|

Un acercamiento crítico a la obra de Le Corbusier exige construir

lecturas diagonales para corregir las inevitables deformaciones que, sobre

su personalidad y discurso arquitectónico, han producido las

excesivamente especializadas investigaciones disciplinares. Aproximarse

con rigor a su intensa trayectoria intelectual, a menudo repleta de

inseguridades y paradojas, supone contemplar su agitada vida como una

incesante actividad creadora dedicada a desvelar la realidad que se oculta

cifrada bajo las formas. Como ha apuntado Gregotti1, ningún

gesto en su trabajo parece estar decidido por razones puramente

estéticas. Inventar, significaba para Le Corbusier resolver un problema,

convertir la forma en un crisol de cuestiones, en una amalgama de

experiencias heterogéneas; en la conclusión necesaria de una búsqueda

continua y de una reflexión densa a partir de materiales complejos sobre

los que fundar las ideas estructurantes del proyecto.

Precisamente, uno de estos materiales más interesantes lo constituyen

las metáforas. El recurso metafórico en Le Corbusier no es una excusa

superficial; procede de la naturaleza profunda de la observación de las

cosas. Mediante la metáfora se anudan imágenes que participan tanto de

lo racional como de lo irracional, que emergen de un espíritu

hipersensible, permeable y poético, forjado entre varias culturas. Por

ello, las metáforas más tardías de Le Corbusier son, sin duda, las más

fecundas, pero también las más difíciles puesto que, con el paso del

tiempo, se tornan cada vez más opacas y herméticas a medida que el

arquitecto asimila las múltiples influencias que le brindan los distintos

territorios que visita. A través de las metáforas sus obras conjugan

desde eslóganes maquinistas con hechizantes figuras literarias, hasta

insólitos ecos surrealistas con las voces más antiguas de las

civilizaciones del Mediterráneo e, incluso, el dualismo del pensamiento

alquímico con los mitos cósmicos inmemoriales de las religiones de la

India2.

Sin considerar la justa importancia de este recurso sus formas

arquitectónicas no pueden explicarse del todo, y hasta pueden parecer

faltas de sentido si omitimos el inagotable potencial que encierra la

expresiva ambigüedad de este tropo. Resulta, pues, imprescindible acudir

a sus textos y, sobre todo, a su pintura –donde él mismo nunca se

cansó de repetir que residía el secreto de su arquitectura– para

encontrar, en el constante flujo de alegorías y metáforas que nutren el

imaginario de Le Corbusier, valiosas claves que permiten acceder, de un

modo más completo, a las inagotables enseñanzas de sus realizaciones

más brillantes y enigmáticas.

En este contexto, podemos proponer, en la obra de Le Corbusier, un

estudio del agua como la materia inspiradora de muchas de sus principales

metáforas. Hablaríamos entonces de un soporte de imágenes o, como lo ha

definido Gaston Bachelard3, de una metapoética del agua. No se

trata de reconocer un grupo particular de imágenes vagas y posiblemente

inconexas, sino de distinguir, en la unidad del elemento acuático, el

principio que las funda. Para precisar esta tarea, habrá que recurrir a

la ensoñación poética procedente de los estratos más profundos del

inconsciente del arquitecto. Dado que las imágenes de la materia se

sueñan de manera independiente de las formas, Bachelard ha distinguido,

en términos filosóficos, una imaginación que sustenta la causa formal

de otra, más íntima, que alimenta la causa material de modo que, en todo

hecho plástico, es necesario que una causa sentimental se convierta en

una causa formal: el arte extrae de la materia la fuerza de una acción

que se diluye en la superficie de la forma; y por ello, es posible

argumentar una ley de los cuatro elementos que clasifique las diversas

imaginaciones materiales según se vinculen a la tierra, al agua, al fuego

o al aire.

Una ley milenaria que, aunque no exclusivamente, puede rastrearse ya en

las antiguas cosmogonías presocráticas, inicio del pensamiento de los

griegos clásicos, cuya cultura tanto sedujo a Le Corbusier por estar

acostumbrados, como estaban, a significar sus ideas con belleza. Así, de

la mano de Homero4 nos llegan las primeras palabras, míticas y

poéticas que narran, emparentadas con relatos orientales, cómo en el

origen del cosmos estaba el principio húmedo bajo los nombres de Océano

y Tetis. Los físicos jónicos, con una pretensión de racionalidad,

abordaron, por primera vez fuera de la mitología, el análisis de la

estructura del mundo de la fisis. Tales, el primero de los

físicos, inicia el alejamiento del mito proponiendo como hipótesis un

monismo material según el cual todo proviene del agua; por el contrario,

Heráclito de Éfeso afirmó que en el fuego se encontraba la razón

substancial del universo y que la muerte consistía en desprenderse de ese

fuego para transformarse en humedad; y fue Empédocles quien teorizó

sobre cuatro raíces –Aristóteles las denominó elementos:

tierra, agua, fuego y aire– que aglutinaban la composición material de

la fisis.

Ahora bien, aunque esta partición del mundo parece no encerrar hoy

más que las virtudes que se desprenden de su belleza poética, su

intencionalidad filosófica encierra profundas connotaciones metafísicas.

