Luisa Fernández Rodríguez

Tutor/Supervisor:

Miguel del Rey Aymat

Rural Reminiscence in the Oporto School 1955-75, on the trail of Távora and Siza

Trabajo de Investigación/Research Paper

Mención COACV 2001-2002/Mention 2001-2002

Publicaciones, trabajos de investigación y tesis doctorales/

Publications, research and PhD Theses

| Elementos canónicos en arquitectura rural: Imágenes de la memoria rural en la escuela de Oporto, rastreando a Tavora y Siza |

|

|

| Autor/Author: Luisa Fernández Rodríguez Tutor/Supervisor: Miguel del Rey Aymat |

Canonical Elements in rural architecture: Rural Reminiscence in the Oporto School 1955-75, on the trail of Távora and Siza Trabajo de Investigación/Research Paper

|

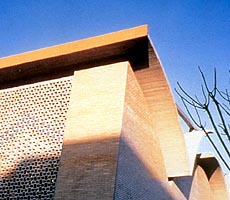

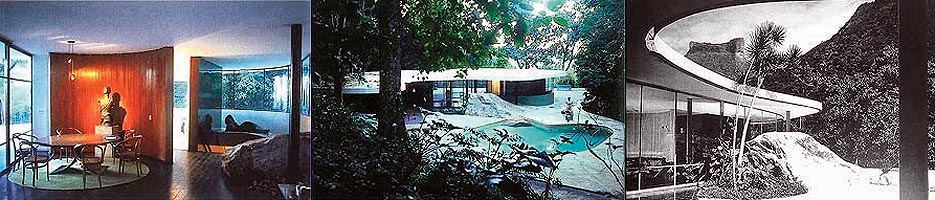

| Este trabajo de investigación se realiza tras unos cursos de doctorado y una reflexión posterior. Con un interés centrado en la capacidad de la Arquitectura Contemporánea para generar formas de expresión enraizadas, la investigación arranca sobre todo de las experiencias realizadas a lo largo del curso Iniciación a la arquitectura rural valenciana impartido por Juan Miguel del Rey, bajo cuya tutorización se elaboró este trabajo. A lo largo del mencionado curso se realizó una aproximación a la arquitectura rural y a la valenciana en particular, destacando los valores inalterables que permitían su clasificación y análisis tipológicos. Posteriormente se pasó a realizar un trabajo de campo en contacto directo con el medio rural, las pervivencias de la tradición vernácula y las problemáticas surgidas de la industrialización o el urbanismo insensibles con el entorno. La propuesta inspiradora de aprender a observar nuestro medio desde una nueva perspectiva investigadora con una óptica transformada a través de la lente fotográfica- puede considerarse como el origen primero de este intento de rastrear las posibilidades de supervivencia de las culturas populares propias a través de propuestas creativas y vitalistas. Tomando como referente este curso docente de los Estudios de Tercer Ciclo, se plantea el trabajo correspondiente al período de investigación. En su arranque, el trabajo aspiraba a ser una investigación general sobre la viabilidad de los modelos y mecanismos de la arquitectura vernácula en la arquitectura actual. Se buscó, como continuación de los cursos previos, la conexión entre ese hipotético tiempo pasado caracterizador de nuestras culturas y el momento en el que nos encontramos. Sin embargo demostrar esta continuidad no resultaba tan sencillo en el sentido TRADICIÓN - MODERNIDAD, por lo inabarcable del estudio sobre las tradiciones regionales. El trabajo sólo parecía viable adoptando el sentido opuesto, es decir aceptar que esa continuidad existe de hecho y así buscar las arquitecturas contemporáneas que desde las premisas de una modernidad crítica logran seguir construyendo la cultura regional propia. El trabajo final se estructura en dos partes diferenciadas: Una primera se centra en la llamada arquitectura regionalista y los diferentes modelos nacionales. La segunda parte desarrolla la arquitectura de la Escuela de Oporto en el intervalo 1955-1975, con referencia a la tradición cultural lusa. Se ha de recalcar que las arquitecturas regionalistas tienen en común un método inclusivo, abierto, no un estilo definido -aunque en ocasiones la fuerte caracterización cultural de sus realizaciones pueda llevar a pensar lo contrario- por lo que la osamenta principal de Imágenes de la Memoria Rural en la Escuela de Oporto, 1955-1975 podría aplicarse al caso brasileño, japonés, griego, español, etc. Todo el análisis, arquitectónico e histórico, pretende realizarse en gran medida desde la imagen con el soporte teórico preciso, respondiendo estrictamente al título Imágenes de la Memoria Rural en la Escuela de Oporto, 1955-1975. Rastreando a Távora y Siza. No se buscan imágenes con carga nostálgica, por lo contrario en