|

Algunos comentarios en torno a

la obra de Vicente Valls

Las siguientes observaciones,

que tal vez no sean más que meros apuntes, intentan y permiten una

reflexión de carácter más general tomando como excusa la obra del

arquitecto valenciano Vicente Valls, a quien el Colegio Oficial de

Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana acaba de conceder el título de

Mestre d’Arquitectura. Esta distinción que, anualmente, otorga este

Colegio de Arquitectos como reconocimiento a una trayectoria profesional,

deja a un lado la atención hacia una realización concreta y pretende

poner en valor el conjunto de una serie de obras ejemplares que el paso

del tiempo ha tornado “anónimas”, haciendo que las apreciemos más

por lo que en realidad son que por la persona que las proyectó. En este

proceso, el tiempo ha ido matizando la presencia y significación de los

edificios en la ciudad; en la misma medida en que ha ido haciendo caer en

el olvido -más o menos injustamente- a los autores de las mismas. Bien

esta que así sea, pues es necesario acabar con la idolatría,

especialmente en una época como la nuestra en la que el culto al nombre

propio distorsiona la percepción de la obra, hasta el punto de anular

cualquier visión crítica que permita comprender el verdadero alcance de

las cosas.

Al revisar fotografías de

edificios de Vicente Valls, descubro al autor de gran cantidad de obras

que, al pasear por las calles de la ciudad de Valencia, siempre había

apreciado por el grado de sencillez y verdad con el que resolvían

problemas urbanos o arquitectónicos y porque mostraban claramente la

creencia del profesional que estaba detrás en el trabajo que se

realizaba; sabiendo además que su responsable, ciertamente, debía ser un

gran arquitecto, aunque desconociera su nombre. Es posible que ahora, al

publicar estas imágenes, otras personas experimenten la misma sensación

que yo trato de describir y que también asocien por fin el nombre de

Vicente Valls con unas estupendas realizaciones, haciendo que en su

memoria perviva ya un vínculo obra-autor, cuya unión había desdibujado

el tiempo.

La arquitectura de Vicente

Valls trasluce una serie de actitudes que evidencian la creencia en los

postulados de la modernidad como conceptos que retraen a un concepto más

amplio: el de “civilización”. Y está la voluntad individual, el

empeño silencioso por asumir en nuestra cultura y en el contexto

particular de nuestras latitudes la civilización moderna que estaba

transformando Europa desde principios del siglo XX, pero que el trauma de

la Guerra Civil había alejado de nuestro país.

Tal vez sea ésta la idea que

más desearía resaltar, la creencia y la fe en que tan solo desde el

rigor que caracterizó la generación de Valls puede haber futuro para las

ciudades y para la arquitectura. Pues frente al culto a la individualidad,

el culto a la civilización desarrollada por individuos concretos en

lugares específicos.

Sólo resta contemplar en

silencio estas imágenes y reflexionar sobre ellas, aprender de sus

soluciones y seguir evolucionado, mas allá de las circunstancias.

Carlos Meri Cucart |

A

few remarks on the work of Vicente Valls

The work of Vicente Valls, the Valencian architect

who was recently awarded the title of Mestre d’Arquitectura by the

Official College of Architects of the Valencian Community, provides an

excuse for the following comments, or perhaps merely notes, which attempt,

and allow, a more general reflection. The distinction for lifetime

achievement which this College of Architects awards annually turns aside

from the attention paid to particular buildings, as it aims to draw

attention to the value of an entire series of exemplary works that have

become ‘anonymous’ with the passage of time, making us appreciate them

more for what they really are than for the person who designed them. Time,

in this process, has toned down the visibility and significance of the

buildings in the city, to the same extent that it has gradually led their

architects to be forgotten, more or less unjustly. This is all to the

good, as we need to do away with idolatry, particularly in an age such as

ours when the cult of big names distorts the perception of the work to the

point of destroying any critical view that would allow the true scope of

things to be understood.

