Le Corbusier. Views of Technique in Five Movements

|

Le Corbusier. Visiones de la técnica en

cinco tiempos

Le Corbusier. Views of Technique in Five Movements |

|

|

|

Jorge Torres Cueco |

| Premio

COACV 2003-2004/2003-2004 COACV Prize Publicaciones, Trabajos de Investigación y Tesis Doctorales/Publications, Research Papers and PHD Thesis

|

|||

| El objeto

del presente texto es proponer una lectura de la obra y pensamiento de Le

Corbusier en relación con el concepto de “técnica” en el sentido

más amplio del término y más allá de su condición práctica: sobre su

trascendencia al mundo de los significados. Sobre el papel que ha jugado

la técnica en la eclosión y continuidad de la arquitectura moderna han

debatido diversos autores, incluso desde posiciones contrapuestas. Tal es

el caso de Eric Hobsbawm, quien en A la zaga. Decadencia y fracaso de las

vanguardias del siglo XX mantenía que la arquitectura se ha salvado del

fracaso que han sufrido las vanguardias plásticas gracias a su

inseparable condición técnica. Por el contrario, Reyner Banham en

Teoría y diseño en la primera era de la máquina sostenía que la

arquitectura moderna fracasó “al no alcanzar el punto al que el

desarrollo de la tecnología podría haberle llevado”, y, así no llegó

a “materializar las promesas de la Era de la Máquina”.

