|

Mención

COACV 2005-2006/2005-2006

COACV Mention Trabajos documentales, publicaciones/Documentary works, publications |

||

|

Arquitectura de tierra en el sur de Marruecos. El oasis de Skoura Earth architecture in the south of Morocco. The Skoura oasis

|

Vicent Soriano Alfaro | |

| Extracto

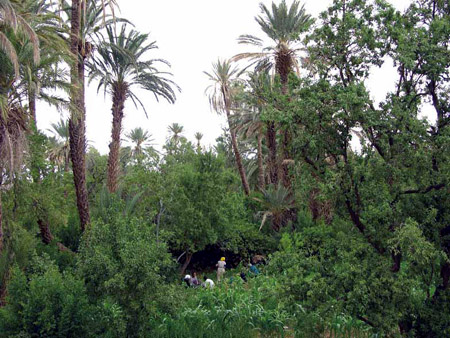

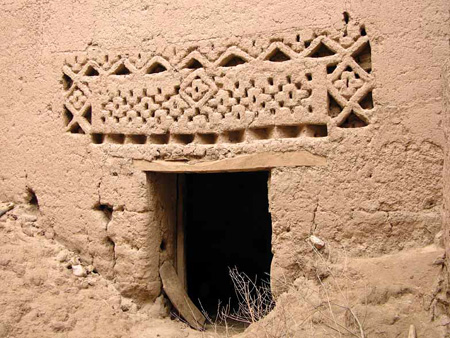

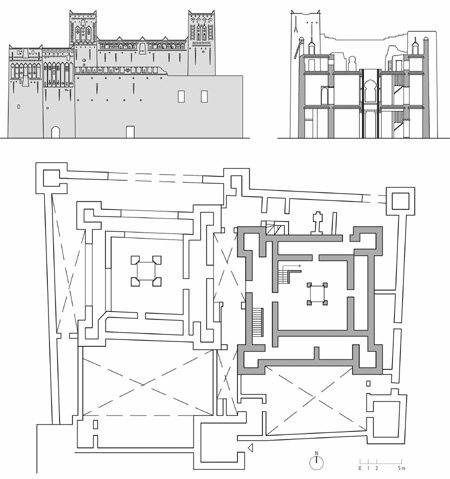

del capítulo: Descripción de las tipologías arquitectónicas Las palabras alcázar y alcazaba, que derivan de los nombres árabes qsar y qasba, denominan respectivamente a la fortaleza o palacio donde vivían los gobernadores musulmanes y al recinto fortificado que encerraba la vivienda del gobernador con el acuartelamiento de la guarnición. Ambos términos tienen ese significado tanto en los antiguos territorios de Al Andalus, como en la mayor parte del Magreb. Sin embargo, al sur del Gran Atlas el significado de ambas palabras es diferente, pues se emplea el término qsar, cuyo plural es qsur, para denominar a los poblados protegidos por una muralla con torres de vigilancia, mientras que el término qasba, cuyo plural es qasabat, define los conjuntos residenciales fortificados que generalmente pertenecen a personajes con poder, ya sea el amghar, jefe de fracción de una tribu; el caíd, jefe de tribu o gobernador de una región, o al makhzen que es la representación del sultán. Existe una tercera tipología residencial, que los habitantes de la zona denominan en beréber tighremt, cuyo plural es tighremat’n, y que corresponde a la vivienda familiar fortificada, que puede darse tanto en el interior de los poblados amurallados como aislada fuera de él, aunque en este último caso lo habitual es que se encuentren varias y con una cierta proximidad entre ellas. Este término beréber es el diminutivo de ighrem, plural ighremán, que se emplea tanto para denominar al qsar, como para señalar en algunas zonas a los graneros colectivos, de los que hablaremos más adelante. Hasta aquí los tres tipos de edificación residencial tradicional de la región, pero se dan además otros tipos cuyo uso no es específicamente el residencial sino que está ligado bien a la guarda y almacenaje de productos o bien al culto religioso, aunque en ocasiones y como veremos más adelante, ambos pueden presentarse juntos. Una de las construcciones más antiguas del sur la constituyen los graneros colectivos que, como hemos dicho anteriormente, se denominan ighremán, en singular ighrem, o también agadir según la zona. Existen de tipos y materiales muy variados y han servido para guardar las reservas alimenticias y también para proteger a las personas y al ganado del poblado de los ataques del exterior. El mausoleo o santuario contiene la tumba de un santón, morabito o marabú; es lugar de peregrinación y culto y es bastante común en todo Marruecos y, de forma especial, en la zona objeto de estudio. Su tipología es constante, con muy pocos elementos que varíen de un modelo a otro. Esta edificación recibe el nombre de qubba, palabra árabe que significa bóveda o cúpula, haciendo referencia a las pequeñas bóvedas que siempre cubren el espacio central de la edificación. Hay que señalar que en la literatura occidental se ha utilizado tradicionalmente la palabra morabito o marabú (cuyo significado es el de persona piadosa o santón musulmán) para designar la construcción donde reposan sus restos. Otra de las tipologías de carácter religioso son las zagüías que son establecimientos fundados por un santón o sus descendientes dedicados especialmente a la enseñanza, al sermón y a la reunión de adeptos, y en su conjunto arquitectónico conviven generalmente el mausoleo del fundador y la residencia de la familia marabútica. En ocasiones, particularmente en el caso de Skoura, como veremos más adelante, existe un mausoleo dentro del recinto de los graneros colectivos y a su santón se le encomienda la protección de los productos almacenados. A pesar de ser la mezquita la construcción que ocupa el lugar central en la arquitectura islámica, no se dedica un capítulo específico a su estudio por dos razones: la imposibilidad de acceso y su renovación continuada. A diferencia de otros países musulmanes, en Marruecos no se permite el acceso de los no creyentes al interior de las mezquitas, por lo que nos ha sido imposible su estudio. Hay que añadir, que el fervor popular hace que éste sea el edificio mejor conservado de la comunidad, lo que conlleva su reparación continua y en muchos casos la reconstrucción con nuevos materiales, al menos en nuestra zona de trabajo donde el material básico de la construcción ha sido tradicionalmente la tierra. A modo de ejemplo señalaremos que en todo Skoura sólo encontramos, en el caserío de Roda en Oulad Yaagoub, una parte de una mezquita que conservara su construcción original de tapia y su antiguo alminar de tierra. No obstante hablaremos algo más sobre este tema en el capítulo dedicado a los qsur de Skoura, donde entre sus restos se ha encontrado la correspondiente mezquita. Otro de los tipos tradicionales en la arquitectura musulmana que este estudio no trata específicamente, por no existir en esta zona, es el funduq. De esta palabra árabe deriva la española fonda, pero en otros países del Islam donde también esta tipología está muy extendida se emplea el término caravansaray o jan para denominarla. Son edificios que ofrecen alojamiento a viajeros y comerciantes, generalmente son de planta rectangular o cuadrada con un gran espacio central alrededor del cual se organizan las habitaciones, los almacenes y los establos. Existen excelentes y numerosos ejemplos en las grandes ciudades de Marruecos y en los demás países árabes, sin embargo, la mayoría de las veces en los qsur de los valles presaharianos el funduq se reduce a un pequeño local junto al acceso principal. El qsar Los qsur son poblados amurallados, flanqueados de torres en sus esquinas y, según su longitud, también en las partes intermedias de los lienzos de muralla con el fin de reforzar la vigilancia y defensa. Su administración corresponde a la asamblea de jefes de familia, que escoge a un representante sobre el que recae la autoridad y representación frente a instancias superiores. Si el poblado no es muy grande esta persona recibe el nombre de muqádem, pero en poblados de mayor extensión puede existir un muqádem para cada uno de los barrios y en ese caso la autoridad de la totalidad del poblado recae sobre un shij. Algunas veces estos poblados son de planta cuadrada o rectangular, pero en otras ocasiones son de forma irregular, para poder adaptarse a los desniveles del terreno o al límite fértil del oasis, o como consecuencia de su propio crecimiento. La estructura urbana también varía de unos a otros, muchos disponen de una trama en cuadrícula, con una calle principal que actúa de eje a partir de la cual parten calles secundarias en sentido perpendicular. El estudio de estos modelos llevó a establecer al especialista en cultura bereber Emile Laoust la similitud con el desarrollo de las ciudades romanas a partir del cardo maximus y los decumani. Por el contrario, otros modelos poseen una trama urbana intrincada similar a la de las ciudades árabes. En ambos casos las calles se presentan cubiertas en muchos tramos por las edificaciones a nivel de la primera planta, dejando sólo pequeñas zonas descubiertas que actúan como pozos de luz, por donde ventila e ilumina el viario urbano. Con esto se consigue una protección frente al sol, el calor exterior y las tormentas de arena. El ancho de estas calles es de unos dos metros y posee un canal central para la evacuación de las aguas pluviales, que al mismo tiempo sirve para alejarlas de los muros y evitar así el deterioro de éstos. Los