While looking through photographs of buildings by

Vicente Valls, I have discovered the creator of a great number of works

which, as I walked around Valencia, I had always appreciated because of

the degree of simplicity and truth with which urban or architectural

problems had been solved and because they obviously showed that the

architect behind them believed in the work he was doing; I had also known

that although I did not know his name, whoever was responsible for them

was certainly a great architect The publication of these images may

perhaps now give other people the same feeling as I have attempted to

describe and they too may finally associate the name of Vicente Valls with

some superb buildings, so that the link between the work and the architect

that had become blurred by time lives on in their memory.

The architecture of Vicente Valls reveals a series

of attitudes that show his belief in the postulates of the Modern Movement

as concepts that lead back to a wider concept, that of ‘civilisation’.

There is also the individual willpower, the silent determination, in the

particular context of this land and its culture, to adopt the modern

civilisation that had been transforming Europe since the early 20th

century but had been banished from Spain by the trauma of the Civil War.

This idea that I would like to emphasise most,

perhaps, is his belief and faith that only through the rigour that

characterised his generation could there be a future for cities and for

architecture. Rather than the cult of individuals, therefore, this means

the cult of a civilisation developed by specific people in specific

places.

All that remains to be done is to contemplate these

images in silence and reflect on them, learn from their solutions and

continue to develop, rising above circumstances.

Carlos Meri Cucart |

|

|

Vicente Valls, que a sus 81 años ha recibido del

Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana la distinción

de Mestre Valencià d’Arquitectura, como reconocimiento al conjunto de

su obra, es natural de Alcoy, donde nació en 1924. Estudió la carrera de

Arquitectura en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid y

obtuvo el título en 1951 alcanzando en 1965 el grado de Doctor

Arquitecto. Sin embargo y aunque realizó una breve incursión en el

ámbito de la de la docencia universitaria cuando, durante el curso

1969-70 impartió clases de Construcción II en la Escuela de Arquitectura

de Valencia, su vida ha estado esencialmente vinculada al ejercicio libre

de la profesión. El gran número y la calidad de sus obras proyectadas y

construidas avalan la solvencia de una trayectoria que él mismo sólo

quiere definir como una vida de dedicación, exigencia y trabajo para

ofrecer a su cliente el mayor rigor en las soluciones aportadas.

En efecto, Vicente Valls es, ante todo, un

arquitecto de oficio forjado en la responsabilidad. Siendo estudiante de

arquitectura, ante la irremediable enfermedad de su padre, el también

arquitecto Vicente Valls Gadea y con la comprometida situación familiar

de ser el mayor de nueve hermanos, se vio en la obligación de adelantar

dos cursos por año para sin tiempo que perder, ocuparse del estudio,

encargos y clientes de su padre. Inició de esta forma, tan abrupta y

difícil, su carrera profesional en 1951, dirigiendo las obras ya en curso

de varios edificios de viviendas.

Ese mismo año accedió por oposición al

cargo de arquitecto del Instituto de Colonización, obteniendo el número

uno, pero por motivos familiares tuvo que renunciar a la plaza. En 1953,

también por oposición, se convirtió en arquitecto al servicio de la

Hacienda Pública, siendo destinado primeramente a Albacete (1954-57) y

más tarde a Valencia, hasta que solicitó la excedencia en 1961 para

poder hacer frente a su labor como arquitecto de la Obra Sindical del

Hogar (OSH) ya que en 1957, precisamente el año de la Riada del Turia,

había sido nombrado funcionario de dicha institución para la que

proyectó y construyó soluciones de urgencia materializadas en los

importantes grupos de viviendas sociales por los que principalmente es

conocido.

En esa misma época sustituye a su padre

-que además era arquitecto municipal de Valencia- en la Compañía de

Tranvías y dirige algunos grupos escolares, a la par que proyecta

diversos conjuntos de viviendas para cooperativas de obreros, como las de

Tabernes Blanques, Chelva, o el Grupo San Rafael en Buñol, encargado por

la Compañía Valenciana de Cementos.