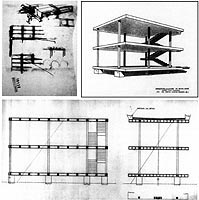

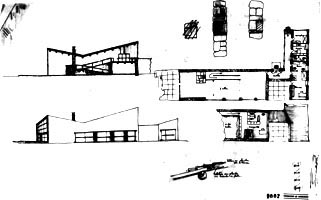

Para confrontar ambas posiciones tenemos a Le Corbusier como el arquitecto más relevante del siglo XX y que dejó más escritos y aparentemente más contradictorios al respecto. El texto se inicia con una introducción sobre la técnica y su papel en la arquitectura y se cierra con un anexo terminológico, para centrarse en su pensamiento técnico precedido de un capítulo sobre su formación. El concepto de técnica en Le Corbusier aparece poblado por los más ricos y diversos significados. Recorrió una trayectoria poliédrica en la que integró tendencias y aspiraciones dispares de lo que debía ser la arquitectura, la ciudad y la sociedad de su época. También fue uno de los arquitectos más fecundos en producir interrelaciones entre ideas e imágenes, disciplinas plásticas y arquitectura, entre historia y modernidad. En Le Corbusier este concepto aparece poblado por las más ricas y diversas acepciones. Por un lado, junto con la idea de “máquina” o “industria” parece un referente de su pensamiento; por otro, en su actividad profesional, en la práctica, es casi menospreciado. Es paradójica su fascinación por una técnica que no conocía, quizás por el hecho mismo de su desconocimiento. Pero nunca le prestó la debida atención práctica y de hecho, el libro está trufado por sus fracasos constructivos y tecnológicos. Sabemos que los pormenores técnicos -en algunos proyectos profusamente detallados (Cité de Refuge, Pabellón Suizo o Centrosoyuz)- fueron desarrollados principalmente por su primo y socio Pierre Jeanneret y más tarde aquellos ingenieros y arquitectos colaboradores de su estudio: André Wogensky, Iannis Xenaquis o Vladimir Bodiansky. No fue tampoco demasiado asiduo a las visitas y direcciones de obra. Y sin embargo una preocupación por la técnica como asunto conceptual -no empírico- recorrió su obra. Para comprender esta paradoja, se recurre a una construcción argumental, un andamio historiográfico o crítico: cinco series de proyectos enunciados en cinco tiempos bajo cinco pares de términos que nos pueden permitir diseccionar su pensamiento. Estos tiempos o pares de conceptos son: progreso e industria, máquina y purismo, tecnología y técnica, construcción y materia y tecnocracia e infraestructura. Es necesario indicar que estos cinco tiempos no responden necesariamente a un desarrollo cronológico. Son cinco pares de términos que unas veces se solapan, otras veces confluyen en distintos espacios cronológicos. El texto se inicia con una somera introducción sobre la técnica y su papel en la arquitectura y se cierra con un anexo terminológico, donde se trata de deslindar el significado o significados que comprenden los cinco vocablos que se utilizan en el curso del texto. Un capitulo preliminar dedicado a los TIEMPOS DE FORMACIÓN, recoge aquellos aspectos más sustanciales de su educación en relación a los contenidos e hipótesis que se desarrollan en el texto. En el PRIMER TIEMPO: EL IDEAL DEL PROGRESO, INDUSTRIA Y ARQUITECTURA, podemos seguir los primeros trabajos de Le Corbusier, en los que se revela como un “industrial” interesado más por la resolución del problema de la vivienda que por la definición de un nuevo lenguaje. Si éste surgía, sólo sería por mediación de los nuevos procedimientos industriales y la estandarización, La técnica, por tanto, aparece como la causa principal de la aparición o evolución de un estilo. Proyectos como las Cité ouvrière de Vouldy à Troyes (1919) La Manufacture Saint-Gobain en Thourotte (1920), Las Maisons ouvrières Grand-Couronne (1920) o la Maison ouvrière en série (1922) son concebidas y justificadas desde sus mismos procesos constructivos, y tienen en Les Quartiers moderns Frugès en Pessac (1924-27) su máxima expresión, donde Le Corbusier tuvo ocasión de experimentar con los procedimientos de construcción industrializada en un barrio completo. Esta vocación técnica y empresarial culminó en 1918 con la participación en la S.A.B.A. (Societé d’Application du Betón Armé), destinada a la promoción del hormigón armado, y en la creación de otra empresa asociada, la SEIE (Société d’enterprises industrielles et d’études), desde la que dirigió una pequeña fábrica de materiales de construcción en Alfortville, en la que trataba de experimentar con nuevos materiales, terminando en un sonado fracaso. Le Corbusier trataba de presentar la arquitectura como una disciplina autónoma regida por una legalidad intrínseca y que debía ser concertada con la industria, y permitiendo la presencia de valores arquitectónicos a priori. Con no pocos esfuerzos lograba unir así una tradición clásica e idealista - por el cual la arquitectura reside en principios eternos y leyes inmutables- con el positivismo francés y el historicismo alemán de corte hegeliano por el que el valor arquitectónico es relativo y dependiente del momento histórico. El SEGUNDO TIEMPO: EL IDEAL DE LA MAQUINA. PURISMO Y ARQUITECTURA, está dedicado a rastrear la analogía entre máquina, purismo y su arquitectura, perfectamente personificada en el automóvil. Lejos de las retóricas futuristas o las visiones mecanicistas del progreso, la máquina aparece como el modelo de un mundo artificial, pensado y