qsur son de muy variada extensión, desde aquellos que sólo están habitados por unas pocas familias hasta otros que pueden tener hasta tres mil habitantes. A partir de determinado tamaño se estructuran por barrios, que se corresponden con diferentes grupos étnicos y que pueden estar compartimentados por muros y puertas aislando a unos de otros. Al parecer los qsur de trazado complejo son los de origen más antiguo, mientras que los de trazado regular fueron fundados por las tribus que se sedenterizaron durante el siglo XIX. Los de morfologías irregulares obedecen tanto a la seguridad que éstos ofrecen frente a los ataques, como al resultado de una construcción por fases, consistente en sucesivas ampliaciones y como consecuencia de las necesidades derivadas del aumento de la población. La mayoría de los qsur solo tienen un acceso, pero los hay con varias entradas que pueden conectar diferentes barrios con el exterior, o bien estar preparados para la conexión de diferentes enclaves del entorno con el qsar. Una de las formas de acceso más habituales es en zigzag, con la puerta perpendicular al lienzo de muralla y creando un espacio cubierto intermedio entre el exterior y el interior, donde normalmente hay un banco para sentarse, que se utiliza a veces en las reuniones de la asamblea de cabezas de familia y donde pernocta el guardián. En otras ocasiones el acceso puede ser una simple puerta sobre la muralla que puede estar flanqueada por altas torres. Próximo al acceso suele haber un gran espacio libre descubierto, a modo de plaza, donde se reúne la comunidad y celebra las fiestas y las bodas, que coinciden en la misma época todos los años y son comunitarias, durando varios días las festividades. Los equipamientos comunitarios del qsar varían en función de su importancia, siendo los más usuales la mezquita (yamá), el baño público (hammam), la escuela coránica (madrasa), la fonda (funduq), el cementerio (yebania), las eras, el establo, el pozo (bir) y las fuentes. Como hemos señalado anteriormente, la mezquita no falta nunca en ningún poblado, de hecho es el elemento, a nuestro criterio, que determina el límite entre lo que es un pequeño qsar y una tighremt colectiva. Incluso puede existir más de una mezquita en los qsur más grandes. Generalmente éstas se sitúan próximas al acceso, son de forma sencilla y muchas veces carecen de alminar, utilizando la terraza, a la que se accede por una escalera, para que el almuecín haga la llamada a la oración. En la planta baja está la sala de abluciones, provista de agua, y la sala de rezar con el mihrab sobre el paramento orientado hacia La Meca. La amplitud de la sala de rezar se consigue mediante uno o varios pórticos de pilares unidos por arcos, situados en el centro de la sala, con lo que se obtiene el ancho de dos o más crujías. El hammam suele estar situado junto a la mezquita como un anexo a la sala de abluciones, compartiendo con ésta la provisión de agua. Hemos llegado a ver casos en los que el pozo de agua que surte a estas dependencias es el mismo al que acude la población para aprovisionarse, de forma que el brocal se encuentra entre el interior y el exterior, siendo accesible desde la plaza pública y también desde la zona donde se realizan las abluciones. Generalmente el hammam es de reducidas dimensiones y consta de una habitación con el pozo y la olla para calentar el agua y de otra sala con pequeños habitáculos donde la gente se lava. Nada que ver con los baños de las ciudades que constan de las tres salas tradicionales _fría, templada y caliente_ que junto al vestíbulo de recepción, que también hace las funciones de vestuario, constituyen los espacios básicos de su organización. La escuela coránica suele estar junto a la mezquita, a veces incluso sobre la sala de abluciones, accediéndose a ella desde la terraza que es a su vez la cubierta de la sala de oración, pues normalmente se trata de una única habitación donde se juntan los niños para el aprendizaje de los textos del Corán. El funduq está constituido, en la mayoría de los casos, por una simple estancia próxima a la puerta del qsar, y su existencia no es habitual hallándose tan sólo en aquellos poblados grandes por los cuales es frecuente el paso de viajeros. En los qsur pequeños se suele utilizar el vestíbulo de acceso que, como hemos dicho, está provisto de algún banco sobre el que se puede pernoctar. Tanto las eras como el cementerio se localizan fuera del recinto amurallado y ambos están constituidos por una zona de terreno plana, que en el caso de la era está limpio, es de forma circular y se sitúa en la parte recayente al secano. El cementerio se identifica por las piedras plantadas que delimitan la situación y el largo de la tumba, que generalmente se aprecia por el túmulo. Con mucha frecuencia hay un mausoleo, donde se encuentra enterrado un santón, con su edificación característica de la que se hablará más adelante. La vivienda -daar en árabe, taddart en beréber- del interior del qsar difiere de unos valles a otros, existiendo básicamente dos tipos, según disponga o no de patio. También dentro del qsar puede haber alguna tighremt propiedad de las familias más ricas y que destaca en la imagen del conjunto. En cualquier modelo de vivienda la planta baja se reserva para los animales mientras que el resto de plantas se destina al almacenamiento de las reservas alimenticias, la cocina y los dormitorios. La cocina está compuesta por el horno para el pan y un par de fogones, todo ello de tierra como el resto de la vivienda. La terraza se utiliza para el secado de los productos agrícolas, fundamentalmente dátiles y, durante las estaciones que el clima lo permite, como espacio para hacer vida, en especial las mujeres. Es también en la terraza donde acostumbra a encontrarse el cuarto de invitados, pues allí se recibe a las visitas y se hospedan los forasteros amigos de la familia, que suben por la escalera desde el acceso sin inmiscuirse en el ambiente del resto de la casa. El mobiliario es muy austero y casi siempre consiste en esteras, tapices y cojines sobre los que se descansa, se habla, se come y se duerme. La tighremt Es bastante probable que las primeras tighremat’n se construyeran en la montaña y que posteriormente su uso se extendiera también por los valles meridionales a finales del siglo XVIII o principios del XIX, donde, según Djinn Jacques-Meunié, en primer lugar se instalaron dentro del recinto fortificado de los qsur, más tarde en el exterior pero cerca de ellos y por último lo hicieron de manera aislada e independientes de los poblados de donde procedían sus moradores. La cantidad de tighremat’n construidas fuera del recinto de los qsur está en relación directa con la riqueza del territorio, siendo raras en tierras pobres y mal regadas y numerosas, como es el caso de Skoura, en zonas prósperas y con abundancia de agua, donde crecen palmeras, olivos, higueras, granados y otros cultivos. El territorio por el que se extiende el uso de la tighremt es mucho más reducido que el de los qsur, siendo el área de mayor densidad la del valle del Dadès. Su zona de implantación llega por oriente hasta el Tohdra, siendo la tighremt de Aït Amou, en Taghzout, la más oriental. Por el sur se extiende, posiblemente con la llegada de la tribu de los Aït Sedrat, hasta el curso medio del Drâa, y es probable que las más meridionales sean las de Aït Atman y Taznakht. Hay que señalar que, a diferencia de la zona del Dadès donde éstas constituyen el hábitat tradicional, la mayor parte de las tighremat’n de esta zona fueron construidas a principios del siglo XX por los caídes locales y en las décadas siguientes por los representantes de El Glaoui que intentaba controlar la región. A poniente, fuera de los antiguos dominios de