Paralelamente, en el campo de la promoción

privada dirige en Valencia la obra para Gerardo Bacharach del bloque de

viviendas del chaflán Cirilo Amorós e Isabel la Católica (1956-57) que

había proyectado Luis Gutiérrez Soto. En este caso, Vicente Valls -que

sólo se reunió con el conocido arquitecto en las tres ocasiones éste

que visitó la obra- se hizo cargo de toda la materialización del

proyecto y a él se debe el cuidado y expresivo despiece de ladrillo que

caracteriza la imagen del edificio.

Entre los importantes trabajos de

arquitectura y planificación urbanística realizados para la

Administración entre los años 50 y 70 y, generalmente, llevados a cabo

en colaboración con otros arquitectos también funcionarios, destacan el

Grupo de viviendas “Vicente Mortes” (1972-74), en colaboración con

García Sanz y Mensua, de 1200 viviendas, en el Polígono Fonteta de San

Luis, avenida Hermanos Maristas de Valencia; el Grupo “Virgen de los

Desamparados” (1954-62) de la Avenida del Cid, también en Valencia

junto con Costa, Cabrero y Tatay; o las 1800 viviendas del Barrio de la

Paz, en el Polígono Vistabella (1960-62) en Murcia. Publicadas en la

revista Hogar y Arquitectura y, actualmente, objeto de una controversia

entre vecinos, Ayuntamiento y promoción privada, cuya disputa ha

suscitado dos bandos enfrentados, uno, a favor de su demolición y

posterior especulación con el suelo y, otro, decidido a conservar y

rehabilitar este conjunto de notables valores arquitectónicos, excelente

implantación urbana y gran calidad ambiental, fruto de una reflexión

sobre ciudad, espacios públicos, zonas verdes y vivienda social que aún

hoy sorprende por su insólita vigencia.

Por supuesto, dentro de este mismo ámbito

de la residencia colectiva promovida por los poderes públicos se debe

subrayar la relevancia del Grupo de 1000 viviendas “Antonio Rueda”,

(1969-72), una obra ya sin titubeos, realizada en colaboración con los

arquitectos García Sanz y Marés, en la avenida de Tres Forques en

Valencia.

Construido en las etapas finales de las

conocidas iniciativas de alojamientos sociales y de políticas

viviendísticas de los sucesivos gobiernos franquistas desde la posguerra

a los años 70, la experiencia del Grupo “Antonio Rueda” pone de

manifiesto la importancia y la necesidad de realizar una arquitectura de

calidad a partir de las restricciones impuestas por una férrea normativa

oficial que, en este caso, es meticulosamente cumplida hasta la última de

sus puntualizaciones.

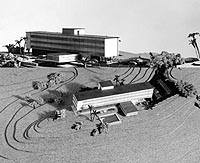

Esta gran operación residencial, también

vinculada al desaparecido organismo de la Obra Sindical del Hogar, supone

la construcción de un polígono de 1002 viviendas subvencionadas en

régimen de Renta Limitada. El complejo se asienta sobre un terreno de

considerable superficie ubicado en la periferia de la ciudad de Valencia,

un ámbito geográfico y social que, en aquellos años, se estaba poblando

a través de numerosas promociones estatales que canalizaban la

emigración del campo a la ciudad y, por supuesto y aún en esa fecha,

continuaban realojando a los damnificados de las dramáticas inundaciones

del río Turia.

El trasfondo de todas estas iniciativas de

vivienda social no es difícil de rastrear. Los postulados modernos

habían sido ya plenamente asumidos por una generación de arquitectos que

también había asistido a la construcción los Poblados Dirigidos de

Madrid, Castilla y Andalucía, terminados hacía relativamente poco tiempo

y ya ocupados. De hecho, se pueden apreciar incluso ciertos paralelismos

en la organización en torno a espacios públicos y edificios dotacionales

de los bloques que configuran el conjunto de “Antonio Rueda” con los

de “Caño Roto” (1957-59) de Iñiguez Onzoño y Vázquez de Castro.

