María Teresa Santamaría

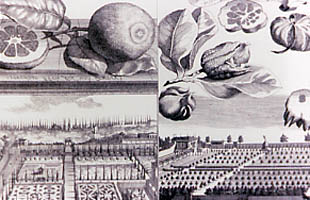

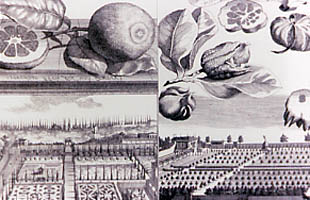

![En el siglo XVI, los oficios no incluían todavía al jardinero en las aucas dels oficis. Se hablaba del llaurador en sus distintas labores, entre ellas, el cultivo de cítricos.Eiximenis, en el siglo XIV ya citaba entre los frutos que se producían en Valencia: teronges, llimons, llimes, atzebrons y aranges. // 2. In the 16th century the occupation of gardener was not yet listed in the aucas de oficis. These mentioned the llaurador and his various tasks, amongst which was the cultivation of citrus plants. In the 14th century Eiximenis had already mentioned the fruits produced in Valencia: teronges, llimons, llimes, atzebrons y aranges [oranges, lemons, limes, aloes and pomelos]](008/008-02.jpg)

| Jardines

valencianos en la memoria María Teresa Santamaría |

![En el siglo XVI, los oficios no incluían todavía al jardinero en las aucas dels oficis. Se hablaba del llaurador en sus distintas labores, entre ellas, el cultivo de cítricos.Eiximenis, en el siglo XIV ya citaba entre los frutos que se producían en Valencia: teronges, llimons, llimes, atzebrons y aranges. // 2. In the 16th century the occupation of gardener was not yet listed in the aucas de oficis. These mentioned the llaurador and his various tasks, amongst which was the cultivation of citrus plants. In the 14th century Eiximenis had already mentioned the fruits produced in Valencia: teronges, llimons, llimes, atzebrons y aranges [oranges, lemons, limes, aloes and pomelos]](008/008-02.jpg) |