El Glaoui sólo se encuentran las pertenecientes a los otros grandes caídes bereberes del Gran Atlas: los Goundafi y los Mtougga, pero en número reducido y construidas en piedra. El tipo básico de tighremt es siempre de planta cuadrada, o más exactamente cuadrangular, con torres esquineras que sobresalen de las alineaciones de la fachada. Generalmente, en paralelo al cerramiento exterior hay un segundo muro concéntrico que también define una planta cuadrada y que junto al primero conforma la primera crujía perimetral. El centro del espacio interior puede tener patio o no, siendo lo más usual la existencia de un pequeño pozo de luz delimitado por cuatro gruesos pilares de adobe, por donde se ventilan más que se iluminan las diferentes plantas del edificio. A este pequeño patio, de dimensiones comprendidas entre uno y dos metros de lado, se le llama en árabe ain ad-daar, es decir, el ojo de la casa, y en bereber y con el mismo significado tit n-tgemmi. Algunas veces sólo existe una pequeña abertura de sesenta u ochenta centímetros de lado por donde sale el humo de la cocina que suele estar instalada en la primera planta. Hay ejemplos donde no hay ningún sistema de ventilación e iluminación y el centro de la planta lo constituye una estancia cerrada. Las tighremat’n más modernas y con influencias ciudadanas, pueden poseer un patio de mayores dimensiones delimitado por ocho pilares, esto quiere decir que además de los de las esquinas tienen otro pilar al centro de cada uno de los lados. Este tipo descrito corresponde a una estructura de muros concéntricos en anillo, que puede estar completo o faltar una crujía en algún lateral. También está el modelo de muros paralelos en una sola dirección, disponiendo en este caso dos muros interiores de tal manera que con ellos y las fachadas opuestas, todos en paralelo, se forman tres crujías. Este tipo estructural se desarrolla siempre sin patio de ventilación. La situación de la escalera varía de unos modelos a otros. En aquellos que no poseen patio central, la escalera siempre se encuentra en la primera crujía, para cualquiera de los sistemas estructurales descritos y suele ser de dos tramos paralelos, es decir lo que se denomina escalera de ida y vuelta. En los casos que responden al sistema estructural anular y que disponen de patio, pozo de luz o hueco de ventilación, ésta se sitúa de manera indistinta en la primera o en la segunda crujía y su forma también varía, pudiendo ser de ida y vuelta o de dos tramos perpendiculares, es decir a escuadra. En función del número de plantas de que disponga la tighremt, los usos pueden estar más o menos compartimentados o gozar de mayor o menor superficie, pero en general obedecen a un mismo criterio de distribución por alturas. La planta baja se destina a los animales y al almacenamiento de las reservas de grano y forraje. En el primer piso y en la segunda crujía, está instalada la cocina de manera que pueda ventilar los humos y vapores a través del pozo de ventilación central, sirviendo las estancias situadas en la primera crujía para el almacenamiento de productos alimenticios. En el segundo piso se distribuyen las estancias para dormir y para estar los hombres. En la planta de terraza y en alguno o todos los lados del cuadrado, siempre se construye alguna estancia en la primera crujía que se destina a recepción y dormitorio de invitados y de modo alternativo a dormitorios de la casa cuando el clima lo permite. Las torres que forman parte del sistema defensivo y de vigilancia de la tighremt sobrepasan en altura a estas últimas estancias. Las fachadas son planas y sin ningún hueco ni ornamentación en su parte baja, a excepción de la puerta de acceso que suele situarse en el centro de uno de los lienzos del muro exterior. Las torres, que como se ha dicho sobresalen respecto de las alineaciones de las fachadas, poseen una leve inclinación en forma de talud en sus paramentos verticales, que también sobrepasan en altura la coronación de los lienzos de fachada. Los huecos, formados por pequeñas ventanas y troneras, sólo se sitúan en las plantas superiores con el fin de imposibilitar a través de ellos el acceso al interior. Las tighremat’n más modernas, que como hemos señalado muestran una cierta influencia de la arquitectura ciudadana, utilizan ventanas de mayores dimensiones, en muchos casos enrejadas, al tiempo que pierden elementos típicos del sistema defensivo como son las troneras o los matacanes. Los motivos ornamentales, como se ha explicado en el capítulo dedicado a los materiales y sistemas constructivos, se basan en las diferentes disposiciones de los adobes, formando un amplio friso en la parte superior de los lienzos de fachada y de las torres, a la misma altura que comienza en los muros. Las troneras, los matacanes y, en general cualquier hueco o elemento defensivo de la fachada queda integrado en la composición general de la ornamentación. La coronación de los lienzos de fachada y de las torres suele estar almenada con pequeños merlones que sirven más como elementos decorativos y de fijación del cañizo de protección de los muros, que como parte del sistema defensivo. La primera ampliación que se produce a partir del tipo base descrito también es bastante uniforme en todos los casos y consiste en la construcción de un recinto adosado a la fachada donde se encuentra la entrada. Esta nueva edificación dispone de torres en esquina, la mayoría de las veces de menor altura que las del edificio principal, una entrada en zigzag a través de un vestíbulo y estancias que se construyen en la crujía formada por el nuevo muro de cerramiento y otro paralelo hacia el interior que bordean un espacio abierto, a modo de patio, sobre el que también recae el acceso del antiguo edificio. Este es un modelo de ampliación que se ha dado en la mayoría de las tighremat’n existentes, pero también hay otros, que aún sin alejarse mucho del modelo expuesto en forma y extensión, muestran influencias ciudadanas o si se prefiere de la arquitectura de Marrakech, como consecuencia del poder y la cultura urbana del propietario. En estos casos, el patio o espacio libre central de la ampliación está constituido por un ryad delimitado por columnas que forman un porche en todos o alguno de sus lados. Algunas pocas tighremat’n siguieron creciendo en ampliaciones debido al poder y riqueza que iba adquiriendo el propietario y llegaron a convertirse en una qasba, como veremos en el próximo apartado. Un aspecto diferente al de las ampliaciones son las agrupaciones de diferentes tighremat’n que constituyen un conjunto fortificado sin llegar a ser un qsar, ya que el conjunto no es de gran extensión, no tienen equipamientos comunitarios y pertenecen a una única familia. La agrupación se puede dar de diferentes formas pero una bastante común es la de dos tighremat’n adosadas compartiendo el muro y las torres centrales, es decir la fachada por la que se adosan, incluso disponiendo ambas de la ampliación delantera descrita anteriormente. También se ha encontrado el caso de dos tighremat’n completas, separadas por un estrecho patio, con sus ampliaciones correspondientes por uno de los lados y un cerramiento exterior compuesto de muralla y torres, que abarca todo el conjunto. La qasba A finales del siglo XVIII en el extremo occidental del Gran Atlas, la familia de los Mtougga que vivía en la qasba de Bouaboud, entró al servicio del sultán para gobernar una pequeña tribu formada por cinco fracciones. Hacia el este, en el valle alto del Nefis, es la familia Goundafi la que desde su residencia en la qasba de Tagontaft, y más tarde también en la de Talat N’Yaqoub, controla esta parte del territorio. Éstos fueron los dos grandes caídes que controlaban la parte occidental del Gran Atlas. |