Es cierto que los elementos no fundamentan ya ninguna teoría y que

perdieron toda su validez como paradigma positivo en el siglo XVIII, con

la aparición de la química científica de Lavoiser, sin embargo,

constituyen una clasificación de la materia, una taxonomía, cuya enorme

carga histórica y epistemológica les confiere todavía una gran eficacia

conceptual. En este sentido, las Cuatro Rutas de Le Corbusier –verdadero

programa de reformas urbanísticas para el acondicionamiento de la

macroescala geográfica– constituyen una transposición directa de la

teoría de los cuatro elementos de la naturaleza: la ruta de tierra es

milenaria, la ruta del agua es milenaria, la ruta del hierro –fuego–

tiene cien años, la ruta del aire acaba de nacer5.

El agua, como elemento, encierra en su esencia el principio de la

fluidez, explicitado tantas veces en la organización de sus plantas y

fachadas libres; es la idea de un medio particularmente fluido,

homogéneo, sereno, silencioso; una materia un tiempo cerrada e infinita

donde los cuerpos flotan, se rozan y se esquivan en un movimiento

perpetuo. El mundo del silencio imperturbable –como el que acontece bajo

las aguas profundas– es el mundo de la arquitectura sacra de Ronchamp y

de La Tourette, cuyos primeros croquis –como apunta Cyrille Simonnet–

muestran una especie de acuario, una gigantesca nave sobre pilotis que,

acaso, podría también representar un Arca de Noé depositada en una

naturaleza lavada de toda corrupción.

La imaginación mesoforma del agua, es decir, la aptitud de ésta para

componerse con los otros tres elementos, suscita también en Le Corbusier

diferentes actitudes plásticas6: la terraza-jardín, la

gárgola y la chimenea, auténticas protagonistas del lenguaje formal

corbusierano, expresan cómo sus edificios, cajas estancas, absorben o

evacuan el elemento líquido.

El agua y su elemento complementario, la tierra, dan lugar a la pasta:

un elemento viscoso portador de toda una biología. En la cubierta

ajardinada, la tierra bebe, se impregna y filtra el agua nutriéndose de

ella. El agua seminal fructifica los gérmenes depositados en la capa

terrosa y desencadena una química saludable, clorofílica,

produciendo la hierba y las flores que protegen a los usuarios del

edificio.

El agua y su elemento opuesto, el aire, originan un fenómeno de

rechazo, una corriente que brota febrilmente queriendo regresar al

paisaje. El agua surte entonces expelida por el edificio a través de un

despliegue escultórico y singular: la gárgola. Este elemento, integrado

cómodamente en su arquitectura, es la conclusión lógica de una cubierta

que Le Corbusier ha proyectado previamente como un original problema de

hidráulica. Pensemos un instante en el curioso diseño para recoger el

agua del puesto aduanero de Kembs-Nifer, situado junto al canal del

Ródano al Rin, o en las cubiertas de los palacios del Capitolio de

Chandigarh que, reelaborando la ligereza de la suspensión catenaria de la

tienda tradicional del imperio mogol, buscan la inclinación precisa para

expulsar el agua por las gárgolas estratégicamente dispuestas sobre los

estanques.

En la colina de Ronchamp, la dimensión sagrada del lugar, también

asociado a antiguos cultos paganos, proporciona una segunda metáfora: la

de la pureza del agua. Convertida ésta en un preciado bien del que no

puede desperdiciarse ni una gota, Le Corbusier la devuelve a la naturaleza

mediante un cuidadoso gesto con el que ha querido agradecer su benéfica

acción. La cubierta de la Capilla se comporta como una gran exclusa que

recoge las aguas pluviales y, como si de una libación propiciatoria se

tratase, las vierte a través de una gárgola gigante de doble tubo, en

una cisterna configurada por un curioso ensamblaje de pirámides, un

aljibe en el que Frampton7 ha querido ver un recuerdo de la

fosa excavada del mundus romano.

Finalmente, el agua y su elemento contradictorio, el fuego, originan

los vapores, evocados por el hiperboloide de la Asamblea de Chandigarh,

cuya contundente forma recuerda la de una torre de refrigeración, y

adivinados también en la plástica rotunda de los volúmenes de las

chimeneas de la Unité d’habitation de Marsella; un edificio en

el que nos detendremos para examinar otros aspectos.