The memory of Valencian gardens |

|

|

|

La cartografía histórica de la ciudad nos muestra aquellos primeros jardines y huertos urbanos protegidos de las vistas mediante tapias, con un carácter mas o menos utilitario o suntuoso, pero entendidos siempre como una estancia más de la casa y por tanto, como un espacio reservado. La cultura del Islam marcó el carácter de la agricultura y jardinería, dejándonos una herencia que perduró largamente. Algunos jardines notables del siglo XV procedían de las casas árabes mas acomodadas, destinadas a conventos en la ciudad medieval que se configuró a partir de la Conquista, y sus jardines fueron transformados en huertos medicinales o de subsistencia para las órdenes religiosas, aunque sin perder por ello parte de su carácter ornamental. Observemos, que en la mayoría de los casos estos usos no eran excluyentes sino complementarios, pues tanto en el siglo XV como en el XVI, no encontramos aquí la palabra "jardinero" para nombrar un oficio reconocido. Solamente se contemplaba el cuidado del jardín si iba unido a una destreza especial de un labrador para tratar plantas de adorno por medio de técnicas que, como labradores de la huerta, conocían. Así, podemos comprobarlo en las aucas dels oficis, donde el ram de la agricultura incluye los oficios de: Llauradors, Llauradors jovens, Herbassers, Garbelladors, Cava - séquies y Llenyaters, pero no aparece ninguna palabra que haga referencia al jardinero. Sin embargo, a través de diferentes documentos, conocemos que el siglo XV fue una época brillante para la jardinería valenciana, pues tanto las plantas como los jardineros eran solicitados desde diferentes lugares y nombrados como Lligadors d’horts, es decir, labradores expertos en dirigir, injertar, entrelazar y ligar naranjos y mirtos especialmente. De los árabes, habíamos heredado entre otras plantas, el naranjo dulce, y entre otras técnicas, el injerto. Pero también nos habían hecho llegar un gusto por combinar aromas, formas y colores que convertía en verdaderos jardines los lugares que los lligadors trataban y por lo que sus conocimientos eran requeridos en muchos lugares. Para conocer cómo eran aquellos jardines y porqué era tan importante la colaboración de los lligadors, hemos de fijarnos en las notas y documentos escritos, incluso en las descripciones literarias y pinturas de la época. Algunos documentos de principios del siglo XV hablan ya de los huertos y jardines del Palacio Real, que había sido en su tiempo residencia del último rey moro. Así, en1406 el rey Martín el Humano escribió a Bartolomé Guerau pidiéndole que le enviara, para el jardín de su Palacio Mayor de Barcelona, algunos jazmines escogidos entre los más bellos que hubiese en el Real de Valencia, enviándolos enteros y con buen cepellón para que viviesen. Por otro lado, conocemos la contribución de plantas y jardineros valencianos en los jardines de Nápoles a través de Alfonso el Magnánimo, quien en 1450 mandó llamar a Guillermo Guerau y Pedro Franch para que plantasen, arreglasen y dispusiesen los huertos y jardines que el Rey quería hacer en Nápoles, dirigiéndose a ellos como: "Llauradors de l’horta de Valencia, mestres de plantar e lligar tarongers e murteres e fer jardins". Queda aquí bien claro que los jardineros eran "labradores de la huerta de Valencia, maestros en plantar y ligar naranjos y mirtos y en hacer jardines". Más adelante, también el Rey Fernando el Católico solicitó plantas y lligadors para sus jardines del Alcázar de Sevilla, pues así queda constancia en documentos de pagos fechados en Diciembre de 1484 y años sucesivos. Por los pagos periódicos efectuados a Miguel Bosch, deducimos que se trataba de la persona que tenía a su cargo los jardines del Alcázar de Sevilla, y su contribución era tan apreciada por Fernando el Católico, que a la muerte de Bosch se dirigió de nuevo a Valencia en busca de sucesor, y lo encontró en la persona de Francisco Aragonés. En cuanto a las plantas, hay notas de envíos de plantas a Sevilla desde Valencia en carabela, mirtos, jazmines, naranjos dulces y arangers entre otras. El esplendor e influencia de los jardines del Real aumentó durante el siglo XVI, pues Felipe II hizo mandar naranjos, limoneros y otros frutales del Real a Aranjuez en 1560, pero además, en años sucesivos se mandaron 6.000 plantas más, por lo que podemos reafirmar la procedencia valenciana de gran parte de las plantas de los jardines de Aranjuez, como ya lo había sido en los jardines napolitanos y en los del Alcázar de Sevilla, dejando constancia de que el Real servía entonces como ejemplo a otros jardines, como vivero de