También el resultado formal del Grupo “Antonio Rueda” parece deudor

del Poblado madrileño, al incorporar elementos constructivos a los que

confía una imagen final de claros ecos racionalistas.

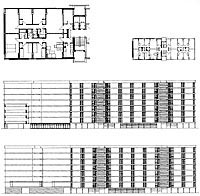

Ahora bien, en el caso de las viviendas de

Valencia, la ordenación urbanística se plantea desde otros supuestos

-nada tienen que ver las condiciones topográficas y ambientales- y ésta

fundamentalmente queda articulada sobre la base organizativa de módulos

vecinales de unas 200 viviendas en torno a espacios públicos, a los que

el arquitecto denomina unidades cívicas. Dichos módulos son repetidos

sucesivamente, definiendo la estructura del conjunto, que resuelve su

implantación urbana a través de un mecanismo de adición y facilita la

lectura global de la intervención. Pero a su vez la estrategia planteada

es lo suficientemente flexible para asumir y adaptarse a las

irregularidades geométricas de cada unidad o del solar en su conjunto.

De modo similar a como procedía en el

proyecto para el citado Polígono de Vistabella en Murcia, en el Grupo “Antonio

Rueda”, Vicente Valls recurre al vaciado estratégico de zonas

ajardinadas de uso vecinal y público que amplifican la calidad ambiental

y redundan en la cualidad urbana de la arquitectura planteada. Ahora

también, en el caso del conjunto de Tres Forques los arquitectos realizan

una previsión para hipotéticos equipamientos colectivos que, más tarde,

sirvieron de manera efectiva como base para la construcción real de

infraestructuras educativas. Dicha previsión, en última instancia

incidía sobre la volumetría de cada unidad, que termina siendo

conformada por dos bloques paralelos de ocho plantas, otro perpendicular

de cuatro donde se localizan los bajos comerciales y una plataforma de

conexión que recoge viviendas unifamiliares en dúplex -de nuevo se toman

decisiones que remiten a “Caño Roto”. Completan el conjunto dos

torres de doce plantas situadas en los extremos.

El propio Vicente Valls, al referirse al

Grupo “Antonio Rueda”, afirma que ante las limitaciones impuestas por

los mínimos presupuestarios 1 y la estricta normativa que definía hasta

dimensiones específicas para cada estancia, distribuciones, geometrías,

posiciones de mobiliario e independencias, los esfuerzos de su equipo de

arquitectos tuvieron que concentrarse fundamentalmente en la

planificación de los espacios libres y la implantación de los bloques

-para los que la norma sí permitía una mayor libertad- que se trató de

aprovechar proyectando lugares de relación que facilitaran la convivencia

y el disfrute de los futuros usuarios de las viviendas. Huyendo así de

cualquier referencia conceptual directa al proyecto moderno, Vicente Valls

expone sencillamente que su trabajo en realidad se limitó a crear

auténticos espacios de relación, convencido de que el adecuado

soleamiento, los jardines y el arbolado posibilitarían un lugar mejor y

un ambiente más humano que los vecinos sentirían como propio. Esta

actitud revela de nuevo al mejor Valls, el arquitecto de oficio que, como

muchos otros auténticos profesionales en aquellos años, habiendo asumido

-incluso, tal vez podría decirse que de manera inconsciente- los

postulados modernos, tanto contribuyeron al progreso 2 de la arquitectura

porque su trabajo, alejado de cualquier innovación gratuita simplemente

pretendía resolver de manera inteligente los problemas que se planteaban,

agotando siempre todas las posibilidades de los escasos medios

disponibles.