Extract from chapter :

Description of architectural typologies There is a third type of residence that the inhabitants of the area call tighremt, plural tighremat’n, in Berber, which refers to a family fortified home. This may be found inside a walled village or isolated outside it, although in the latter case, several such homes would usually be located in a certain proximity. The Berber term is itself is a diminutive of ighrem, plural ighremán, and is used both to denominate the qsar and to indicate collective granaries in some areas, as will be discussed later in this article. These are the three types of traditional residential building in the area, but there are also other types that are not specifically for residential use but are used for the protection and storage of products, or for religious ceremonies, although sometimes, as we will see later, both uses can be combined. One of the oldest constructions of the south are the collective granaries, which, as mentioned above, are called ighremán, singular ighrem, and also agadir in some areas. These are of very varied types and materials and served to protect food stocks and also to protect the people and livestock of the village from external attack. The mausoleum or sanctuary contains the tomb of a holy man, a marabout or marabú; it is a place of pilgrimage and religious ceremony and is fairly common across the whole of Morocco, particularly in the area under study. Its typology is constant, with very few elements that change from one specimen to another. This building is given the name qubba, an Arab word meaning vault or dome, referring to the little vaults that always cover the central space of the building. In occidental literature, the word marabout or marabú (which means a pious person or Muslim holy man) is used to designate the construction where his remains rest. Another type of building of religious significance is the zagüía, an establishment founded by a holy man or his descendents and especially dedicated to teaching, sermons and meetings of followers, which is generally a complex that also has the mausoleum of the founder and the residence of the marabout family. Sometimes, particularly in the case of Skoura as we will see later, there is a mausoleum within the precincts of the collective granary and the protection of the stored food is entrusted to its holy man. Although the building that is at the centre of Islamic architecture is the mosque, a specific chapter on its study will not be written here for two reasons: the impossibility of entering it and its continual renewal. In contrast to other Muslim countries, non-believers are not allowed access to the inside of the mosques, so it was impossible for us to study them. It should be added that popular fervour makes this the best preserved building in the community. This implies its continual repair and in many cases reconstruction with new materials, at least in our area of study, where the basic construction material has traditionally been earth. To give an example, in the whole of Skoura we only found a part of one mosque that still had its original cob wall construction and earth minaret. This was in the hamlet of Roda at Oulad Yaagoub. However, we will discuss this subject a little more in the chapter on the qsur of Skoura, where the corresponding mosque has been found among their remains. Another of the traditional types of Muslim architecture that this study will not specifically describe is the funduq because there are no examples in this area. The Spanish word fonda comes from this Arabic word, but in other Islamic countries where this typology is very widespread the terms caravansaray or jan are used. These are buildings offering lodging to travellers and merchants. They generally have a rectangular or square plan with a large central space around which the bedrooms, store rooms and stables are distributed. There are many excellent examples of funduq in the large Moroccan cities and in other Arab countries. However, in the majority in the qsur of the pre-Saharan valleys the funduq is reduced to small premises close to the main entrance. The qsar The qsur are walled villages, flanked by towers at the corners and, depending on their length, may also have intermediate towers along the walls in order to reinforce the vigilance and defence. They are administered by an assembly of heads of family, who choose a representative to be responsible for maintaining authority and representing the group to others. If the village is not very large this person is called muqádem, but in larger villages there may be a muqádem for each of the districts, in which case the authority for the whole village falls to a shij. Sometimes these villages are square or rectangular in plan, but other times they are irregular in order to adapt to unevenness in the ground or at the fertile limit of an oasis, or as a consequence of their own growth. The urban structure also varies from one to another. Many have a grid layout, with a main street acting as an axis from which secondary streets lead off in a perpendicular direction. The study of these models led the Berber culture specialist Emile Laoust to establish a similarity with the layout of the Roman cities, based on the Cardo Maximus (main street usually running north-south) and Decumani (secondary streets at right angles). By contrast, other examples have an intricate urban layout, similar to that of Arab cities. In both cases, the streets are partially covered in many areas by the first floors of the buildings, leaving only small uncovered areas acting as light wells to provide urban ventilation and illumination. In this way, there is protection against the sun, external heat and sand storms. The width of the streets is some two metres and there is a central channel for rain water drainage, which draws the water away from the walls to avoid damage. The qsur are of very different sizes, from those that are only inhabited by a few families to those that may have up to three thousand inhabitants. After a certain size, they are structured into districts that correspond to different ethnic groups and may be separated by walls and gates. It seems that qsur with complex arrangements are the oldest, while those that are regular were founded by tribes who settled during the 19th century. Irregular morphologies arise both from the need to provide security against attacks and as a result of phased construction, consisting of successive extensions as a consequence of the needs of a rising population. The majority of the qsur only have one entrance, but there are some with various entrances connecting different districts with the outside, or different enclaves of the surroundings with the qsar. One of the more common entrance arrangements is the zigzag, with the gate perpendicular to the line of the wall, creating an intermediate covered space between the exterior and interior, where normally there is a bench to sit on, where a guard will stay at night and which is sometimes used for meetings of the assembly of family heads. In other places the entrance may be a simple gate in the wall, which may be flanked by high towers. Close to the entrance there is often a large free uncovered space like a square where the community meets and celebrates festivals and weddings. These both occur at the same time each year and are communal, with the festivities often lasting several days. The community facilities of the qsar vary depending on its importance. The most common are the mosque (yamá), public baths (hammam), Koranic school (madrasa), inn (funduq), cemetery (yebania), threshing floors, stable, well (bir) and fountains. As we indicated before, the mosque is never absent from any village. In fact, in our opinion, it is the element that determines the dividing line between a small qsar and a collective tighremt. There can even be more than one mosque in the larger qsur. Generally these are located close to the entrance, are simple in form and often lack a minaret, using the terrace, reached by a staircase, for the muezzin’s call to prayer. On the ground floor is the ablutions hall, with water, and the prayer hall with the mihrab on the wall facing Mecca. The width of the prayer hall is achieved by placing one or more arcades of pillars linked by arches in the centre of the hall to obtain a breadth of two or more naves. The hammam is often located next to the mosque