realizado por el hombre, con su propia legalidad intrínseca, fruto de la precisión, del cálculo, del número, de la exclusión de lo superfluo, de la búsqueda de lo esencial a través de una selección mecánica. Sin embargo estas viviendas puristas son ajenas a los nuevos procedimientos constructivos. Son construidas con materiales tradicionales pero con una sintaxis nueva. No pretendía la modernización del clasicismo como en Garnier o Perret, sino proporcionar una nueva imagen técnica, maquinista, con fachadas tensas, ingrávidas y ligeras como las telas tensadas de los aviones o las planchas de acero de los automóviles o barcos. La fascinación por la técnica estará también presente en sus interiores: radiadores, instalaciones vistas, silenciosas carpinterías deslizantes, o las lámparas eléctricas desnudas: como en el garaje de la Villa Stein. Donde el coche es protagonista como en tantas otras fotografías donde sus proyectos son acompañados por su propia berlina 14CV de la marca Voisin, vehículo de los jóvenes intelectuales y artistas, reflejo de una forma de vivir moderna. Una vez más observamos su forma de operar fundamentalmente icónica. Las ideas se evocan a través de imágenes. Así había mostrado los grandes ejemplos del pasado. La tradición que había que recuperar, como ahora el espíritu de precisión, es mostrada a través de un conjunto de ejemplos concretos expresados a través de imágenes y dibujos. Su mirada era profundamente inquisitiva, y con una capacidad para sugerir nuevas cuestiones arquitectónicas. Por eso adquirieron tanta importancia sus dibujos de Pompeya, Roma o el Partenón alternados con aviones, silos o paquebotes: revelaban el escenario y prueba de verdad de su propia arquitectura. Por ello no importaba la incongruencia entre procedimientos artesanales e imágenes industriales en sus viviendas puristas: no hacía sino proponer el escenario de una técnica afín a los tiempos modernos, sin menoscabo des sus principios ideales que tenían una honda raíz en la historia. Sin embargo, había que trascender la mera reproducción de lo mecánico para manifestar que el mundo de la técnica respondía a la ciencia, la geometría y el número, es decir, a procesos puramente mentales. Y estos no son necesariamente contingentes, cambiantes e inestables, sino que se remiten a un orden profundo e inmutable análogo a un “mundo de las ideas” platónico que tan presente estuvo en sus años de formación. Estas ideas, indujeron este tipo de pensamiento en el que el arte era inseparable de la ciencia. Los principios están por delante de la técnica, y el NUMERO puede ser representado por una imagen -sólo imagen- técnica. En el TERCER TIEMPO: EL IDEAL DE LA TÉCNICA, TECNOLOGÍA Y ARQUITECTURA, observaremos su mayor radicalización a favor de una tecnología redentora, ejemplificadas en el “pan de verre”, el muro cortina y el “muro neutralizante” auxiliado por los modernos sistemas de climatización, ilustrados con la “respiration exàcte”. La cité de Refuge, el Pabellón Suizo y el Centrosoyuz, son los paradigmas de este momento, acompañados por una pléyade de proyectos en los que el vidrio asume un protagonismo inusitado. Todas estas fachadas puras y cristalinas no dejarán de producir una fuerte atracción en Le Corbusier, en la medida que envuelven formas y volúmenes puros, transparentan la realidad de la técnica que tras ellas se encierra, denotan directamente el espíritu de los tiempos modernos y gracias a la “respiration éxacte” adquieren el rango de lenguaje universal. Con estas obras se cierra un largo proceso en el que trató de conciliar la tecnología del momento con unos valores arquitectónicos que consideraba intemporales. Pero no sólo eso, sino que su confianza en la capacidad redentora, mesiánica, de la tecnología sobre la arquitectura y sus usuarios, iban a conducirle a los mayores riesgos estructurales y constructivos. La técnica es sublimada a idea pura, en la medida que permitía desarrollar unos conceptos y formas próximos a las bellezas esenciales del racionalismo clásico. La técnica, sinónimo de precisión, constituía algo más que una metáfora poética o una necesidad empírica, significaba en arquitectura la “identidad ontológica entre ciencia y arte”. La tecnología se aproximaba, según Alan Colquhoun, “a la condición de inmaterialidad” que presentaban sus inmensos paños de vidrio, tersos y puros. La arquitectura, como arte, no precisaba de signos convencionales y arbitrarios -órdenes clásicos, ornamentación o molduras- para emitir significado -una nueva sociedad-, sino que el significado era inmanente a las formas puras que las nuevas técnicas hacían posible. La tecnología en Le Corbusier se constituía en sí misma en imagen, símbolo e instrumento de la nueva sociedad y su arquitectura. En el CUARTO TIEMPO: EL IDEAL DE LA CONSTRUCCIÓN. ARQUITECTURA Y MATERIALES AMIGOS, podemos asistir a una aparente involución en la obra de Le Corbusier. Esta se daría en el entorno de los años treinta, influido por un regionalismo mediterráneo. Sin embargo, descubrimos que es capaz de alternar proyectos donde utiliza procedimientos constructivos arcaicos como la casa Errazuriz o la casa De Mandrot, con otros -algunos de ellos en colaboración con Jean Prouvé- donde se emplea una