De todos es conocida la célebre metáfora del palafito que recrean las

famosas villas puristas de Le Corbusier, posadas respetuosamente sobre una

naturaleza que permanece intacta. No insistiremos más; sin embargo,

analizada desde esta metáfora, la Unité de Marsella es reveladora

de una clara evolución de la sintaxis corbusierana: los esbeltos y

frágiles pilotis de la villa Savoye, asociados a las tranquilas aguas de

las construcciones lacustres, se han transformado aquí en potentes

anclajes, en musculosos soportes que, a modo de espolones, parecen

diseñados para recibir la embestida del mar o la fuerza desmedida de un

torrente fluvial. Pero si una ilusión caracteriza la obra de Marsella es

la metáfora del barco. Mucho se ha escrito sobre esta alegoría tan

querida y explotada por Le Corbusier, buscando en ella una representación

de la autonomía del lugar, la exaltación de la esencialidad de la

técnica o la fluidez con la que una embarcación se desplaza cortando los

pulsos de las olas. En este caso daremos prioridad a su singularidad

poética volviendo, de nuevo, al texto de Por las cuatro rutas. Una

de las imágenes más bellas y oníricas que ofrece este libro –similar

a la que ideó Antonioni para una escena de Desierto rojo (1964)–,

describe los navíos que surcarían el hipotético Canal de Deux-Mers

deslizándose tras los árboles, a través de los viñedos y rozando los

campos de trigo ondulados por el viento. Y en el mismo texto, pero esta

vez refiriéndose al mar, Le Corbusier se pronuncia para desvelarnos el

lirismo confinado en esta metáfora: existe una eterna poesía de los

barcos en los océanos. ¿Por qué esa emoción? Tal vez sea porque todo

el cielo está sobre nosotros, se refleja en las olas, lo envuelve todo

como una concha de nácar y azul. Tenemos esa sensación de espacio y de

materias fluidas8.

De hecho, mar y cielo son, en palabras de Valéry, los objetos

inseparables de la mirada más amplia; los más simples, los más libres

en apariencia, los más cambiantes en la entera extensión de su inmensa

unidad; y con todo, los más semejantes a sí mismos9.

Y ciertamente fueron las aguas de un mar, el Mediterráneo, el mar de

Homero y de Fidias, las que cautivaron el ánimo de Le Corbusier y

despertaron en él la sensualidad que, hasta entonces, le habían negado

las frías nieves del Jura. A lo largo de los años, me he convertido

en un hombre de mundo. He viajado a través de los continentes y, sin

embargo, no tengo más que un vínculo profundo: el Mediterráneo. Las

aguas reinas de las formas, de la luz y del espacio. El hecho concluyente

fue mi primer contacto, en 1910, en Atenas. Luz decisiva, volumen

decisivo: la Acrópolis10. Fueron también estas

aguas las que, excitadas por el sol, mudaron su primitiva acromía para

crear los colores de Grecia: los colores de Le Corbusier.

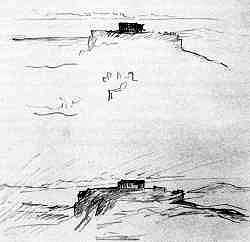

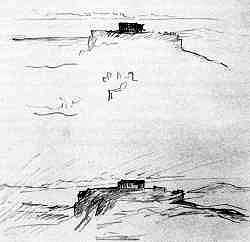

Uno de los mejores dibujos de Le Corbusier sobre la Acrópolis muestra

el Partenón recortando su silueta sobre el horizonte delimitado por las

montañas y el mar. No se trata únicamente de una representación

paisajística, sino de una poderosa intuición de la relación geométrica

fundamental que establece el templo con su entorno y a la que el maestro

recurrirá continuamente durante toda su vida. Su vertical forma con el

horizonte del mar un ángulo recto. Cristalización, fijación del

sitio. Éste es un lugar donde el hombre se detiene porque hay una

sinfonía total, magnificencia de relaciones y de nobleza. La vertical

fija el sentido de la horizontal. Una vive a causa de la otra11.

Como sabemos, el plano definido por el agua es, en la naturaleza, el

único plano perfectamente horizontal (por ello el más abstracto12)

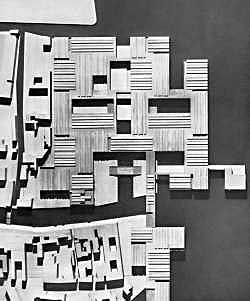

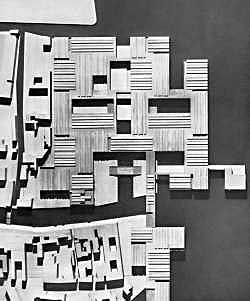

y, en sus proyectos de ciudades emplazadas junto al mar –aproximadamente

la mitad de sus trabajos urbanísticos–, define el lugar que ocupa su

centro neurálgico, la Cité d’Affaires, cuyos rascacielos

dispuestos frente al agua forman con su superficie un ángulo recto,

convirtiéndose en faros que guían la visión de los barcos al acercarse

a puerto. Barcelona, Argel, Nemours y, sobre todo, Buenos Aires, donde los

edificios se hallan literalmente sobre el agua, constituyen los mejores

ejemplos de esta relación mito-poética.

Otra gran figura alegórica del agua, la ley del meandro,

revelada azarosamente a Le Corbusier mientras sobrevolaba los principales

ríos de Brasil, fue formulada como un símbolo milagroso para

introducir sus propuestas arquitectónicas y urbanísticas de los años

treinta –¿no son acaso los meandros de los ríos los que, en sus planes

de Ville Radieuse, distinguen activamente la zonificación de la

ciudad?–. Sin embargo, la ley del meandro se puede traducir

también como una metáfora acuífera de la vida y del destino; el aforismo

sobre la verdad encerrada entre las dos orillas13 representa,

desde la percepción heracliteana, las dificultades del pensamiento

creador que, como las inevitables y vacilantes curvas formadas por la

corriente fluvial, al final, siempre encuentra la vía más natural para

abrirse paso hasta el mar.