as an annex to the ablutions hall, sharing its water supply. Cases have been seen in which the water well supplying these facilities is the same as that to which the population goes for their domestic supply, so the parapet is located between the interior and the exterior, accessible both from the public square and from the area where the ablutions take place. Generally, the hammam is small and consists of one room with the well and the pot in which the water is heated and the other room with small cabins where the people wash. This is nothing like the baths in the cities consisting of three traditional halls, cold, warm and hot, where the basic spaces also include a reception lobby, which also functions as a dressing room. The Koranic school is usually next to the mosque, sometimes above the ablution hall, reached from the terrace which is, in turn, the roof of the prayer hall. It is normally a single room where the children meet to learn the Koran. The funduq is composed in most cases of a simple room close to the gate of the qsar. It is not common, as it is only found in those larger villages where travellers often pass. In the smaller qsur the entrance porch is normally used, as it usually has a bench where someone can stay the night. Both the threshing floor and the cemetery are situated outside the walled area and both are on an flat piece of land. In the case of the threshing floor this is clean, in the form of a circle and situated in the part adjoining the unirrigated fields. The cemetery is identified by upright stones marking the location and length of the grave, which is generally identifiable by its mound. Frequently, there is a mausoleum where a holy man is buried, with a characteristic style of building that will be described below. The house (daar in Arabic, taddart in Berber) inside the qsar differs between one valley and another, but there are basically two types, depending on whether or not it has a courtyard. Within the qsar there may also be some tighremt owned by the richer families, which stands out in the overall view of the village. In all types of home the ground floor is reserved for the animals while the other floors are used for food storage, kitchen and bedrooms. The kitchen contains the oven for baking bread and a couple of hearths, all made of earth like the rest of the house. The terrace is used for drying farm produce, mainly dates, and during the seasons when the climate allows, as a living space, especially for women. The terrace is also the place where the guest room is usually found, as it is where visitors are usually received and friends of the family from elsewhere are lodged, as guests can climb the stairs from the entrance without going through the other parts of the house. The furniture is very austere and almost always consists of rush mats, carpets and pillows on which to rest, talk, eat and sleep. The tighremt It is quite probable that the first tighremat’n were constructed in the mountains and that later their use extended also to the southern valleys at the end of the 18th or the beginning of the 19th century. According to Djinn Jacques-Meunié, they were first installed within the fortified precincts of the qsur, later outside but close by and lastly they were built alone and independent of the villages from which their inhabitants came. The number of tighremat’n constructed outside the precincts of the qsur is directly related to the fertility of the territory, being quite rare on poor, dry land and numerous, as in the case of the Skoura, in prosperous areas with plenty of water, where palms, olives, figs, pomegranates and other crops are cultivated. The extent of the territory where the use of the tighremt is common is much less than that of the qsur, with the area of the highest density being in the area of the Dades valley. They are found to the east as far as the Tohdra, the most easterly being the tighremt of Aït Amou, in Taghzout. In the south they extend to the middle course of the Drâa, possibly accompanying the arrival of the Aït Sedrat tribe, and the most southerly are probably those of Aït Atman and Taznakht. It should be pointed out that that in contrast to the area of the Dades, where these are the traditional homes, most of the tighremat’n of this area were constructed at the beginning of the 20th century by the local caids and in the following decades by the representatives of the El Glaoui, who tried to control the region. To the west, outside the former domains of El Glaoui, they are only found belonging to the other great Berber caids of the Great Atlas, the Goundafi and the Mtougga, but in small numbers and constructed in stone. The basic type of tighremt is always on a square floor plan, or more exactly quadrangular, with towers at the corners standing out from the lines of the facades. Generally, parallel to the external enclosure is a second concentric wall that also defines a square plan and which together with the first makes up the first perimeter span. The centre of the interior space may or may not have a yard: the most common is a small light shaft, delimited by four thick adobe pillars, which serves more for ventilating than illuminating the various floors of the building. This small well, measuring between one and two meters on each side, is called ain ad-daar in Arabic, meaning eye of the house, and tit n-tgemmi in Berber, with the same meaning. Sometimes there is only a small opening of sixty or eighty centimetres per side through which the smoke of the normally first-floor kitchen escapes. There are also examples where there is no ventilation or illumination system and the centre of the plan is a closed room. The most modern tighrematín with urban influences may have a larger courtyard, delimited by eight pillars: this means that in addition to the four at the corners, there is another pillar in the centre of each of the sides. This type described is a structure of concentric walls in a ring, which can be complete or may lack a bay on one side. There is also the model of parallel walls in only one direction, in which case two interior walls are placed so that together with the opposing facades, all running parallel, they form three bays. This structural type is always built without a ventilation shaft. The location of the stairs varies between models. In those without a central patio, the stairs are always in the first bay in all the structural systems described and are usually in two parallel flights, in other words a return staircase. In the cases where the structural system is in a ring and there is a courtyard or light shaft or ventilation hole, the staircase is situated either in the first or second gallery and its form also varies, being either a return staircase or two perpendicular flights. Depending on the number of floors in the tighremt, the uses may be more or less compartmentalised or be assigned more or less floor area, but in general they follow the same distribution pattern by floors. The ground floor is for animals and the storage of grain and fodder reserves. The kitchen is installed on the first floor in the second bay so that the smoke and fumes may be ventilated through the central shaft, while the rooms in the first bay are used to store foodstuffs. The bedrooms and living rooms for the men are on the second floor. On the terrace floor, on some or all the sides of the square, some rooms are always constructed in the first bay as reception rooms and bedrooms for guests and alternative bedrooms for the household when the weather allows. The towers that form part of the defensive and lookout system of the tighremt are higher than these rooms. The facades are flat and have no holes or ornamentation on their lower part, with the exception of the entrance door, which is often in the centre of one of the exterior walls. The towers, which stand out from the lines of the facades, as has been mentioned, have a slight inclination in the form of a slope on their vertical walls, which also exceed the height of the crowns of the façade walls. Openings formed by small windows or embrasures are only located on the upper floors with the aim of making it impossible to access the interior through them. The most modern tighremat’n, which as we have indicated betray a certain degree of influence of town architecture, have larger windows, in many cases with grills, and lose the typical defensive elements such as