acquires them, not on the author of the centre. We have to create an attractive, pleasant, legible and comfortable landscape, nothing more and nothing less. But I believe that this is the equivalent of choosing the right glass for the cocktail and putting in the cherry or, at most, the twist of lemon. The cocktail is mixed and drunk by others. Harsh but true.

4. EXAMPLES

As its name indicates, the Mall of America wants to be the biggest

Commercial Centre in the United States. With a surface area of one million

square metres it is only second in the whole world to that of Edmonton in

Canada, according to the latest Guiness Book of Records.

A million is a lot of square metres, so many that it is impossible to cover them all in one day, even walking fast. Using it is even more complicated, because as well as four very famous US department stores it has a large number of shops that are all over 1000 m2 as well as a casino, an aquarium with sharks that say hello and a kind of Disneyland fairground with all kinds of attractions of the type that make you scream, where the kids and some adults can have a great time while the rest of the family is spending like there’s no tomorrow.

Every possible space is under cover and the artificial atmosphere makes various millions of customers a year feel comfortable inside. A wise move is that the cars are housed in separate parking-only buildings, so they don’t become modules of anything but themselves. It’s magic.

The Mall is right next to Minneapolis-St. Paul airport. These Twin Cities are more like Siamese twins, joined or separated by the Mississipi. Their 4 million inhabitants are not, however, the Mall’s only source of customers.

The Mall of America draws its clientele from the rest of the state of Minnesota, where the next biggest town has a population of 100,000 and in many places it is perfectly possible to drive 50 or 100 miles without seeing any signs of human habitation.

The entire state, and neighbouring states too, use this Mall as often as we Valencians, for instance, go to the Nuevo Centro. The reason why it is sited right next to the airport is that the aeroplane is the most frequently-used means of transport to get to it.

So we are talking about a whole different retail dimension. Bigger, more on offer, wider catchment area, plus a complete range of services to satisfy kids or grandads, soldiers or civilians, single, married or living together, including a wild club scene and one of the biggest Planet Hollywoods in the world. Just like that, as if it you were setting up a sandwich bar.

Its influence and attraction are so great that the highest concentration of hotels in Minneapolis is around the Mall. People book a room, get on the plane and the whole family goes shopping for a few days. SPEC-TAC-U-LAR.

Then you have things like the shoe-shop being so big (1000 m2 and the same again in the store-room) that the shop assistant is wearing a headset and microphone to order no.43 up from the store rather than maybe missing a sale by going in person to get it. Or the Tom Cruise behind the bar serving 30 to 40 people on his own, with a smile, and nobody having the slightest cause for complaint. Like the sign in a New York shop window beside the first cordless telephone I saw, 20 years ago: Tomorrow what, America?

Minneapolis accepted that it snows heavily for 6 months a year, and decided it would be easier to move around on a higher level to avoid the ice. Like in Canadian cities such as Calgary, a covered passageway runs right through the centre of town and is heavily used. It has become a mall that people use to get from one place to another and where retailers have to go to sell anything. Historic precedents such as [London Bridge or] the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, or the puente de madera here in Valencia, the bridge from the trenet local railway station over to the Torres de Serranos [gateway to the city centre] which was covered in quiosks and stalls in the ‘40s and ‘50s, make it easy to understand how this pedestrian passageway should have become a retail trail.

The result is that vehicles move at street level but people have decided to move along the upper level, warm in winter and cool in summer with the added attraction of the commercial display – take a walk and look at the shop windows - so the retailers have brought all their artillery to bear on this level and it has turned into a jungle you need a machete to cut through because the offer is so overwhelming.

There are no shop windows at pavement level –

why would there be? The façade has moved up to the pedestrian

level and since it has not always been easy to push pedestrian streets

through the buildings, it is not unusual to have to go through the

menswear section of a department store to get to the lawyer or to a

concert. It is called Nicolet Mall.

…

Let’s get back to architecture. You can’t design a commercial centre without knowing about these precedents.

We had better think again if Mayordomo have more shoe-shops in Valencia than the Bancaja savings bank has branches. Something isn’t working if we are cutting up instead of uniting for strength.

We are getting back to the local shop, sorry, small enterprise, only they are in the new streets, in the commercial centres. In a city the size of Valencia there ought not to be more commercial centres than hospitals or secondary schools. There should be plenty of everything, but concentrating, bringing together and multiplying services.

To centre or centralise, commercially, means bringing all your efforts together in one place to improve your organisation and service. The thirty-seven shoe-shop managers should be the thirty-seven quality shop assistants in a great shop in a Great Commercial Centre.

This could be one of the aims of the architect, or of the specialised branch of architecture that is involved in the genesis of commercial centres, in the same way that the architect is involved in the way we inhabit. The commercial centre architect should not only decide on the colour and texture of the walls.

Hypermarkets are fine as markets. We eat three times a day and have to buy food frequently, almost every day. Taking advantage of this blinding glimpse of the obvious and placing shops along the path towards them, timidly at first and now exaggeratedly, the hypermarkets, playing at being commercial centres, have mushroomed wildly and we are beginning to have blown it. Seriously: Mayordomo also want to (and ought to) be there in the next one to open.