En cierto modo relacionada con la anterior, y volviendo al contexto

mediterráneo, otra obra suya, el proyecto del Hospital de Venecia,

encierra, bajo la metáfora más evidente del impluvium de sus patios

sobre el agua, alusiones más profundas. Sobre esta ciudad Le Corbusier

escribió: Venecia es un todo. Es un fenómeno único de conservación,

de armonía total, de pureza integral y de unidad de civilización. Se ha

conservado intacta por la sencilla razón de que está construida sobre el

agua. El agua no ha cambiado y Venecia tampoco, se ha conservado entera.

[...] El agua lo rodea todo, lo defiende y paraliza al mismo tiempo14.

El Hospital es un edificio nuevo que asume sabiamente las

tipologías históricas para integrarse en la perfecta unidad de una

ciudad detenida en el tiempo, como las aguas estancadas de su laguna. Hay,

pese a su novedad, un halo fúnebre en este proyecto: las aguas muertas

son las únicas que no cambian; Venecia tampoco. La dualidad es evidente:

novedad y exquisita decadencia. Además, el Hospital es un contenedor de

funciones antitéticas: los servicios de pediatría y la capilla

funeraria, el alfa y la omega, traducen la cerrada unidad y dualidad del

agua como elemento: el continuo nacimiento que brota de las fuentes y la

inevitable muerte de los ríos que desembocan.

Continuando este recorrido por algunas de las más sugerentes

metáforas corbusieranas del agua, debemos prestar ahora una especial

atención a Chandigarh. La importancia del empleo físico de este elemento

se evidencia en el lago artificial que Le Corbusier proyecta, como

regulador climático, al prolongar el Bulevar de las Aguas, y en

las famosas albercas del Capitolio, probablemente inspiradas en los

jardines de Pinjore que el arquitecto conocía y había dibujado; sin

embargo, la presencia real del agua y los problemas de hidrografía

adquieren, en esta obra, una profunda carga simbólica. En el Capitolio,

Le Corbusier establece una agónica lucha óptica y topológica con las

dos únicas referencias físicas existentes: el dilatado plano de

asentamiento y la implacable presencia de las primeras cumbres del

Himalaya al fondo. Para rivalizar con la naturaleza, los enormes bloques

de los palacios son separados excesivamente fracturando la dimensión

antropológica de la escala. La grandiosa composición obliga a Le

Corbusier a llenar virtualmente el espacio, y para ello, intentando

corregir la excesiva distancia entre los edificios, dispone las láminas

de agua cuyas superficies duplican especularmente las arquitecturas. Ahora

bien, en el agua de los estanques no sólo aparece la imagen reflejada de

los palacios, es todo el cielo el que se mira. Parecería que les falta

a los objetos la voluntad de reflejarse. Quedan entonces el cielo y las

nubes que necesitan todo el lago para pintar su drama15...

El efecto logrado, al que suman su acción las diferencias de cota y

el modelaje de las colinas artificiales, es el contrario, pues se

acentúan las discontinuidades y rupturas, poniendo en evidencia la

desolación del Capitolio, la inmensidad de un vacío poblado de

ausencias; la soledad y el silencio cobran así connotaciones cósmicas en

el lugar.

La riqueza metafórica de las últimas obras de Le Corbusier se debe, a

juicio de William Curtis, a una confrontación entre una innovación

radical y una atracción, cada vez más poderosa, por el mundo arcaico,

instituido sobre los actos humanos fundamentales, ligados a los

elementos cósmicos: el sol, la luna, las aguas, las semillas, las

fructificaciones de la tierra16. Desde de los años treinta

y, en especial, tras la Segunda Posguerra, Le Corbusier va renunciando

paulatinamente al asidero existencial que le proporcionan las certezas de

la modernidad positivista; sometiendo a examen sus raíces culturales y

sus propios valores espirituales. El descubrimiento de la realidad india

supone para él un ejercicio de introspección que lo retrotrae al tiempo

de las verdades absolutas ya intuidas, cuarenta años antes, en el

transcurso de su iniciático Voyage d’Orient, en Atenas y

Estambul. La India penetra en su espíritu con una pluralidad de fuerzas

que provocan, inevitablemente, una convulsión en sus códigos formales.

Muy acertadamente, Tafuri ha interpretado Chandigarh como una desgarrada

gigantomaquia, donde lo que aún sobrevive de sus primeras convicciones

afronta heroicamente las figuras nacidas de la escucha de lenguas

indecibles17. En esta encrucijada cultural, Le Corbusier no

encuentra más opción que dejar hablar a la batalla y vuelca todo

su talento en la construcción de símbolos con los que entablar un

diálogo con el tiempo, la naturaleza y el ser: el árbol de la vida, la

serpiente, el trigo, la balanza de la justicia, el toro blanco de Zeus que

raptó a Pasifae en las costas de Tiro –representación dual ligada al

sol y al agua– y que es ahora el animal de Shiva, las ruedas solares,

las alegorías paganas de la luna y las mareas, la rota alquímica de las

estaciones, la mano abierta y el Modulor son algunos los iconos

intelectualizados con los que Le Corbusier enfrenta las cosmologías

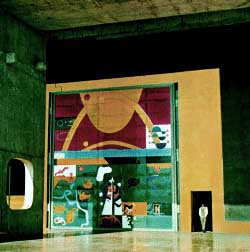

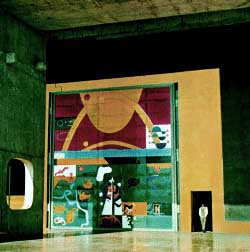

tradicionales con una metafísica contemporánea. En este sentido, La Porte

Émail18 del Palacio de la Asamblea, su último gran

trabajo pictórico, celebra el panteísmo personal del arquitecto y las

imágenes que decoran las dos caras de la puerta –la interior dedicada a

la noche y la exterior al día– ilustran los símbolos con los que ha

sido edificado el Capitolio.