embrasures or machicolations. The ornamental motifs, as explained in the chapter on materials and construction systems, are based on different arrangements of the adobe bricks, forming a wide frieze on the upper part of the walls of the façade and the towers, at the same height all around. The small windows, machicolations and generally any opening or defensive element in the façade are integrated into the general ornamentation scheme. The crowning of the façade walls and the towers is usually castellated with small merlons that serve more for decoration and for fixing the cane coping protecting the walls than as part of the defensive system. The first extension from the basic type described is also fairly uniform in most cases and consists of the construction of a precinct adjacent to the facade where the entrance is located. This new building has towers at the corners, usually lower than those of the main building, a zigzag entrance through a lobby and rooms constructed in the bay formed by the new enclosing wall and another parallel wall towards the interior bordering an open, yard-like space where the entrance of the old building is located. This is the extension model for most of the existing tighremat’n. There are others, however, which without departing much from the model described in form and size, betray the influence of the city, or of the architecture of Marrakech, as a consequence of the power and urban culture of the owner. In these cases, the courtyard or free central space of the extension consists of a ryad delimited by columns forming a porch on all or some of its sides. A few tighrematín continue growing in size due to the power and wealth acquired by the proprietor and become a qasba, as we will see in the next section. A different aspect to that of extensions is the grouping of different tighremat’n to form a fortified settlement without becoming a qsar, since the group is not as large, does not have communal facilities and belongs to a single family. The grouping can take different forms, but one that is fairly common consists of two terraced tighremat’n sharing the central wall and towers, that is to say, the façade which they share, and both of them may even have the extension at the front that was described earlier. Another case that has also been found is two complete tighremat’n separated by a narrow yard, each with its extensions on one of the sides and an exterior enclosure composed of wall and towers surrounding the whole arrangement. The qasba At the end of the 18th century, in the extreme west of the Great Atlas, the family of the Mtougga, who lived in the Bouaboud qasba, entered into the service of the Sultan to govern a small tribe made up of five fractions. Towards the east, in the high valley of the Nefis, the Goundafi family ruled this part of the territory from its residence in the qasba of Tagontaft, and later also from that of Talat N’Yaquoub. These were the two great caids who controlled the western part of the Great Atlas. The central area of the Great Atlas, from Tizi-n-Tichka to beyond the valley of Todrha, was controlled for many years by the Glaoua family, originally from Telouet. From 1886, when Madani El Glaoui took over its leadership, the family started to expand and increase its power over this territory, firstly through a policy of alliances and marriages and later by force and through support from the Sultan and then from the French during the Protectorate. So in addition to enlarging the Telouet qasba where they established their family home, Madani El Glaoui and later his brother Thami, who was bashá of Marrakech in 1907, also enlarged those of other family members or of their halifas, such as those of Tazert, Taliwin, Izoggweir and Assarag. In this way they achieved dominion over those of Taourirt, Tamdakht, Tifoultout and Tameslá and built new ones in Skoura, Tinhir and other places with the aim of extending their control over new territories. As a result, the highest concentration of this type of building is found in the central part of the Great Atlas and its valleys. The Alaouite dynasty which has been governing Morocco since the middle of the 17th century originally came from the region of Tafilalet, situated to the south of the eastern part of the Great Atlas. This lineage too constructed various royal residences during the 19th century, such as those of Abbar, Ouled Abd El Halim and El Feida, among others. Ouled Abd El Halim was built as the residence of Moulay Er-Rachid, governor of Tafilalet and brother of Moulay Hassan, while El Feida is the qasba of the present-day royal family. There are two different types of qasabat. Some, like that of Tafilalet, follow the typology of an urban palace with various concentric walled precincts and a structure of courtyards surrounded by increasingly private rooms. Others generally have their origins in a tighremt, extended with more rooms and richness of finishes and ornamentation as the head of the family acquired greater power and wealth. There are also some of new construction, built at a time of family splendour and conceived from the beginning as authentic fortified palaces, which preserve elements and hints of Berber architecture but are influenced by the sumptuousness of urban palace architecture. The collective granary As was mentioned before in the introduction to this chapter, there are several names to designate the collective granaries, the use of which often dates back to times before the population settled. The terminological question becomes more complex on realising that the area where they are found in the interior of Morocco spans two zones of different Berber dialect: tachelhit and tamaziht. These approximately correspond to the west and east of the region respectively. So, in the Anti-Atlas or in the valley of the Sous this construction is called agadir, as the word ighrem has the meaning of ‘wall’ and ‘enclosure’, while in tamaziht the granary is called ighrem, a term that is also used to denominate the qsar, and the term agadir is used to mean ‘wall’. The collective granary is a building constructed by a clan in order to keep their goods in safety. In it, each head of family has a different cell or compartment protected by a door and a lock. Often it has served as a refuge for people and livestock against attack by enemy tribes, and being the most important and largest building in the community, it has also been used for the assembly of heads of family and to dispense justice. It is watched over by a guard who checks what the individuals who enter it are doing and it is normally surrounded by high walls, sometimes with watchtowers, so it also serves as a lookout post over the neighbouring territory when it is in a geographically strategic place. Although the western technical literature has generalised the use of the term ‘collective granary’, this gives the somewhat mistaken impression that the harvest is held in common, whereas in reality, it is a group of different individual family compartments in one collectively guarded building. The advantage of grouping the private goods of a community is that it makes it possible to construct a building of some importance, thereby improving the effectiveness of its defence. It seems that the first granaries were caves, ingeniously distributed on the slopes of the rocky cliffs. Even today some specimens have been preserved, especially in the eastern Great Atlas. In the built granaries there are three different types of layout: linear, with cells distributed on various floors on both sides of a main passageway; round towers, where the cells are distributed in a ring on various floors; and quadrangular, with a central lobby or courtyard, where the cells are distributed around this space and other passageways leading off from it. The construction materials used, which vary depending on the place and which determine the type, are stone and earth. However, sometimes both appear combined in such a way that the parts that present the greatest problems are constructed of stone, such as the base of the walls or the walls themselves, especially when they are exposed to greater and faster erosion due to their orientation, and the rest is cob-built. According to Djinn Jacques-Meunié, it is possible that the use of stone is more primitive and has been superseded by cob throughout the pre-Saharan oases area, as mentioned in the previous chapter.