el análisis de la arquitectura -ya sea popular o contemporánea- se sigue una metodología objetiva, señalando referencias u oposiciones pero rehuyendo, al menos esa es la intención, de cualquier contemplación añorante o pseudo-artística. La bibliografía empleada destaca por su heterogeneidad. La variedad de una tendencia arquitectónica que no pretende una clasificación excluyente sino abierta se refleja en la variada documentación manejada. En este punto tiene una presencia importante la obra teórica de Kenneth Frampton. A este respecto se señala la apropiación excesiva del término regionalista llevada a cabo por el crítico hasta elaborar una intrincada teoría que muestra en ocasiones una inflexibilidad y exigencia opuestas a la frescura propia de estas propuestas. . Los fundamentos sobre Arquitectura Rural se han extraído fundamentalmente del curso de doctorado de del Rey, Iniciación A La Arquitectura Rural Valenciana, y su bibliografía. A partir de ahí se realiza una aproximación al medio rural portugués, con influencia fundamental del Inquérito de Arquitectura Popular Portuguesa realizado parcialmente por el propio Távora. El material gráfico aportado en la introducción se ha extraído en su mayor parte de los monográficos de los arquitectos reseñados, mientras que en la segunda sección referida a la Arquitectura Portuguesa el material visual es propio en la medida de lo posible. En cuanto al tratamiento de la Arquitectura Rural Portuguesa se emplean fundamentalmente imágenes del Inquérito de 1956, por dos razones esenciales: ser fieles al material de campo manejado por Távora y su generación para la revitalización de una arquitectura moderna verdaderamente portuguesa y, en segundo lugar, por la progresiva degradación del medio rural. A. PRIMERA PARTE: ARQUITECTURA Y REGIONALISMO 1. La primera parte del trabajo consiste en la localización y análisis de arquitecturas regionales con energía suficiente como para impulsar su cultura regional además de representarla y por otra parte hacerlo desde el lado de la Arquitectura Moderna. La búsqueda de referencias se realiza a través de un proceso abierto. Así el método, al igual que las arquitecturas analizadas, es inclusivo, de manera que en cada ejemplo pueden descubrirse mecanismos y tratamientos similares, aun cuando los resultados difieran totalmente. En cualquier caso, se rechaza frontalmente cualquier nostalgia o recreación blanda de las arquitecturas comúnmente consideradas como tradicionales. Al rastrear los precedentes del regionalismo se intenta hacer evidente la flexibilidad de una clasificación no excluyente, que puede superponerse a muchas otras. Se incide sobre todo en la expansión de la modernidad a nivel global creando modalidades regionales, desde Wright al biorrealismo de raíz organicista de Neutra o Schlinder y sobre todo en la irrupción del realismo en el panorama europeo tras la debacle de la guerra que con manifestaciones singulares en Inglaterra o Italia, supone una nueva mirada hacia el hombre y su relación con la Historia y el entorno.

2. En este capítulo, el concepto de Regionalismo Crítico de Kenneth Frampton aparece inevitablemente como catalizador en el análisis de estas arquitecturas. En el trabajo se acepta el cuerpo central de la teoría sobre todo lo referente a la relación con el entorno, el clima, la topografía, la luz o su sugerente concepto de tectónica-, sin embargo se realiza una crítica a los aspectos más arbitrarios o subjetivos. La introducción del trabajo concluye con una revisión visual de las características generalizables de la Arquitectura Regionalista. Así se ejemplifican con amplia información gráfica los factores sensoriales y psicológicos latentes en la arquitectura del regionalismo, tan alejados de cualquier teoría escrita. Este muestrario un tanto anárquico pretende preparar visualmente al lector para la observación de una arquitectura donde los factores táctiles y experienciales van más allá de lo objetivo. |