tecnología y una voluntad de tipificación propiamente modernas. En esta serie de proyectos no tiene ningún problema en emplear distintos niveles tecnológicos bajo un imperativo de precisión, armonía y economía social: no hay ninguna vocación ruralista, sino que simplemente asume un nuevo registro de materiales con los que operar con el mismo rigor y precisión que con los industriales. Así presenta las Maisons Murondins como un proceso constructivo que, si no es industrializado, exige una serie de operaciones rigurosas, precisas, con materiales que se han estandarizado, que se han realizado en serie, que se han calibrado para una perfecta ejecución. No hay diferencias en un orden conceptual, ni casi siquiera en el material -en cuanto a distinción entre naturales y artificiales, pues aquellos serán sometidos a un proceso mecánico, se mecanizan, se hacen artificiales- sólo existen unos materiales u otros puestos a disposición del constructor. Las diferencias radican en el acabado, en la precisión inherente a los propios materiales y no la precisión del proceso conceptual. La técnica ahora entendida en su sentido etimológico, como techné, no difiere en su esencia. El QUINTO TIEMPO: EL IDEAL DE LA INFRAESTRUCTURA. ARQUITECTURA TECNOCRACIA, versa sobre su espíritu tecnócrata y su acercamiento a la política a través de sus contactos con el movimiento Le Redressement français, grupo de sindicalistas moderados e intelectuales de centro derecha como François de Pierrefeu. Es desde el poder como se podría producir la implantación de la arquitectura moderna. En estos momentos propone nuevas infraestructuras habitables encargadas por el estado, capaces de renovar la producción arquitectónica y la sociedad, como los planos de Argel, Montevideo o Sao Paolo. Tuvo que esperar una década para obtener un importante apoyo de la administración con la Cité radieuse de Marsella: su primera Unité d’habitacion. Una visión de este proyecto permite comprobar la imposibilidad de la perfección moderna, para así asumir la tosquedad como un valor estético a explorar, bajo la precisión que el nuevo sistema antropométrico, el Modulor, impondría en el propio diseño. Con l’Unité, más allá de la apología de la producción industrial regida por un pensamiento tecnocrático, surgía con contundencia una reflexión, iniciada años antes, sobre la técnica y la arquitectura. El “brutalismo” conferido a la imagen del edificio no hacía sino testimoniar las condiciones de producción y construcción del proyecto. La quimera tecnológica no podía conducir a una imagen discordante con la realidad del producto y su pertinencia social. Hay una elección “moral” que va contra la misma idea de “novedad”, utiliza de modo didáctico técnicas y materiales que se oponen al “gesto mecánico” de la producción habitual. La obra siguiente de Le Corbusier estará caracterizada por esta visión amplia y, a su vez, consciente de la realidad artística y técnica de la arquitectura. No hay rastros de ningún determinismo mecanicista, sino que la técnica es poliédrica como lo es la realidad a la que sirve. Basta observar los distintos volúmenes de su Oeuvre complète para percatarse de la versatilidad con que resuelve los distintos encargos. La expresiva Notre-Dame-du-Haut de Ronchamp, saturada de sugestiones místicas; el brutalismo del Convento de la Tourette -probablemente una de sus obras más conseguidas-, con sus evocaciones a las estructuras cirstencienses; los diversos proyectos para Chandigarh, con todas su simbologías cósmicas; el Visual Arts Center en Cambridge, como una reconsideración de obras anteriores; la Maison du Brésil en la Ciudad Universitaria de París; el Pavillon Philips en Bruselas, un alarde de la técnica donde petrifica una lona con prefabricados de hormigón y cables tensados; o el Pabellón de exposición en Zurich, donde reaparece la pulcritud de unos paraguas metálicos que protegen un volumen encerrado por brillantes paneles coloreados de porcelana esmaltada y lunas de vídrio, todos ellos muestran una decidida opción por una pertinencia técnica para cada situación concreta. EPÍLOGO Pero si hay algo que realmente se configura como hilo conductor de su pensamiento es la idea de precisión que debe ser inherente al concepto de técnica en su sentido más amplio, como techné, que en el mundo griego designaba la habilidad manual mediante la cual se transforma una realidad natural por otra artificial. Que exigía unas reglas, talento, intuición y destreza. La inicial precisión exigida a la máquina o a la tecnología se encontraba en las mismas raíces de la arquitectura, desde entonces, la técnica debía ser, sin más, pertinente. Al final, el compromiso con la técnica era, también, un compromiso artístico y social. Es cierto que su concepción tecnocrática y su visión de la arquitectura casi como un medio de ingeniería social, mesiánica y redentorista, ha caído en descrédito. Son evidentes sus contradicciones y los fracasos “técnicos” que cosechó no así su arquitectura que salió triunfante. Como dice Alan Colquhoum, sus equivocaciones fueron las propias de un artista-filósofo para quien la arquitectura, precisamente por el vínculo que establece entre el ideal y la realidad, era la más profunda de las verdades. |