Además de esta importante faceta como

arquitecto al servicio de la Administración y como autor de notables

ejemplos de arquitectura residencial en conjuntos de viviendas sociales,

Valls desarrolló un trabajo prolijo en otros campos de la arquitectura,

donde también llevó a cabo actividad profesional.

Durante los años 1970-71 es nombrado

arquitecto del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, dirigiendo diversas

obras entre las que habría que citar la remodelación de la Facultad de

Ciencias Económicas, actualmente Facultad de Filología en el Paseo de

Blasco Ibáñez de Valencia, y la codirección del Instituto Politécnico

-actual Escuela de Arquitectura Técnica y origen de la Universidad

Politécnica de Valencia-, junto con los arquitectos Hernández y Prat.

En el terreno de la promoción privada no

deben dejar de mencionarse algunas obras significativas de las que es

autor o en las que participó activamente. Varias de estas obras fueron

realizadas para clientes muy representativos de la sociedad de la época

por su vinculación a los grandes encargos arquitectónicos de la Valencia

de los años 50 y 60 como la inmobiliaria VICOMAN, introductora en la

ciudad de las comunidades de propietarios; la empresa Valenciana de

Cementos, para la que remodela y amplia las oficinas de la manzana de la

calle Jorge Juan esquina calle Colón; o el propio Gerardo Bacharach, para

quien realiza, además de la dirección de obra del citado proyecto de

Gutiérrez Soto en el chaflán Cirilo Amorós- Isabel la Católica, el

edificio frente a la Basílica en la Plaza de la Virgen, ciertamente de

menor interés pero premiado por la Cámara Oficial de la Propiedad

Urbana.

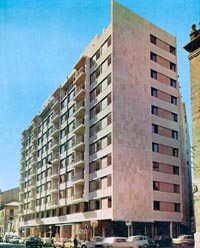

Otro ejemplo de la calidad arquitectónica

que alcanzaron algunas de estas realizaciones son los edificios en altura

para VICOMAN en la calle Cronista Carreres-El Justicia, que lleva a cabo

en colaboración con el arquitecto García Sanz, con quien se había

asociado en 1962 y con quien trabajará durante veinte años, hasta el

cierre del estudio en 1982 y la disolución de la sociedad común debido a

la atroz crisis económica que dio al traste con muchos de los estudios de

arquitectura valencianos a principios de los años ochenta.

En el ámbito de la arquitectura vinculada

al turismo de sol y playa, se encuentran muestras de excelente

arquitectura en la producción de Vicente Valls, siendo necesario hacer

alusión a la urbanización y los apartamentos de “las Playetas de

Bellver” en Oropesa del Mar, y a la urbanización y complejo “Tres

Carabelas 3” en la playa de Pinedo. Este último, también construido

para VICOMAN, es un complejo de 132 apartamentos en tres bloques de 7 a 13

plantas, sabiamente articulado para garantizar iluminación, ventilación

cruzada y vistas al mar, sin interferencias entre los edificios. El

cuidado puesto en la composición de la estructura de hormigón y los

cerramientos de ladrillo evidencian una claridad de imagen y una

preocupación por el rigor constructivo en un entorno que termina siendo

realmente beneficiado por la implantación de la obra.

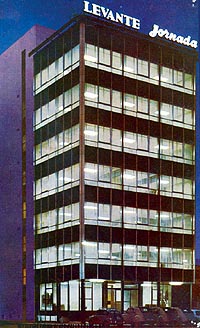

Los años 70 son para Vicente Valls una

época de prosperidad donde su ya consolidado estudio recibe numerosos

encargos. Especialmente importantes son aquellos que le proponen grandes

bancos para los que construye diversas oficinas y sucursales en Valencia y

sus alrededores como la Sede Regional del Banco Hispano Americano

(1970-72), en la calle de las Barcas o la del Banco Coca (1975-76) en la

calle Lauria, que codirige con Rafael de la Hoz Arderius. Ambas piezas en

una línea claramente mucho más formalista que las austeras realizaciones

de sus inicios.