|

|

|

||

| La zona

central del Gran Atlas, desde el Tizi-n-Tichka hasta más allá del valle

del Todrha, estuvo controlada durante unos años por la familia de los

Glaoua, originaria de Telouet, que a partir de 1886, en que Madani El

Glaoui tomó la sucesión familiar, comenzó a expandirse y a aumentar su

poder sobre el mencionado territorio, primero mediante una política de

alianzas y casamientos y más tarde mediante la fuerza, el apoyo del sultán

y de los franceses durante el Protectorado. Así, Madani El Glaoui y

posteriormente su hermano Thami, quien fue bashá de Marrakech en 1907,

además de engrandecer la qasba de Telouet, donde tenían fijada su

residencia familiar, también lo hicieron en otras de parientes o de sus

jalifas como las de Tazert, Taliwin, Izoggweir o Assarag, logrando el

dominio sobre las de Taourirt, Tamdakht, Tifoultout, Tameslá y edificando

otras nuevas en Skoura, Tinhir y otros lugares con el fin de extender el

control sobre sus nuevos territorios. Como consecuencia, en esta parte

central del Gran Atlas y sus valles es donde existe una mayor concentración

de esta tipología de edificio.

Por otra parte la dinastía alauita, que desde mediados del siglo XVII hasta la actualidad gobierna Marruecos, es originaria de la región de Tafilalet situada al sur de la parte oriental del Gran Atlas. Este linaje construirá durante el siglo XIX diferentes residencias reales como las de Abbar, Ouled Abd El Halim, erigida para servir de residencia de Moulay Er-Rachid gobernador del Tafilalet y hermano de Moulay Hassan, la de El Feida, donde se encuentra la qasba de la familia real actual, y otras. Se podría hablar de dos tipos diferentes de qasabat, mientras que unas como las del Tafilalet siguen la tipología de palacio urbano, con diferentes recintos amurallados concéntricos y una estructura de patios rodeados de estancias que van adquiriendo una mayor privacidad, otras, generalmente, tienen su origen en una tighremt que con la adquisición de poder y riqueza por parte del jefe de familia van ampliándose con más dependencias y enriqueciéndose en acabados y ornamentación. También las hay de nueva planta que se edifican durante el momento de esplendor de la familia y que desde el principio se conciben como auténticos palacios fortificados, conservando elementos y matices de la arquitectura bereber, pero influenciados por la suntuosidad de la arquitectura palaciega urbana. |

The linear-type granaries are generally long and have straight lines and predominantly right angles. They are also large and frequently have a lookout post. The cells are distributed on various floors, on both sides of a narrow central passageway. They are always constructed in stone. In order to make access to the higher cells possible, they are furnished with staggered slabs projecting from the walls that function as a staircase and access platform to the cell. Sometimes, the floor plan may be slightly curved in order to adapt to the terrain. This type of granary is found in the western Anti-Atlas area. | |