This text proposes a reading of the works and thinking of Le Corbusier in relation to the concept of ‘technique’, in the widest sense of the term, over and above its practical nature: on its transcendence into the world of meanings. The rôle of technique in the birth and continuity of modern architecture has been debated by a number of authors, even from opposing points of view. Eric Hobsbawm is one. In Behind the Times: The Decline and Fall of the Twentieth Century Avant-Gardes, he maintained that architecture escaped the downfall of the art avant-gardes thanks to its inherently technical nature. Reyner Banham, on the other hand, sustained in Theory and Design in the First Machine Age that modern architecture failed in not going as far as the development of technology could have taken it and therefore not materialising the promises of the Machine Age. To confront both points of view, we have Le Corbusier, the most important architect of the 20th century and the one who left the greatest number, and apparently the most contradictory, of writings on the subject. This text begins with an introduction to technique and its rôle in architecture and ends with a terminology appendix. In between, after a chapter on Le Corbusier’s training, it focuses on his thoughts on technical matters. His concept of technique appears to cover a great richness and variety of meanings. In his many-sided career, he incorporated disparate tendencies and aspirations concerning what the architecture, the city and the society of his day should be. He was also one of the most fertile of architects in interrelating ideas and images, the arts and architecture, history and modernity. In Le Corbusier, the concept of technique is populated with the richest and most diverse meanings. On the one hand, the idea of ‘machine’ or ‘industry’ seems to be one of his reference points; on the other, in his professional life, in practice, it is almost scorned. His fascination with a technique he did not know is paradoxical; it may be due to his very ignorance. However, he never paid it due practical attention and the book is full of his construction and technological failures. We know that the technical details (profusely detailed in some projects, such as Cité de Refuge, the Swiss Pavilion or Centrosoyuz) were mainly worked out by his cousin and partner Pierre Jeanneret and, later, by engineers and architects who worked in his studio: André Wogensky, Iannis Xenakis or Vladimir Bodiansky. Neither was he particularly assiduous in visiting and supervising the building works. Nonetheless, a concern with technique, as a conceptual rather than an empirical matter, runs throughout his work. To understand this paradox, I resorted to a guiding construct, a historical or critical framework: five series of projects formulated in five times or movements headed by five pairs of terms that help to dissect his thinking. These movements or pairs of concepts are: progress and industry, machine and purism, technology and technique, construction and matter, technocracy and infrastructure. It should be mentioned that they do not necessarily reflect a chronological development. They are five pairs of terms that sometimes overlap and at other times mingle in different chronological spaces. The book begins with a brief introduction to technique and its rôle in architecture and ends with a terminology appendix that attempts to make a distinction between the meaning or meanings covered by the five sets of words. A preliminary chapter on his FORMATIVE YEARS looks at the most fundamental aspects of his education in relation to the contents and hypotheses set out in this book. The FIRST MOVEMENT: THE IDEAL OF PROGRESS, INDUSTRY AND ARCHITECTURE follows his early work, where he is revealed as an ‘industrialist’, more interested in solving the housing problem than in defining a new language. If this arose, it would only be through the agency of new industrial procedures and standardisation. Technique, therefore, is the main reason for the appearance or evolution of a style. Projects such as the Cité Ouvrière du Vouldy in Troyes (1919), the Manufacture Saint-Gobain in Thourotte (1920), the Maisons Ouvrières Grand-Couronne (1920) or the Maison Ouvrière en série (1922) were conceived through and justified by their construction procedures. The maximum expression of this is the Quartiers Moderns Frugès in Pessac (1924-27), where he had the chance to experiment with industrial construction methods in an entire neighbourhood. This technical and commercial vocation culminated in 1918 with his partnership in S.A.B.A. (Societé d’Application du Betón Armé), a company that promoted reinforced concrete, and the founding of an associated company, SEIE (Société d’enterprises industrielles et d’études), in which he managed a small building materials factory in Alfortville where he tried to experiment with new materials, ending in complete failure. Le Corbusier tried to present architecture as an autonomous discipline governed by an intrinsic law that should be agreed with industry, allowing architectural values to be present a priori. Not without considerable effort, he thus managed to unite a classical and idealist