La última obra realizada por Vicente Valls

fue la rehabilitación integral del edificio de la Plaza de Tetuán de

Valencia para albergar el Centro Cultural de Bancaja. Al finalizar este

proyecto concluyó su vida profesional reingresando, en 1984, en el cuerpo

de arquitectos al servicio de la Hacienda Pública, hasta su jubilación

forzosa en 1989.

El Premio a la Trayectoria Profesional del

COACV, a Vicente Valls, por Acuerdo de Junta de Gobierno de 29 de junio de

2005, como “Mestre Valencià d’Arquitectura”, supone para este autor

un nuevo reconocimiento que viene a sumarse a la Mención que ya en 1973,

el Colegio de Arquitectos de Valencia y Murcia le había otorgado por su

trabajo en el ámbito de la vivienda social.

José Parra Martínez |

At

the age of 81, Vicente Valls has received the Mestre Valencià d’Arquitectura

lifetime achievement award from the College of Architects of the Valencian

Community. Vicente Valls was born in Alcoy in 1924 and studied at the

Escuela Tecnica Superior de Arquitectura in Madrid, where he obtained his

architecture degree in 1951. In 1965 he graduated as PhD Architecture.

Although he made a brief incursion into the realm of academe when he

taught Construction II at the University of Valencia during the 1969-70

academic year, his life has mainly been bound up with the independent

practice of his profession. The great number and high quality of his

designs and built works stand as testimony of his ability throughout a

career that he himself can only describe as a life of dedication, high

demands and hard work in order to offer his clients the most rigorous

solutions.

Indeed, Vicente Valls is above all an architect

whose accomplishments spring from his sense of responsibility. While he

was an architecture student, his father, Vicente Valls Gadea, who was also

an architect, fell incurably ill. Because of the family’s delicate

situation, as the eldest of the nine children he found himself obliged to

complete two years’ courses each year and lose no time in taking charge

of his father’s studio, commissions and clients. Consequently, he

embarked on his professional career in 1951 by directing the works already

started by his father, particularly in blocks of flats.

That same year he won the post of Instituto de

Colonización architect in a competitive examination in which he came

first. For family reasons he had to relinquish the position but in 1953,

also by competitive examination, he became a Spanish Treasury architect.

His first posting was Albacete (1954-57), followed by Valencia. In 1961 he

requested extended leave of absence in order to fulfil his obligations as

architect of the Obra Sindical del Hogar (OSH), as in 1957, precisely the

year when the River Turia flooded Valencia, he had been appointed to a

civil service post in this organisation, for which he designed and built

urgent solutions: the large social housing estates for which he is best

known.

During this same period he replaced his father (who

was also a Valencia City Architect) at the Compañía de Tranvías tram

company and directed the work on various schools, as well as designing

various housing estates for workers’ cooperatives, such as those in

Tabernes Blanques and Chelva, and the Grupo San Rafael in Buñol,

commissioned by the Compañía Valenciana de Cementos.

At the same time he was also working on private

developments, directing work for Gerardo Bacharach on the block of flats

on the corner of Cirilo Amorós and Isabel la Católica streets (1956-57)

designed by Luis Gutiérrez Soto. Vicente Valls, who only met the famous

architect on the three occasions when he visited the site, was in charge

of the entire materialisation of this project and was responsible for the

meticulous, expressive brickwork that is a feature of the building’s

image.