La cara externa de la puerta está dividida en su mitad por la línea

del horizonte. Sobre ésta, Le Corbusier ha dibujado el cosmos con la

trayectoria ineluctable del sol en invierno y en verano, la elíptica

descrita por la tierra y la luna girando alrededor de ésta, el ritmo

cotidiano de los días con las jornadas solares de veinticuatro horas, los

esquemas de los solsticios y las curvas de los equinoccios. El lado

derecho de la pintura muestra el mundo anterior al hombre, comenzando por

el agua; dos pirámides invertidas de color amarillo19 –que

recuerdan las de la cisterna de Ronchamp– simbolizan el descenso

benefactor del agua: el vapor se condensa en forma de lluvia para originar

los cursos fluviales que se dirigen al mar. Bajo este motivo aparece un

mapa de los ríos de Europa y también el Indo y el Ganges. La extraña

perspectiva de este mural –a vista de avión pero recreada en el detalle

de los objets à reaction poétique que aparecen intercalados–

anticipa la visión que, en el espacio, los astronautas tendrán del

planeta, descrito por Le Corbusier en Précissions como un

gigantesco œuf poché donde los continentes destacan sus pliegues

y el verdor de sus bosques sobre la inmensidad de los océanos. Observada

desde este ángulo, el agua se revela como el principal órgano del mundo.

A la izquierda de la composición se representa el movimiento inverso al

del camino seguido por el agua hacia el mar; en este caso se trata de un

flujo ascendente, una especie de historia de la evolución (o proceso

alquímico) desde las más primitivas especies marinas, los moluscos y los

peces, que aparecen remontando la corriente del río, hasta el hombre,

cuya silueta se recorta sobre la línea del horizonte formando con éste

un ángulo recto. Sobre él, un águila, símbolo de la ascensión

espiritual y del eterno retorno, se eleva hacia el cielo. Las mismas

imágenes: el mar, el sol y un pájaro que ya fueron pintadas en una de

las vidrieras de Ronchamp.

De todos los motivos integrados en la puerta son los asociados al sol y

al agua los más insistentemente repetidos, y es posible descubrir los

textos aclarativos a estas imágenes en La Ville Radieuse y en el

prefacio de Précissions que anuncia el himno al sol del Poème

de l’angle droit, un libro, por otra parte, abiertamente inspirado

en el pensamiento alquímico. El interés de Le Corbusier por la alquimia

ha sido ampliamente argumentado por Frampton en su reciente monografía

sobre el arquitecto y, dada la importancia que el autor le confiere,

dedica a su estudio un capítulo entero. La filiación de Le Corbusier con

los temas herméticos donde, en la segunda mitad de su vida buscó una

fuente de motivación espiritual, queda patente en la Porte Émail pues,

uno de los principales iconos de la alquimia, el árbol de siete brazos,

ocupa en esta pintura una posición predominante convirtiéndose en el eje

sobre el que gira la puerta.

Sol y océano, fuego y agua son, para Le Corbusier, como también vimos

para los griegos, los elementos más importantes a los que se refieren los

otros dos. Aristóteles ya sostuvo que las cuatro raíces de

Empédocles no constituían principios distintos y completos en sí

mismos; poseían propiedades comunes y se podían transmutar unos en otros

a través de un proceso en el que tenía lugar un cambio cualitativo de

materia: el fuego era caliente y seco, el aire caliente y húmedo, la

tierra fría y seca, y el agua fría y húmeda. De modo que, en un nivel

más profundo, estas propiedades se reducen a dos: caliente y húmedo y

sus respectivos opuestos. El calor se debe al fuego y el frío al agua,

por tanto, al oponerse entre sí, agua y fuego son las materias

fundamentales. En alquimia, los dos elementos opuestos fuego y agua

encuentran una correspondencia directa con los dos metales básicos:

azufre y mercurio, uno combustible y el otro líquido que, a su vez,

representan los principios masculino y femenino del universo. Los antiguos

alquimistas entendieron que la fusión de estos dos principios opuestos

daba lugar a un tercero, el andrógino alquímico –tema recurrente en la

pintura corbusierana–, símbolo del triunfo del espíritu sobre la

materia a través de la gnosis, la iluminación del conocimiento.

Le Corbusier sintió instintivamente una íntima relación entre su

maniqueísta interpretación del mundo y la ancestral dualidad de la

alquimia que ilustró en el cuarto panel del Poème, Fusión,

de color rojo como el rubedo, la fase más elevada del proceso de

transmutación. Al igual que la filosofía alquímica, el pensamiento del

arquitecto operaba a través de una fuerza dialéctica que confrontaba

términos opuestos interdependientes. En los elementos antagónicos

fuego-agua, azufre-mercurio, sol-océano, se encuentra un paralelismo con

las parejas de conceptos polares naturaleza-cultura, racional-irracional,

máquina-vida, Apolo-Medusa, ortogonal-orgánico, vertical-horizontal,

arquitecto-ingeniero, día-noche que, valorándose recíprocamente en su

oposición, sustentan la dualidad en la que se movía el discurso

corbusierano. Incluso, Frampton ha querido ver en el posible suicidio de

Le Corbusier en Cap-Martin el cumplimiento de un sueño y de una profecía

del arquitecto: la sublimación final del cuerpo en el elemento

femenino del océano nadando hacia el sol masculino.