abastecimiento y como cantera de jardineros. Las descripciones de viajeros ofrecen mas datos sobre cómo eran estos jardines del Real. Jerónimo Munzer en 1494, da algunos detalles de lo que llama el jardín de la ciudad refiriéndose al Real, y dice de él que está "...muy bien plantado de limoneros, naranjos, cidros y palmeras. Con una cerca cubierta completamente con ramas y hojas de naranjos y adornado de mesas, altares, púlpitos naves, sillas y otros objetos hermosamente confeccionados de mirto... planta que era fácilmente guiada hacia todas partes para la formación de diversas figuras... jardines en general tan bien arreglados, que el visitante cree estar en el paraíso." Otra descripción es la del Señor de Montigny, quien se alojó en el Real en 1501 en una visita a Valencia: "El alojamiento es muy antiguo, pero el jardín es bellísimo, donde hay una cosa muy exquisita: es un naranjo del cual salen otros cuatrocientos, los cuales están tan bien llevados y conducidos que forman cubiertas y emparrados alrededor del jardín". Según estas descripciones, queda completamente claro el hecho de que a los jardineros valencianos se les llamase lligadors dada su especial habilidad para manejar el material botánico construyendo con él muros y objetos varios con los que se lograba una escenografía determinada en los jardines. Curiosamente, en el famoso libro veneciano publicado en 1499 El sueño de Polifilo, cuando se habla del jardín de la isla de Citerea, se describe una cerca de verdura compactamente hecha con naranjos, limoneros y cidros, y en otro lugar de la isla, una pérgola, cuyas ramas de limoneros naranjos y cidros se curvaban a modo de bóveda. El peregrino Polifilo muestra tal admiración ante semejantes construcciones de cítricos que recuerda de inmediato a los viajeros nombrados anteriormente hablando de los jardines valencianos y aunque en el caso del Polifilo se trata de un relato en clave simbólica, en algunos puntos se vislumbra, bajo el sueño, una trama real que nos indica una experiencia vivida por el escritor, en la que va aflorando toda una serie de influencias mutuas que en aquella época viajaban a través de la corte de los reyes. Además de los jardines del Real, también hay noticias de otros antiguos jardines valencianos, como el del infante D. Enrique de Aragón situado en la calle Sagunto, saqueado y reconstruido en 1521, fecha en la que encontramos documentos de pagos por la compra de "...cuatro docenas y media de hojas de espada para hacer remos a las galeras de mirto que hay en el jardín"; otras notas, por los pagos hechos al carpintero que ayudó a construir las naves de madera que cubrían de murta, y a un tal Montlleó que invirtió cuatro días en lligar el mirto de la nave. Este tipo de jardín y esta tradición jardinera continuó durante los siglos XVI y XVII. Las descripciones minuciosas de la Lonja en el siglo XVI hacen referencia al mismo tipo de vegetación, espacio dividido en cuatro cuadros, setos de mirto recortado, filas de naranjos, verdura sobrepuesta y la fuente, con muchos peces vivos. A su vez, Gauna describe, para las bodas de Felipe III en 1599, el mismo jardín de base y además "...ninfas figuradas de bulto de arrayán tañendo un instrumento, una en el centro de cada cuadro". Al oír esto, ya sabemos que nos hablan de los armazones de madera que se hacían para recubrir de mirto (también llamado antiguamente arrayán) pero por si hubiera alguna duda, hay un documento reconociendo la deuda con un tal Jerónimo Ayvar por haber confeccionado ninfas, barcas, pirámides, y haberlas recubierto de mirto. Deducimos pues, que para las ocasiones solemnes, se confeccionaban adornos efímeros que se recubrían como para las carrozas de las batallas de flores, y se adaptaban al trazado del jardín, constituyendo la verdura sobrepuesta. Las figuras de recorte vegetal, que actualmente nos sugieren el "ars topiaria" italiano, no dejaban de admirar en ese país, pues la literatura italiana, en una edición de 1651 de L’economía del cittadino in villa escrita por Vicenzo Tanara, se hace eco de la existencia de estos jardines valencianos, diciendo: "...en España, la más cálida región de Europa, en Valencia, ciudad no muy distante del mar, se ve un huerto con ingeniosísimos artificios plantados, en los que no sólo los setos de cidros engrosados y elevados hacen el papel de muros, sino que con estos mismos árboles se han formado estancias, logias, la iglesia, el altar, las sillas para los religiosos, fieles y laicos, cosa que debe parecer admirable a quien no sabe que de éstos frutos, en lugar cálido, se hace lo que se quiere y las ramas dobladas se