His major architectural and town planning work for

the government from the 1950s to the 1970s, generally in collaboration

with other civil service architects, includes the Vicente Mortes complex

(1972-74) with García Sanz and Mensua, a 1200 housing unit development in

Avenida Hermanos Maristas, on the Fonteta de San Luis estate in Valencia;

the Virgen de los Desamparados housing complex (1954-62) in Avenida del

Cid, Valencia, in conjunction with Costa, Cabrero and Tatay; or the 1800

housing units of the Barrio de la Paz, on the Vistabella estate (1960-62)

in Murcia. These were featured in Hogar y Arquitectura magazine and are

currently at the centre of a dispute that has split the residents, city

hall and private developers into two opposing factions: one wants to

demolish them and speculate with the land and the other wants to preserve

and rehabilitate the complex, which has considerable architectural value,

excellent urban insertion and great environmental quality as a result of a

reflection, which is still surprisingly valid, on the city, public spaces,

green areas and social housing.

Within the sphere of mass housing developments by

public bodies, the importance of the Antonio Rueda complex (1969-72)

should, of course, be highlighted. This 1000-flat development in the

Avenida Tres Forques in Valencia, in collaboration with two other

architects, García Sanz and Marés, is a work of unhesitating mastery.

Built during the final stages of the well-known

social housing initiatives and the housing development policies of the

Franco régime’s successive governments from the post-war years to the

1970s, the Antonio Rueda development shows how important and necessary it

is to build a quality architecture that takes the restrictions imposed by

strict official regulations as a starting point: in this case they were

followed to the letter.

This major residential operation, which also had

links with the Obra Sindical del Hogar (an official housing organisation

that has since disappeared), involved building an estate of 1002

subsidised, price-controlled flats. The complex stands on a very large

site on the edge of the city of Valencia, a geographic and social setting

that was being populated at the time with numerous central government

developments to house the rural emigration to the city and, of course,

even at such a late date, to rehouse the victims of the Turia’s dramatic

floods. It is not difficult to trace the background to all these social

housing initiatives. The postulates of the Modern Movement had already

been fully accepted by a generation of architects that had also already

seen the large-scale Poblado Dirigido housing estates being built in

Madrid, Castile and Andalusia. These had been completed relatively

recently and were already occupied.

Indeed, certain parallels between the Antonio Rueda

complex and the Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto (1957-59) by Iñiguez

Onzoño and Vázquez de Castro may be observed in the organisation of the

blocks around public spaces and public infrastructure buildings. The

formal results of the Antonio Rueda development also appear to be indebted

to this estate in Madrid, as certain construction elements are employed to

create a final image with evident rationalist echoes.

However, the layout of the Valencian housing

development is based on different premises, as the topographical and

environmental conditions are totally dissimilar. In essence, it hinges on

modules, which Vicente Valls called ‘civic units’, of approximately

200 flats placed around public spaces. The successive repetition of these

modules defines the structure of the whole, solving its urban insertion

through addition and facilitating the global reading of this intervention.

At the same time, this strategy is sufficiently flexible to accept and

adapt to the geometrical irregularities of each unit and of the site as a

whole.

As in his project for the Vistabella estate in

Murcia, in the Antonio Rueda development Vicente Valls resorted to

strategic emptying to create the garden areas, for the use of residents

and the public, that enhance the environmental quality and urban nature of

the architecture. In the Avenida de Tres Forques development, however, the

provision the architects made for future collective facilities was indeed

to stand in good stead as a basis for the later construction of

educational infrastructure. In the event, this provision influenced the

volume of each unit, which finally took the form of two parallel

eight-storey blocks with a further perpendicular four-storey block that

contains the commercial premises and a connecting platform of

single-family duplexes, a decision which again harks back to Caño Roto.

Two twelve-storey tower blocks placed at either end add the finishing

touch to the complex.

Vicente Valls himself, referring to the Antonio

Rueda complex, said that because of the budget limitations 1 and the

strict rules that defined specific dimensions for each room, layouts,

geometries, independences and even the position of furniture, his team of

architects essentially had to concentrate on planning the open spaces and

the siting of the blocks, where the rules did allow greater freedom, and

tried to make the best use of these by designing meeting places that would

encourage neighbourly relations and that future occupants would enjoy.