Pero además, la principal figura dicotómica de la tradición

alquímica es Mercurio, sabio portador de sus secretos y legendario

fundador de la vía hermética cuyo atributo más representativo –ha

reparado Frampton–, el caduceo, la vara donde se entrelazan dos

serpientes, resurge inquietantemente en el Hombre-Modulor de Le Corbusier.

Las referencias que tenemos de este demiurgo nos lo presentan bajo dos

encarnaciones sucesivas: como señor del mundo subterráneo y como principio

aéreo desmaterializado que se eleva desde la tierra al cielo y vuelve a

descender en el curso del mismo ciclo para unir, según dicta el

célebre aforismo hermético, lo que está arriba con lo que está debajo.

Así, extendiendo aún más estos paralelismos, percibimos que las

imágenes del agua descritas en la Porte Émail tienen mucho en

común con el ciclo del aqua mercurialis; el ciclo acuoso de la

vida o movimiento continuo del agua en la atmósfera y en la tierra que,

dado que la cantidad de agua existente en el planeta se mantiene

prácticamente constante, supone un eterno ascenso y descenso fruto de la

interacción entre el sol y el océano. En La Ville Radieuse, Le

Corbusier expresa:

He aquí un día de 24 horas bien lleno, variado, admirable y

benefactor. La noche: todo duerme. El agua, infinitamente repartida, lleva

a cabo su gesto caritativo: todo está empapado. 4 horas: el sol aparece

al borde de la llanura; el rocío está sobre las hierbas, en el hueco de

cada hoja. Habiéndose marchado el sol ayer por la tarde, el frescor ha

hecho gotas sobre la tierra de lo que no era más que vapor de agua en el

aire. 8 horas: el rocío abandona la tierra, el sol levantado llama al

agua [...] Mediodía: la hora del sol glorioso. Sus flechas golpean

directas el suelo y encienden hogueras [...] 17 horas: estalla el

relámpago, seguido de inmensos truenos. Todo es terror, trombas de agua;

la oscuridad rodea este desencadenamiento. Los animales tienen miedo [...]

18 horas: la tierra está empapada. El cielo es límpido. El sol se

recorta, se aproxima al horizonte [...] Dos elementos han jugado juntos el

juego magnífico: lo masculino, lo femenino. Sol y agua.

La metáfora dual del aqua mercurialis se revela extremadamente

fecunda para Le Corbusier puesto que a la unión agua-fuego, sexualizados

en su oposición, se añade la ambivalencia del elemento líquido que se

desdobla a su vez en parejas de términos contrarios: el agua es un

símbolo maternal pero deja de ser femenina y cambia de sexo cuando se

torna violenta; el agua es una vigorosa corriente que no cesa pero

también inmovilidad y silencio cuando se hace profunda; el agua es fuente

continua de vida pero también representa la muerte de todas las cosas que

vuelven a ella...

En julio de 1965, Le Corbusier redactó Rien n’est transmissible

que la pensée, el último de sus textos. Escrito a modo de

despedida del mundo, con la lucidez que aporta una serena madurez, su

testamento intelectual contiene una reflexión sobre la continuidad,

regularidad y perseverancia indispensables en toda creación artística y

también un juicio retrospectivo sobre la naturaleza ineludible de la

existencia –fugaz como un vértigo, a cuyo término se llegará sin

darse cuenta–. Una vez más, el maestro ha querido ver la imagen del

destino individual del ser humano en el destino implacable de las aguas. Mirad,

pues, la superficie de las aguas [...] Mirad también el azul, lleno del

bien que los hombres hayan hecho [...], porque al final todo retorna al

mar.

Un mes más tarde, el 27 de agosto, sucumbía a una crisis cardiaca

cuando se bañaba en el Mediterráneo. Le Corbusier desaparecía en este

elemento marino, fundamental para él, cuyas aguas representaban la

mesura, la pureza, la armonía y la permanencia, tanto de la forma y del

espacio como del pensamiento y del espíritu20.

|

As

we look closer at the drawings for A. de la Sota’s recreational homes in Alcudia, we

find a series of cons

A critical approach to the work of Le Corbusier requires the

construction of diagonal readings to correct the inevitable deformations

concerning his personality and architectural discourse that excessively

specialised discipline-bound research has created. A rigorous approach to

his intense intellectual career, often full of insecurities and paradoxes,

means viewing his busy life as an incessant creative activity devoted to

revealing the encoded reality hidden under the forms. As Gregotti1

noted, no gesture in his work seems to have been decided for purely

aesthetic reasons. To Le Corbusier, inventing meant solving a problem,

converting the form into a crucible of questions, an amalgam of

heterogeneous experiences, in the necessary conclusion to a continuous

search and dense reflection that took complex materials as the starting

point on which to found the ideas that structure the project.