reconducen..." La literatura es una fuente muy interesante para ir componiendo la trama de aquellos jardines, y en una época en que la información gráfica es muy escasa, también los grabados de los libros nos proporcionan con frecuencia claves importantes. Además, el aspecto mitológico estaba muy presente en aquellos jardines, y el mito de las Hespérides, nombradas ya por Hesiodo como "hijas de la noche que guardaban manzanas de oro al otro lado del océano", aparecen en el primer tratado de Botánica de la edad moderna Herbarum vivae eicones de Otto Brunfels (Strasburgo, 1530 –1536) cuya portada incluye una imagen de las tres ninfas que, ayudadas por el dragón, guardan de Hércules las manzanas de oro de propiedades milagrosas, identificadas como cidros, limones y naranjas. Sus aromas, colores, formas y sabores convertían al mítico Jardín de las Hespérides en un lugar encantado: Egle, custodiando el cidro, de formas curiosas y suaves aromas; Aretusa, custodia el limón, pieza preciosa para jardineros y médicos, y Espertusa custodia la naranja, de sabor y color intensos. Entre la ilusión mitológica y la investigación científica, las tres ninfas han ofrecido siempre a los especialistas tantas y tan diversas variedades que justificaban el entusiasmo del coleccionismo y han sido desde la antigüedad fuente constante de inspiración. Recordemos que el afán por disfrutar de una colección de cítricos, incluso en países en donde el clima no es propicio, dio lugar a las famosas orangeries de los principales jardines europeos, construcciones destinadas a conservar a cubierto las macetas de cítricos en las estaciones frías.La permanencia de la idea del jardín valenciano ha sido tan fuerte a través del tiempo, que de los inventarios de plantas encontrados en el Jardín Botánico de Valencia, en donde se revela su composición vegetal a principios de siglo XIX, llama la atención la gran cantidad de agrios empleados en las cercas de los cuadros, compuestas de naranjos y limoneros, setos de cidros y limas, junto a variedades diferentes de granados, mirtos, jazmineros, bojs y cipreses, además de 21 variedades de moreras híbridas y huerto para plantas aromáticas. Otro inventario muestra el cuadro de plantación de un huerto de cítricos con 32 variedades diferentes, hoy desaparecido Todo esto nos hace pensar que la Botánica y la técnica para encontrar nuevas hibridaciones y variedades, aún iban unidas a la presencia de ciertas especies vegetales y a una manera propia de hacer jardines con cercas y setos de toda clase de cítricos entre otros frutales y plantas exóticas. La técnica que permitía que los cítricos tuvieran diferentes usos y formas dentro del jardín, como cercas, setos, espalderas, se perdió aquí pero continúa en algunos jardines sevillanos y cordobeses, y también se conserva en Italia, en donde los cítricos siguen ocupando lugar preferente como planta ornamental de los jardines. En Valencia la tradición jardinera, recibida de manos de los árabes, se vio enriquecida muy pronto por la gran diversidad botánica de especies procedentes de las expediciones botánicas al nuevo mundo, que en una gran mayoría se aclimataron a esta tierra con éxito, pasando a formar parte de nuestros jardines como un alarde vegetal exótico asumido aún dentro de un esquema jardinero que se identificaba con el lugar. Pero a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, esta misma diversidad botánica, que debería haber sido una gran ventaja para nosotros, parece haberse vuelto en contra nuestra. La influencia de otros modelos jardineros de países con necesidades y condiciones climáticas diferentes a las nuestras, nos ha hecho perder el hilo de la propia historia jardinera, y hemos entrado en un tiempo en el que, en nuestras ciudades, se reclama más contacto con la naturaleza y paradójicamente, no se construyen jardines sino espacios verdes. En este momento en que la idea de jardín está desdibujada, cabría hacer una reflexión que nos permitiera distinguir lo que es un parque, un espacio libre, un jardín... El ciudadano parece tener una actitud confusa porque se le dirige a un modelo de consumo de espacios verdes, y en realidad se le está negando el jardín como modo de relación con la naturaleza que le permita disfrutarla con una mirada de contemplación, de reposo, de integración en un mundo de sensaciones que no implica consumo ni destrucción. El jardín, al contrario que un espacio verde, no se agota en su uso sino que tiene valor por sí mismo y su idea perdura en el tiempo. Por eso, quizás ahora que hacemos memoria, deberíamos retomar esa idea olvidada y seguir haciendo jardines. |