Thus, fleeing any conceptual reference to modernist design, Valls simply

explained that in reality, his work was confined to creating genuine

social relationship spaces, as he was convinced that appropriate sunlight,

gardens and trees would make for a better place and a more human

environment where the residents would feel at home. This attitude again

shows an accomplished architect, like so many true professionals at the

time who, having accepted the postulates of modernism (unconsciously even,

perhaps), made architecture advance 2 because their work shunned any

gratuitous innovation and aimed to solve problems in an intelligent way,

exhausting all the possibilities afforded by the scarce resources at their

disposal.

As well as this important facet as a civil service

architect who designed notable examples of residential architecture in

social housing projects, Valls’ professional activities also included

prolific work in other fields of architecture.

During 1970-71 he was appointed a Ministry of

Education and Science architect. In this capacity he directed a number of

works, including remodelling the Economics Faculty (now the Philology

Faculty) on Paseo Blasco Ibañez in Valencia and co-directing the

Polytechnic Institute building (now the Technical Architecture School, it

was the origin of the Polytechnic University of Valencia) with the

architects Hernández and Prat.

In the field of private developments he also

designed or took an active part in various significant works. Several of

these were for clients whose connections with the major architectural

commissions in the Valencia of the 1950s and 1960s made them highly

representative of the society of that period, such as the VICOMAN property

company, which introduced Valencia to owners’ associations; Valenciana

de Cementos, for which he remodelled and extended the company’s office

in the block on the corner of Jorge Juan and Colón streets; or Gerardo

Bacharach, for whom he not only directed the work on Gutiérrez Soto's

project on the Cirilo Amorós - Isabel la Católica street corner,

mentioned above, but also built the building opposite the Basilica on the

Plaza de la Virgen, winning a prize from the Official Chamber of Urban

Property.

Another example of the architectural quality of some

of his work is his high-rise buildings for VICOMAN in Cronista Carreres -

El Justicia streets, in collaboration with García Sanz. He went into

partnership with this architect in 1962 and they worked together for

twenty years, until 1982, when the studio closed down and the partnership

was dissolved as a result of the savage crisis that wiped out many

Valencian architecture studios in the early eighties.

There are examples of excellent architecture by

Vicente Valls in the sphere of sun and sand holiday architecture,

particularly the urbanisation and apartments of the Playetas de Bellver in

Oropesa de Mar and the urbanisation and Tres Carabelas complex 3 at Pinedo

beach. The latter, which was also build for VICOMAN, is a 132 apartment

complex of three blocks that rise from 7 to 13 storeys, superbly sited to

ensure light, cross-ventilation and views of the sea from each, unhindered

by the others. The care taken over the composition of the concrete

structure and brick walls show a clarity of image and a concern for

rigorous construction in a setting that when all is said and done,

actually benefits from the insertion of this work.

For Vicente Valls, the 1970s were a prosperous

period. His studio was already well-established and received numerous

commissions. Particularly important were those from major banks, for which

he built a number of offices and branches in Valencia and the surrounding

area, such as the Banco Hispano Americano regional headquarters (1970-72)

on Calle de las Barcas or that of the Banco Coca (1975-76) on Calle

Lauria, which he co-directed with Rafael de la Hoz Arderius. Both are

clearly on far more formalist lines than the austere works of his early

period.

The last work by Vicente Valls was the integral

rehabilitation of the building on Plaza de Tetuán in Valencia to house

the Bancaja Cultural Centre. He ended his professional life on completing

this project and rejoined the Spanish Treasury corps of architects in

1984, until his forcible retirement in 1989.

The Mestre Valencià d’Arquitectura, the COACV

Professional Career Prize awarded to Vicente Valls by Resolution of the

Board of Directors dated 29 June 2005, is a further honour for this

architect, who in 1973 was awarded a Mention by the College of Architects

of Valencia and Murcia for his work in the field of social housing.

José Parra Martínez |

|