tradition, in which architecture resides in eternal principles and immutable laws, with French positivism and a Hegelian-style German historicism in which architectural value is relative and depends on the moment in history. The SECOND MOVEMENT: THE MACHINE IDEAL. PURISM AND ARCHITECTURE traces the analogy between machine, purism and architecture, with the car as its perfect personification. Far from futurist rhetoric or mechanicist visions of progress, the machine is the model of an artificial world, designed and constructed by man. It has its own intrinsic law, the result of precision, calculation, numbers, the exclusion of superfluity, a search for the essence through mechanical selection. These purist houses have nothing in common with the new construction procedures, however. They are made of traditional materials, although with a new syntax. He was not aiming to modernise classicism, like Garnier or Perret, but to present a new technical, machinist image, with taut, light, weightless façades like the stretched fabrics covering aeroplanes or the sheet steel of cars and ships. His fascination for technical matters is also visible in his interiors: radiators, exposed pipes, silently sliding joinery or bare electric bulbs, as in the Villa Stein garage. Here the car is the star, as in so many other photographs where his projects are accompanied by his own Voisin 14 HP berlin, the car of young intellectuals and artists, reflecting a modern lifestyle. Once again we find a fundamentally iconic modus operandi. Ideas are evoked by images. That is how he had shown the great examples of the past. The tradition to be recovered, such as the spirit of precision, is shown through a set of specific examples expressed in images and drawings. He had a deeply inquisitive eye, with a capacity for suggesting new architectural issues. That is why his drawings of Pompeii, Rome or the Parthenon, alternating with aeroplanes, silos or ships, became so important: they revealed the setting and true demonstration of his own architecture. For this reason, the incongruent juxtaposition of craft methods and industrial images in his purist houses did not matter: he was only proposing a setting for a technique in keeping with modern times, without detriment to his ideal principles, deeply rooted in history. However, the mere production of mechanical things had to be transcended to show that the technical world was that of science, geometry and number, in other words, of purely mental processes. And these are not necessarily contingent, changing and unstable: they refer to a deep, immutable order, analogous to a Platonic ‘world of ideas’ that was very much part of his formative years. These ideas induced this frame of thought in which art was inseparable from science. Principles come before technique, and NUMBER can be represented by a technical image - an image only. In the THIRD MOVEMENT: THE IDEAL OF TECHNIQUE, TECHNOLOGY AND ARCHITECTURE we find his most radical favouring of a redemptive technology exemplified by the ‘pan de verre’, the curtain wall and the ‘neutralising wall’ assisted by modern climate control systems, illustrated by the ‘respiration exacte’. The Cité de Refuge, Swiss Pavilion and Centrosoyuz are the paradigms of this moment, accompanied by a cluster of projects in which glass is featured with unusual prominence. All these pure, crystalline façades held a great attraction for Le Corbusier, insofar as they envelop pure forms and volumes, allow the reality of the technique that lies behind them to show through, directly denote the spirit of modern times and, thanks to ‘respiration exacte’, rise to the level of a universal language. These works brought to a close a long process in which he was trying to reconcile the technology of the time with architectural values that he considered timeless. But this was not all: his confidence in the messianic power of technology to redeem architecture and its users were to lead him to take enormous structural and constructive risks. Technique was sublimated into pure idea, insofar as it allowed him to develop concepts and forms that approached the essential beauties of classical rationalism. Technique, a synonym of precision, was more than just a poetic metaphor or an empirical necessity: in architecture, it signified the “ontological identity between science and art”. According to Alan Colquhoun, technology came close to the “condition of immateriality” presented by his immense, terse and pure stretches of glass. Architecture, as art, did not require conventional, arbitrary signs (classical orders, ornament or mouldings) to convey meaning (a new society): the meaning was immanent in the pure forms made possible by the new techniques. In Le Corbusier, technology in itself constituted an image, symbol and instrument of the new society and its architecture. In the FOURTH MOVEMENT: THE IDEAL OF CONSTRUCTION. ARCHITECTURE AND FRIENDLY MATERIALS we witness an apparent regression in Le Corbusier’s work. This took place around the 1930s, influenced by Mediterranean regionalism. However, what we discover is that he was capable of alternating projects that used archaic building methods, such as the Errazuriz house or the