Metaphors are one of the most interesting of these materials. Le

Corbusier’s recourse to metaphors is not a superficial excuse but comes

from the profound nature of his observation of things. Metaphor is the

medium that binds together images that partake of both the rational and

the irrational, which emerge from a hyper-sensitive, permeable, poetic

spirit forged by various cultures. For this reason Le Corbusier’s later

metaphors are undoubtedly the most fertile but are also the most

difficult: as time passed they became increasingly opaque and hermetic as

the architect assimilated the multiple influences offered by the different

places he visited. Through metaphor his works ring the changes on such

diverse combinations as machinist slogans and enchanting literary figures,

unusual surrealist echoes and the most ancient voices of the Mediterranean

civilisations or even the dualism of alchemical thought and the immemorial

cosmic myths of Indian religions2.

His architectural forms cannot be fully explained without giving due

importance to this device; they might even appear senseless if the

inexhaustible potential contained in the expressive ambiguity of this

trope is omitted. It is therefore essential to resort to his writings and,

above all, his painting (he himself never tired of repeating that this was

where the secret of his architecture lay) to discover valuable keys which

provide access, or more complete access, to the inexhaustible teachings of

his most brilliant and enigmatic works in the constant flow of allegories

and metaphors that fed his imaginary world.

We may therefore propose a study of water in the work of Le Corbusier,

as the material that inspired many of his principal metaphors. In this

sense we would be talking about a medium for images or, as Gaston

Bachelard3 defined it, a metapoetics of water. It is not a

matter of recognising a particular group of vague and possibly unconnected

images but of identifying the unity of the element, water, as the

principle on which they are founded. In order to define this task, we must

resort to the poetic fantasy that rose out of the deepest layers of the

architect’s unconscious. Since images of matter are dreamed

independently from those of forms, Bachelard distinguished, in philosophic

terms, an imagination which sustains the formal cause of another, more

intimate imagination which feeds the material cause in such a way that a

sentimental cause must be converted into a formal cause in every plastic

act: art extracts from matter the force of an act that is diluted in the

surface of the form; it is therefore possible to argue for a law of the

four elements that classifies the diverse material imaginations according

to whether they are linked to earth, water, fire or air.

This age-old law can be traced back as far as, although it is not

exclusive to, the ancient pre-Socratic cosmogonies that led to the

thinking of the classical Greeks, whose culture so seduced Le Corbusier

because they were accustomed to signifying their ideas with beauty. The

first mythical and poetic words, related to oriental tales, that tell us

how the moist element was present at the origin of the cosmos under the

names of Ocean and Thetis have come down to us through the works of Homer4.

The Ionian physicists, in their desire for rationality, were the first to

embark on analysing the structure of the world of phusis without

referring to mythology. Thales, the first of the physicists, began the

departure from myth by proposing the hypothesis of a material monism where

everything had its origin in water. Heraclitus of Ephesus, on the other

hand, affirmed that the substantial reason of the universe was to be found

in fire and that death consisted of parting with this fire and becoming

moisture. It was Empedocles who postulated the theory of four roots –

and Aristotle who called them elements: earth, water, fire and air –

that combined to form the material composition of the phusis.

However, although the only virtue that this partition of the world

holds for us nowadays appears to be the results of its poetic beauty, its

philosophic intention has profound metaphysical connotations. It is true

that the elements are no longer the foundation of any theory, as they lost

all validity as a positive paradigm when Lavoiser’s scientific chemistry

appeared in the 18th century. However, they constitute a

classification of matter, a taxonomy, with an enormous historical and

epistemological charge that still imbues them with great conceptual

efficacy. In this sense, Le Corbusier’s Four Roads (a true

programme of town planning reform for equipping the geographic

macro-scale) constitutes a direct transposition of the theory of the four

elements of nature: the route of earth is age-old, the route of water

is age-old, the route of iron (fire) is a hundred years old, the

route of air has just been born5.

Water, as an element, contains in its essence the principle of fluidity

that was so often explicit in the organisation of his floor plans and free

façades. It is the idea of a particularly fluid, homogeneous, serene,

silent medium, a material that is at the same time closed and infinite in

which bodies float, brushing past and avoiding each other in perpetual

motion. The world of imperturbable silence, like that which lies beneath

the deep waters, is that of the religious architecture of Ronchamp and La

Tourette. As Cyrille Simonnet pointed out, the first sketches for these

buildings show a kind of aquarium, a giant nave on pilotis that might

perhaps also represent a Noah’s Ark deposited on a natural world washed

free of all corruption.

The mesoform imagination of water, in other words its gift for

combining with the other three elements, also gives rise in Le Corbusier

to different plastic attitudes6: terrace-gardens, gargoyles and

chimneys, authentic protagonists of his formal language, express the ways

in which the hermetic boxes of his buildings absorb or evacuate the liquid

element.

Water and its complementary element, earth, combine to form a paste, a

viscous element that carries an entire biology within it. On the roof

garden the earth drinks, soaks up and filters the water, drawing nutrition

from it. The seminal water brings the germs deposited on the layer of

earth to fruit and unleashes a healthy, chlorophyll chemistry that

produces the grass and flowers which protect the building’s users.