|

|

||

| El granero

colectivo Como ya se ha comentado en la introducción al presente capítulo, existe una variada terminología para designar a los graneros colectivos, cuyo uso, en muchos casos, se remonta a tiempos anteriores a la sedentarización. La cuestión terminológica se torna más compleja al constatar que su área de extensión en el interior de Marruecos abarca dos zonas de diferentes variantes dialectales del bereber: el tachelhit y el tamaziht, que corresponden aproximadamente al poniente y al oriente de la región que nos ocupa. Así pues, en el Antiatlas o en el valle del Sous, a esta construcción se le denomina agadir, pues la palabra ighrem tiene para ellos el significado de muro y cercado; mientras que en tamaziht, es ighrem, vocablo que también utilizan para denominar al qsar, y, sin embargo, emplean el término agadir para expresar muro. El granero colectivo es un edificio construido por un clan con la finalidad de guardar con seguridad sus bienes. En él cada jefe de familia posee una celda o compartimiento distinto que dispone de una puerta con cerradura. Muchas veces ha servido de refugio para personas y ganado frente a los ataques de tribus enemigas y, al ser el edificio más importante y grande de la comunidad, también se ha utilizado para realizar las asambleas de jefes de familia y para impartir justicia. Está vigilado por un guardián que controla la actividad de los individuos que acceden a él y normalmente está rodeado de altos muros, a veces con atalayas, sirviendo también como puesto de vigía del territorio cuando está situado en un lugar geográficamente estratégico. Aún cuando la literatura técnica occidental ha generalizado la denominación de granero colectivo, esto supone una cierta imprecisión por cuanto que presupone una puesta en común de las cosechas, cuando de lo que se trata realmente es del agrupamiento de los diferentes compartimentos particulares, que son de uso familiar, en un solo edificio guardado colectivamente. La ventaja de agrupar los depósitos privados de una comunidad es la de tener la posibilidad de construir un edificio de una cierta importancia, que mejora la eficacia de su defensa. Al parecer, los primeros graneros utilizados fueron grutas, ingeniosamente dispuestas en los flancos de los acantilados rocosos, de los que aún hoy se conservan ejemplos, especialmente en el Gran Atlas oriental. Respecto a los construidos se puede observar tres tipos diferentes de organización: los lineales, con las celdas distribuidas en varias plantas a ambos lados de una calle central; las torres redondas, que tienen distribuidas las celdas en anillo y en varias plantas, y los cuadrangulares de vestíbulo o patio central, cuyas celdas se distribuyen alrededor de este espacio y de otros pasos que se organizan a partir de él. Los materiales de construcción utilizados, que varían según los lugares y que determinan su tipología, son la piedra y la tierra, aunque a veces ambas aparezcan combinadas de tal forma que se realizan en piedra las partes más problemáticas como son los zócalos de los muros o los mismos muros, sobre todo cuando por su orientación están expuestas a un mayor y más rápido deterioro, y el resto se hace de tapia. Según Djinn Jacques-Meunié es posible que el uso de la piedra sea más primitivo y haya retrocedido ante la tapia en toda la zona presahariana de los oasis, tal como ya comentamos en el capítulo anterior. |

The round tower type of granary, which in reality has a more or less circular but always irregular floor plan, is also constructed of stone and has the external appearance of fat towers, small and squat, without high lookout points. The compartments are arranged in the form of a ring and there is a wide central space that can be partially uncovered. This type is only found in the area of Siroua. Quadrangular granaries are constructed in stone or earth and their formal and distributive characteristics reveal different solutions. Those of stone are generally cubic, with a rustic appearance and of very poor construction. In the interior there is a small quadrangular courtyard or a covered central corridor. These buildings are found on the northern slopes of the eastern Great Atlas, a high altitude area with a harsh climate that was settled at a late date. The cob-built granaries can have a central lobby, completely covered or with a small opening in the form of a light shaft, or a central uncovered courtyard that often has a dwelling for the guardian in the centre. The compartments are distributed around the central space, with a gallery giving access to those on the second floor. In some specimens, in place of the central covered lobby, there is a short central corridor and the cells are arranged around the sides. The majority of these types of granary have corner towers that are used as lookout posts. The roofs are always flat, accessible and also made of earth. Granaries with a courtyard are found in places where the climate is dry and not very harsh, generally on the southern slopes of the central and eastern Anti-Atlas and the western Great Atlas. Those with a covered lobby are found in the mountains where the winters are harsh, such as on the northern slopes of the eastern Great Atlas and the Siroua. The mausoleum and the zagüía In many cases, the building is not as old as the tomb itself. In other cases, both the tomb and the building have ceased to exist, the memory of the place being kept alive by some tree, especially the tamarisk or acacia, which are especially sacred trees. Sometimes, with the passage of time, even this has disappeared, leaving nothing more behind than the remains of the trunk or residues of the offerings. |

|

|

|

||

| Los

graneros que obedecen al tipo lineal, son en general largos, rectilíneos

y en ellos predominan los ángulos rectos, también son grandes y suelen

tener un puesto de vigía. Como hemos dicho, las celdas se distribuyen en

varias alturas y a ambos lados de una estrecha calle central. Siempre están

construidos en piedra y para posibilitar el acceso a las celdas superiores

se disponen losas de manera escalonada que vuelan desde las fachadas, de

modo que hacen la función de escalera y de plataforma de acceso a la

celda. A veces la disposición en planta se curva ligeramente con el fin

de adaptarse al emplazamiento. Este tipo de granero es propio de la zona

del Antiatlas occidental.

Los del tipo de torre redonda, que realmente consiste en una planta más o menos circular pero siempre irregular, también están construidos en piedra y tienen el aspecto exterior de gruesas torres, pequeñas y rechonchas, que no disponen de puestos de vigía elevados. Los compartimientos se sitúan de forma anular y en algunos casos existe un espacio central más amplio que puede estar parcialmente descubierto. Este tipo se da únicamente en la zona del Siroua. Respecto a los graneros de planta cuadrangular los hay construidos en piedra o en tierra y sus características formales y distributivas muestran diferentes soluciones. Los realizados en piedra son en general de forma cúbica, aspecto rústico y de construcción muy mediocre. En el interior de los mismos se encuentra un pequeño patio cuadrangular o un corredor central cubierto. Estas edificaciones se localizan en la vertiente norte del Gran Atlas oriental, zona de tardía sedentarización, gran altitud y clima riguroso. Los graneros de tapia pueden ser de vestíbulo central, cubierto en su totalidad o con una pequeña abertura a modo de pozo de luz, o de patio central totalmente descubierto, que dispone en muchos casos de vivienda para el guardián en el centro. Los compartimientos se distribuyen alrededor del espacio central, existiendo en la segunda planta una galería que permite el acceso a los mismos. Algunos ejemplos en lugar del vestíbulo central cubierto poseen un corto corredor central a los lados del cual se disponen las celdas. La mayoría de estos tipos de granero disponen de torres angulares que se utilizan como puestos de vigía. Las cubiertas son siempre planas, accesibles y también de tierra. El granero con patio se localiza en los lugares de clima seco y poco riguroso, general |

The buildings are small, of low height and square plan, and the most striking element that identifies them is a small dome covering the central part, which has given them the popular name by which they are widely known, qubba, which means ‘dome’ or ‘vault’ in Arabic. Another term used to denominate these constructions, at least in Skoura, is ruda, which means cemetery in Arabic. However, in other Muslim countries they are known by the name of turba, which in classical Arabic defines the function of the building as a place of burial. The exterior perimeter of the

construction is delimited by four orthogonal cob-built walls and the

interior usually has four central adobe pillars that support the dome. The

dome may have different shapes, although, at least in the south of

Morocco, the most common are the sugarloaf (long elliptical) shape or

rounded with an octagonal base. At other times they are covered with a

tiled hipped roof. |

|

|

Publicado por la Q

fundación caja de arquitectos. Colección Arquíthemas núm. 18.

I.S.B.N. 84-934688-0-0 |