De Mandrot house, with others (some with Jean Prouvé) that employed a technology and a desire to typify that are strictly modern. In this series of projects he had no objection to using different levels of technology, subsumed under the imperative of precision, harmony and social economy: this was no ruralist inclination, merely a new register of materials with which to operate with the same rigour and precision as with industrial ones. The Maisons Murondins were thus presented as a construction process which, while not industrialised, demanded a series of rigorous, precise operations with materials that had been standardised, mass produced and sized for perfect execution. There were no differences at a conceptual level, nor practically any at a material level in terms of a distinction between natural and artificial, as the natural ones were subjected to a mechanical process, mechanised, made artificial, there were just certain materials or others for the builder to use. The differences lie in the finish, in the inherent precision of the materials themselves rather than the precision of the conceptual process. The technique, understood here in its etymological sense as techné, does not differ in its essence. The FIFTH MOVEMENT: THE IDEAL Of INFRASTRUCTURE. ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOCRACY deals with his technocratic spirit and his involvement with politics through his contact with the Redressement Français movement, a group of moderate trade unionists and centre-right intellectuals such as François de Pierrefeu. From a position of power, modern architecture could be introduced. During that time he proposed new habitable infrastructures commissioned by the state that could renew architectural production and society, such as his plans for Algiers, Montevideo or Sao Paolo. He had to wait a decade to obtain serious government backing for the Cité Radieuse, in the form of his first Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles. Seeing this project provides proof of the impossibility of modern perfection and hence an acceptance of roughness as an aesthetic value to be explored, subject to the precision that the new anthropometric system, the Modulor, would impose on the design. With the Unité, over and beyond an apologia for industrial production governed by technocratic thinking, a reflection on technique and architecture that had begun years previously came strongly to the fore. The ‘brutalism’ of the building’s appearance merely bore witness to the project’s production and construction conditions. The technological chimera could not give rise to an image that clashed with the reality of the project and its social pertinance. There is a ‘moral’ choice that works against the very idea of ‘novelty’; he made a didactic use of techniques and materials that are opposed to the ‘mechanical gesture’ of normal production. Le Corbusier’s subsequent work was characterised by this breadth of vision accompanied by an awareness of the artistic and technical reality of architecture. There is no trace of any mechanicist determinism; technique is many-sided, as is the reality it serves. One need only leaf through the various volumes of the Oeuvre complète to realise how versatile were his solutions to different commissions. The expressive Notre-Dame-du-Haut at Ronchamp, saturated with suggestions of mysticism, the brutalism of La Tourette monastery (probably one of his most accomplished works) with its evocations of Cistercian structures, the various projects for Chandigarh, with their cosmic symbolism, the Visual Arts Center in Cambridge, like a reconsideration of earlier works, the Maison du Brésil for the Cité Universitaire in Paris, the Philips Pavilion in Brussels, a technical tour-de-force where he petrified a tent with prefabricated concrete and taut cables, or the Zurich Exhibition pavilion, where the pulchritude of metal umbrellas reappears, protecting a space enclosed by gleaming coloured panels of enamelled porcelain and glazed windows: all these demonstrate a clear choice of technical pertinence to each specific situation. EPILOGUE If there is any real thread that runs throughout his thinking, however, that is the idea that precision must be inherent to the concept of technique in its widest sense, as techné, which in the Greek world meant the manual skill by which a natural reality is transformed into an artificial reality. This demands rules, talent, intuition and dexterity. The initial precision demanded of the machine or of technology was to be found in the very roots of architecture; thereafter, technique must be simply pertinent. When all is said and done, his commitment to technique was also an artistic and social commitment. Certainly, his technocratic concept and his vision of architecture, almost as a means of social engineering, messianic and redemptive, has fallen into discredit. His contradictions and his ‘technical’ failures are evident, but his architecture emerges triumphant. As Alan Colquhoum said, his mistakes were those of an artist/philosopher for whom architecture, precisely because it establishes a link between the ideal and the reality, was the deepest of all truths. |

|

|

|

|

|