Historic maps of the city show the early urban gardens and orchards protected from view by high walls. Whether more or less sumptuous or utilitarian, they were always considered part of the house and consequently a private space. Islamic culture left its mark on the character of Valencia’s agriculture and gardening, bequeathing a legacy that survived for a long time. Some of the notable gardens of the 15th century belonged to the wealthier Moorish houses which became the convents of the medieval city after the Conquest. The gardens became the medicinal herb gardens and vegetable plots of the religious orders, although they did not lose their ornamental nature entirely. It should be noted that in most cases these uses were not exclusive but complemented each other mutually, as is shown by the fact that neither in the 15th nor in the 16th century is the word for gardener encountered here as the name of a recognised trade or occupation. The only concept of caring for the garden was that the labourers might have a particular skill in cultivating ornamental plants, using the horticultural techniques that were familiar to all the farmers and labourers of the irrigated area surrounding the city. This is confirmed by the aucas dels oficis [captioned pictures of occupations], where the ram de la agricultura includes Llauradors [farmers or farm workers], Llauradors jovens [young farmers], Herbassers [graziers], Garbelladors [sifters], Cava-sèquies [ditch diggers] and Llenyaters [woodcutters] but there is no word that refers specifically to gardeners. However, we know from various documents that the 15th century was a period of great splendour in Valencian gardening as both the plants and the gardeners were much in demand in different places. The latter were known as Lligadors d’horts [orchard binders] and were experts in shaping, grafting, intertwining and tying up trees and shrubs, particularly orange trees and myrtles. The Valencians had inherited the sweet orange, among other plants, and grafting, among other techniques, from the Moors. They had also inherited a taste for combining aromas, forms and colours that turned the plots where the lligadors worked into genuine gardens, hence the demand for their skills in many other places. To find out what those gardens were like and why the work of the lligadors was so important, we must turn to the written notes and documents and even to the literary descriptions and paintings of the period. Certain documents from the early 15th century already mention the orchards and gardens of the Palacio Real, the royal palace that had been the residence of the last Moorish king. In 1406 King Martin the Humane wrote to Bartolomé Guerau asking him to choose some jasmines for his Palacio Mayor in Barcelona. He was to select them from the most beautiful ones in the Real in Valencia and send them entire and with a good root ball so that they would live. We also know the contribution that Valencian plants and gardeners made to the gardens of Naples thanks to King Alfonso the Magnanimous, who in 1450 sent for Guillermo Guerau and Pedro Franch to lay out, plant and keep the gardens and orchards that the king wished to make in Naples. He addressed them as "Llauradors de l’horta de Valencia, mestres de plantar e lligar tarongers e murteres e fer jardins". It is quite clear here that the gardeners were "farmers of the Valencian plain, masters in planting and tying oranges and myrtles and in making gardens". At a later date, King Ferdinand the Catholic sent for plants and lligadors for his gardens in the Alcázar of Seville, as witnessed by documents showing payments made in December 1484 and subsequent years. From the regular payments made to Miguel Bosch it may be deduced that he was the person in charge of the gardens of the Alcázar of Seville. King Ferdinand appreciated his work so highly that when Bosch died the king again sent to Valencia to find a successor and Francisco Aragonés was chosen. As regards the plants, there are notes of plants being sent from Valencia to Seville by caravel: myrtles, jasmines, sweet oranges and pomelos were among them. The splendour and influence of the gardens of the Real increased during the 16th century, since Phillip II had orange, lemon and other fruit trees sent from the Valencian palace to Aranjuez in 1560 and in subsequent years a further 6000 plants were sent. We can therefore reaffirm that a large part of the plants in the gardens of Aranjuez were of Valencian origin, as they had been in the Neapolitan gardens and in those of the Alcázar of Seville, and note that at that time the Real was a model for other gardens, as well as a nursery that supplied plants and a school and source of gardeners. Travellers’ descriptions provide further information on what the gardens of the Real were like. Jerónimo Munzer, in 1494, gave some details about what he calls the gardens of the city, meaning the Real. He said that they were "...very well planted with lemon, orange, citron and palm trees. The surrounding wall is completely covered with orange branches and leaves and is adorned with tables, altars, pulpits, ships, chairs and other objects beautifully fashioned from myrtles... a plant that is easily trained in every direction to form diverse figures... the gardens are in general so well kept that the visitor believes himself to be in paradise". Another description is by the Seigneur de Montigny, who was lodged in the Real during a visit to Valencia in 1501: "The lodging is most antique but the garden is very beautiful, in which there is a most exquisite thing: it is an orange tree from which another four hundred spring, which are so well kept and trained that they form an arbour all around the garden". These descriptions explain why the Valencian gardeners were known as lligadors, given their special skill in training the plants and shaping them into walls and an assortment of objects to achieve a particular garden scenery. Curiously, the famous Venetian book Hynerotomachi Poliphili: the Strife of Love in a Dream, published in 1499, speaking of the island of Cythera, describes a wall of greenery entirely composed of orange, lemon and citron trees and, in another place on the island, a pergola where branches of lemon, orange and citron trees curve over to form a vault. The pilgrim Polyphilus shows such admiration for these citrus constructions that it immediately reminds one of the travellers descriptions of the Valencian gardens quoted above. Although the Strife of Love in a Dream is an allegorical narrative, there are moments when a basis in reality, glimpsed beneath the dream, gives an indication of the real-life experience of the writer and brings to the surface a series of mutual influences among the royal courts of the time. As well as the gardens of the Real, there are also reports of other ancient Valencian gardens such as that of Prince Henry of Aragon in Calle Sagunto. It was sacked and rebuilt in 1521 and there are documents showing payments for the purchase of "... four and a half dozen sword blades to make oars for the myrtle galleys in the garden" and other notes of payments to the carpenter who helped to build the wooden ships that were to be covered with myrtle and to someone called Montlleó who spent four days tying the myrtle to the ships.