This research was conducted following some PhD courses and a subsequent period of reflection. Stemming above all from the experiences gained during the Introduction to Valencian Rural Architecture course taught by Juan Miguel del Rey, who has kindly supervised this paper, its focus of interest is the ability of contemporary architecture to generate deep-rooted forms of expression. The course provided an introduction to rural architecture, particularly that of Valencia, underlining the unchanging values that enable it to be analysed typologically and classified. This led to field work in direct contact with the rural environment, the survival of vernacular traditions and the problems that have arisen as a result of an industrialisation or an urbanism that are insensitive towards their surroundings. The inspiring proposal that we should learn to observe our environs from a new research angle, with a viewpoint transformed by the lens of a camera, sowed the first seeds of this attempt to trace the possibilities of popular cultures surviving through lively, creative works. Taking this PhD course as a reference point, the working plan for the research stage was addressed. The study was initially intended to be a general investigation of the viability of the mechanisms and models of vernacular architecture in contemporary architecture. Following the courses previously taken, a connection was sought between the hypothetical past that gives our cultures their character and the moment in which we are living. However, it proved not to be so simple to demonstrate this continuity in the sense of TRADITIONAL - MODERN, as the study of regional traditions would have been too vast. The study only seemed to be viable from the opposite angle, in other words, by accepting that this continuity in fact exists and seeking the contemporary architectures that, while adopting the premises of critical modernism, manage to continue to build their own regional culture. The resulting paper is divided into two distinct parts: The first centres on what is known as regionalist architecture and its different national models. The second examines the architecture of the Oporto School during the 1955-1975 period, with reference to the Portuguese cultural tradition. It must be stressed that regionalist architectures share an open, inclusive method rather than a well-defined style (although at times the strong cultural characterisation of their works might suggest the contrary), so the framework of Images of Rural Reminiscence in the Oporto School, 1955-1975 could be applicable to Brazil, Japan, Greece, Spain, etc. The intention is to conduct the entire analysis, architectural and historical, largely through images, with the necessary technical underpinning, thus corresponding exactly to the subtitle, Images of Rural Reminiscence in the Oporto School 1955-75, on the trail of Távora and Siza. The aim is not to seek images charged with nostalgia. On the contrary, the examination of the architecture, whether popular or contemporary, follows an objective methodology, pointing out references or contrasts but intending, at least, to eschew any yearning or pseudo-artistic contemplation. The literature consulted is decidedly heterogeneous. The variety of an architectural tendency that aims for an open classification rather than one that excludes is reflected in the varied documentation employed. The theoretical work of Kenneth Frampton figures largely. In this respect, it must be pointed out that Frampton is excessive in his appropriation of the term 'regionalist', leading to an intricate theory that is at times demanding and inflexible, contrary to the innate freshness of these works. The fundamentals of rural architecture are taken, in essence, from del Rey's Iniciación A La Arquitectura Rural Valenciana PhD course and reading list. This is the starting point for an approach to the Portuguese rural environment that is largely influenced by the Inquérito de Arquitectura Popular Portuguesa, to which Távora himself contributed. The illustrations in the introduction are mostly taken from monographs on the architects mentioned in it, while in the second art, on Portuguese architecture, as far as possible they are the author's own. The discussion of Portuguese rural architecture mainly uses images from the 1956 Inquérito, for two basic reasons: firstly, faithfulness to the field materials used by Távora and his generation to revitalise a truly Portuguese modern architecture and, secondly, the progressive deterioration of the rural environment. A. PART ONE: ARCHITECTURE AND REGIONALISM 1.The first part of the study consisted in locating and examining regional architectures of sufficient energy to spur on the culture of their region and not only to represent it but also to do so from the point of view of Modernism. Reference points were sought through an open process. The method, like the architectures examined, is inclusive, so similar mechanisms and treatments can be found in each example even though the results are totally different. At all events, any nostalgic or bland recreation of the architectures commonly considered traditional is rejected utterly. When tracing the precursors of regionalism, an attempt is made to show the flexibility of a non-exclusive classification that can be superimposed on many others. Particular attention is paid to the world-wide expansion of modernism as it developed regional forms, from Wright to the bio-realism, rooted in organicism, of Neutra or Schindler and, above all, the realism that burst onto the European scene after the chaos of war. This, which took unusual forms in Britain or Italy, represented a new view of mankind and its relationship with history and its surroundings.

2. In this chapter, Kenneth Frampton's concept of Critical Regionalism inevitably makes its appearance, catalysing the examination of these architectures. 5.Having established the basis for the regionalism of the Oporto School, the final part examines the works and poetics of two contradictory but complementary figures: Távora and Siza. |

|

|