This type of garden and this gardening tradition continued during the 16th and 17th centuries. The meticulous descriptions of the Lonja [Exchange] in the 16th century mention the same type of vegetation: the space divided into four beds with trimmed myrtle hedges, rows of orange trees, superimposed greenery and a fountain with many live fishes. Gauna, commenting on the wedding of Phillip II, describes the same basic garden and also "...myrtle shapes depicting nymphs playing an instrument, one in the middle of each square". On hearing this we already know that he is speaking of the wooden frames that were built to be covered in myrtle, but were there any doubt there is a document that recognises the debt to a certain Jerónimo Ayvar for having made nymphs, ships and pyramids and covered them with myrtle. It may be deduced that ephemeral decorations, covered in the same way as the floats for the ‘flower battles’, were constructed for special occasions and fitted into the layout of the garden to constitute the 'superimposed greenery'. Clipped plant figures, which nowadays call to mind the topiary art of the Italians, were a subject of admiration to the Italians of the time, as we know from literary references such as a 1651 edition of Vicenzo Tanara’s L’economia del cittadino in villa, which mentions the existence of these Valencian gardens. Tanara says that "... in Spain, the warmest region of Europe, in Valencia, a city not far from the sea, one may see an orchard with most ingenious planted artifices, where not only do high, thickened citron hedges act as walls, but with these same trees rooms, loggias, the church, the altar, the seats for the clergy, the faithful and the lay people have been formed, which thing must seem most admirable to those who do not know that of these fruits, in a warm place, one may do what one wills, and the branches are bent and extended..." Literature is a very interesting source for piecing together the layout of those gardens and, in a period for which pictorial information is very scarce, the engravings in the books often provide important clues. Moreover, the mythological element was very much present in those gardens and the myth of the Hesperides, described by Hesiod as "the daughters of the night who guarded golden apples on the other side of the ocean" appears in the first botanical treatise of the modern age, Herbarum vivae eicones by Otto Brunfels (Strasbourg, 1530–1560). The cover shows the three nymphs, aided by a dragon, guarding from Hercules the golden apples with miraculous properties, depicted as citrons, lemons and oranges. Their aromas, colours, forms and flavours make the mythical Garden of the Hesperides an enchanted place. Aegle guards the citron with its curious shapes and delicate aroma, Erytheis the lemon that is so precious to gardeners and doctors and Hespera the orange with its intense flavour and colour. The three Hesperides, between mythological illusion and scientific research, have always offered the specialists a number and diversity of varieties such as to justify the enthusiasm of collectors and be a constant source of inspiration since ancient times. Let us not forget that the yearning to enjoy a collection of citrus trees even in countries with an adverse climate led to the construction of the famous orangeries of the leading European gardens: they were built to keep the pots of citrus plants under cover during the cold season. The idea of the Valencian garden persisted so strongly down the ages that a striking feature of the inventories of plants in Valencia’s Botanical Garden, which reveal the composition of its plant collection at the beginning of the 19th century, is the large numbers of citrus species in the hedges around the beds. They comprised orange and lemon trees and citron and lime hedges together with different varieties of pomegranates, myrtles, jasmines, box and cypresses, 21 varieties of hybrid mulberry trees and a herb garden. Another inventory shows the planting pattern of a citrus orchard with 32 different varieties, which has since disappeared. From this one may deduce that botany and the techniques for discovering new hybrids and varieties still went hand in hand with the presence of certain plant species and a particular way of planting gardens, with walls and hedges composed of all types of citrus species among other fruit trees and exotic plants. The technique that enabled citrus species to be put to all kinds of uses and shaped into different forms in the garden, such as walls, hedges and espaliers, has been lost here but continues in certain gardens in Seville and Cordoba and is also preserved in Italy, where citrus species continue to be favoured as ornamental garden plants. In Valencia, the gardening tradition inherited from the Moors was soon enriched by a great diversity of botanical species brought back by the botanical expeditions to the New World. The great majority successfully acclimatised to this area and became part of our gardens as a display of exotic plants although still within a recognisably local garden type. However, from the second half of the 19th century onwards this same botanical diversity, which should have been a great boon to Valencia, seems to have turned against us. The influence of other garden models from countries with different needs and climates to our own has led us to lose the thread of our own gardening history. Nowadays our cities are demanding more contact with nature but, paradoxically, we are building green spaces rather than gardens. At present the idea of a garden has become blurred. We should reflect on and distinguish what constitutes a park, an open area, a garden... The public appears to be confused as a result of having been channelled into a green space consumption model and, therefore, denied the garden as a way to relate with nature, a way in which nature can be enjoyed with a contemplative eye, restfully, integrated in a world of the senses that does not involve consumption or destruction. Unlike a green space, a garden is not only for using, it has value in itself and the idea of it lasts over time. Now that we are remembering, perhaps we should take up this forgotten idea again and continue to make gardens. Translator’s note: Ferdinand of Aragon, married to Isabel of Castille: the Ferdinand and Isabel who became rulers of all Spain and (Isabel) commissioned Columbus’ expeditions to America. Translator’s note: also called shaddock, pumello or pompelmoose.

|

|

BIBLIOGRAFIA. A.A V.V.. " Il Giardino delle Esperidi".Gli agrumi nella storia, nella letteratura e nell’arte. A cura de S. Tagliolini y M. Azzi. Ed. Edifir, Firenze, 1996. A.A V.V. "Cartografía Histórica de la Ciudad de Valencia 1704–1910" Ayuntamiento de Valencia 1984. ABU ZACARIA, "Libro de la agricultura"(siglo XII) Imp. Real de Madrid, 1802. ALMELA Y VIVES, F. " Jardines valencianos". La semana gráfica. Valencia, 1945. ALMELA Y VIVES, F. "Valencia". Enciclopedia gráfica. Ed. Cervantes. Valencia, 1930. ASSUNTO, R. "Ontología y teleología del jardín "Ed. Tecnos. Madrid, 1991. BRUNFELS, O. "Herbarum vivae eicones". Strasburgo, 1530–1536. CAVANILLES A.J. "Observaciones sobre la Historia Natural, Geografía, Agricultura, población y frutos del Reyno de Valencia". Madrid, 1975, Ed. Facsímil Albatros, Bibliotheca valentina. Valencia, 1985. CARRASCOSA CRIADO, J. "Jardinería Valenciana". Elementos para el estudio histórico. Valencia, 1932. CLARICI., P.B. "Istoria e coltura delle piante..." Venezia, 1726. COLONNA, F. "Sueño de Polifilo".Trad. P.Pedraza .Murcia, 1981. DIEZ DE VELASCO, F. "Lenguajes de la Religión". Mitos, símbolos e imágenes de la Grecia antigua. Ed. Trotta, Madrid, 1998. INSAUSTI, P. "Los Jardines del Real de Valencia. Origen y plenitud. Ayuntamiento de Valencia, 1993. DIOSCORIDES, P. "Acerca de la materia medicinal de los remedios mortíferos". Trad. A. de Laguna. Edición facsímil de la de Amberes, 1555. Madrid, 1991. GARCIA MERCADAL, J. "Viajes de extranjeros por España y Portugal". Magrid, 1945. FERRARI, G.B. "Hesperides, sive de malorum Aureorum cultura et usu". Roma, 1646. GRIMAL,P. "Diccionario de Mitología Griega y Romana" Ed. Paidós. Barcelona, 1994. HESIODO. "Obras y Fragmentos: Teogonía. Trabajos y días". Ed. Gredos. Madrid, 1978. KRETZULESCO - QUARANTA ". Los Jardines del Sueño". Polifilo y la mística del Renacimiento. Ed. Siruela. Madrid, 1996. SALVADOR P. J., SANTAMARIA, M.T. "Valencia y los agrios: Del jardín de los cinco sentidos al huerto productivo burgués." Atti del V Colloquio Internazionale. Pietrasanta, 1995. SANTAMARIA, M.T."El Jardín de Monforte". Aproximación a la jardinería valenciana de los s. XVI al XIX. Valencia, 1993. TANARA, V. "L’economía del cittadino in villa". Ed. Dozza. Bologna, 1651. VOLKAMER, J.C. "Nürnbergischen Hesperidum", Nürnerg, 1708. BIBLIOGRAPHY Compilation "Il Giardino delle Esperidi".Gli agrumi nella storia, nella letteratura e nell’arte. A cura de S. Tagliolini y M. Azzi. Ed. Edifir, Firenze, 1996. Compilation "Cartografía Histórica de la Ciudad de Valencia 1704–1910" Ayuntamiento de Valencia. 1984. ABU ZACARIA, "Libro de la agricultura" (12th century) Imp. Real de Madrid, 1802. ALMELA Y VIVES, F. "Jardines valencianos". La semana gráfica. Valencia, 1945. ALMELA Y VIVES, F. "Valencia". Enciclopedia gráfica. Ed. Cervantes. Valencia, 1930. ASSUNTO, R. "Ontología y teleología del jardín" Ed. Tecnos. Madrid, 1991. BRUNFELS, O. "Herbarum vivae eicones". Strasbourg, 1530 - 1536. CAVANILLES A.J. "Observaciones sobre la Historia Natural, Geografía, Agricultura, población y frutos del Reyno de Valencia". Madrid, 1795 Facsimile edition, Albatros, Bibliotheca valentina. Valencia, 1985. CARRASCOSA CRIADO, J. "Jardinería Valenciana". Elementos para el estudio histórico. Valencia, 1932. CLARICI, P.B. "Istoria e coltura delle piante..." Venezia, 1726. COLONNA, F. "Sueño de Polifilo". Transl. P.Pedraza. Murcia, 1981 [Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: the Strife of Love in a Dream’]. DIEZ DE VELASCO, F. "Lenguajes de la Religión". Mitos, símbolos e imágenes de la Grecia antigua. Ed. Trotta, Madrid, 1998. INSAUSTI, P. "Los Jardines del Real de Valencia. Origen y plenitud. Ayuntamiento de Valencia, 1993. DIOSCORIDES, P. "Acerca de la materia medicinal de los remedios mortíferos". Transl. A. de Laguna. Facsimile of the 1555 Antwerp edition. Madrid, 1991. [de materia medica, book 6: poisons]. GARCIA MERCADAL, J. "Viajes de extranjeros por España y Portugal". Madrid, 1945. FERRARI, G.B. "Hesperides, sive de malorum Aureorum cultura et usu". Roma, 1646, GRIMAL, P. "Diccionario de Mitología Griega y Romana" Ed. Paidós. Barcelona, 1994, HESIODO "Obras y Fragmentos: Teogonía. Trabajos y días". Ed. Gredos. Madrid, 1978 [HESIOD, Works and Fragments: Theogony. Works and days]. KRETZULESCO - QUARANTA . "Los Jardines del Sueño". Polifilo y la mística del Renacimiento. Ed. Siruela. Madrid, 1996. SALVADOR P.J., SANTAMARIA, M.T. "Valencia y los agrios: Del jardín de los cinco sentidos al huerto productivo burgués". Atti del V Colloquio Internazionale. Pietrasanta, 1995. SANTAMARIA, M.T. "El Jardín de Monforte". Aproximación a la jardinería valenciana de los s. XVI al XIX. Valencia, 1993. TANARA, V. "L’economía del cittadino in villa". Ed. Dozza. Bologna, 1651. VOLKAMER, J.C. "Nürnbergischen Hesperidum", Nürnberg, 1708. |

|

|

|

|