Water and its opposite element, air, set up a phenomenon of rejection,

a flow that spouts out feverishly in its desire to return to the

landscape. In this case the water is expelled by the building through a

singular sculptural display: the gargoyle. This feature, comfortably

integrated into his architecture, is the logical conclusion of a roof that

Le Corbusier had already designed as an original hydraulic problem. Let us

consider for a moment the curious design to collect the water at the

customs post of Kembs-Niter, next to the Rhone-Rhine canal, or the roofs

of the palaces in Chandigarh’s Capitol complex which, reworking the

lightness of the cable suspension in the traditional tents of the Moghul

empire, seek the precise slope required to expel the water through the

gargoyles strategically placed over the ponds.

On the Ronchamp hill the sacred dimension of a place that was also

associated with ancient pagan religions provides a second metaphor, that

of the purity of water. Water becomes a precious good of which not a

single drop must be wasted. Le Corbusier returns it to nature with a

careful gesture intended to offer thanks for its beneficial actions. The

roof of the Chapel acts as a great lock, collecting the rainwater and

pouring it like a propitiatory libation through a giant double-pipe

gargoyle into a tank made up of a curious assembly of pyramids, a

reservoir in which Frampton7 has seen a reminder of the

excavated pit of the Roman mundus.

Finally, water and its contradictory element, fire, give rise to

vapour, evoked by the hyperboloid of the Assembly in Chandigarh. Its

emphatic form recalls that of a refrigeration tower. They can also be

divined in the robustly plastic volumes of the Unité d’habitation chimneys

in Marseilles. Let us pause to examine other aspects of this building.

Everyone knows the celebrated metaphor of the stilt house recreated by

Le Corbusier’s famous purist villas, respectfully set down in natural

surroundings that remain intact. No more need be said, but if the

Marseilles Unité is analysed in terms of the same metaphor it

reveals a clear evolution of Le Cobusier’s syntax: the slim, fragile

pilotis of the Villa Savoye, associated with the quiet waters of lake

buildings, are here transformed into powerful anchors, muscular supports

that seem to be designed like breakwaters to withstand the fury of the sea

or the excessive force of a mountain torrent. However, if there is one

illusion that typifies the Marseilles building it is the metaphor of a

boat. Much has been written about this allegory that Le Corbusier loved

and used so much. It has been read as a representation of the autonomy of

the place, an exaltation of the essentiality of the technique or of the

fluidity with which a boat moves, cutting though the pulsing waves. Here

we will give priority to its poetic singularity and come back once more to

The four roads. One of the most beautiful and dream-like images in

this book, similar to that which Antonioni thought up for a scene in Red

Desert (1964), describes the boats that would cleave the waters of the

hypothetical Canal de Deux-Mers, slipping behind the trees and

between the vineyards and brushing by the fields of wheat rippling in the

wind. In this same text, this time referring to the sea, Le Corbusier

reveals the lyrical quality this metaphor encloses: there is an eternal

poetry in ships on the oceans. What is the reason for this emotion? It may

be because all the sky is above us, it is reflected in the waves, it wraps

around everything like a blue and mother-of-pearl shell. We have this

feeling of space and of fluid materials8.

Indeed, in the words of Valéry, sea and sky are the inseparable

objects of the widest gaze; the simplest, the most free in appearance, the

most changing in the entire extension of its immense unity; even so, they

are the ones that most resemble each other9.

It was certainly the waters of a sea, the Mediterranean, the sea of

Homer and of Phidias, that captivated the spirit of Le Corbusier and

aroused the sensuality that the cold snows of the Jura had hitherto denied

him. Over the years I have become a man of the world. I have travelled

over the continents yet I have only one deep tie: the Mediterranean. Its

waters are queen of forms, of light and of space. The decisive event was

my first contact, in 1910, in Athens. Decisive light, decisive volume: the

Acropolis10. It was also these waters, excited by the sun,

that changed his original achromatism and created the colours of Greece,

the colours of Le Corbusier.

One of Le Corbusier’s best drawings of the Acropolis shows the

Parthenon in silhouette against a horizon bounded by the mountains and the

sea. It is not just a landscape drawing but rather a powerful intuition of

the basic geometrical relationship of the temple with its surroundings

that the master constantly turned to throughout his life. Its vertical

form and the horizon of the sea form a right angle. Crystallisation,

fixation of the site. This is a place where a man stops because there is

total harmony, a magnificence of relations and of nobility. The vertical

establishes the meaning of the horizontal. The one lives because of the

other11. As we know, the plane defined by the water is the

only perfectly horizontal plane in nature (and therefore the most abstract12).

In Le Corbusier’s projects for cities beside the sea (about half of his

town planning work) it defines the place to be occupied by their neuralgic

centre, the Cité d’Affaires. The skyscrapers are laid out along

the sea and form a right angle with its surface, becoming lighthouses that

guide the view from the boats as they approach the port. Barcelona,

Algiers, Nemours and, above all, Buenos Aires, where the buildings are

literally on the sea, are the best examples of this mythical-poetic

relationship.

Another great allegorical figure of the water, the law of meander,

was revealed to Le Corbusier by chance as he flew over the main rivers of

Brazil. He formulated it as a miraculous symbol with which to

introduce his architectural and town planning proposals of the thirties

(do not river meanders actively distinguish the zoning of the city in his

plans for the Ville Radieuse?). However, the law of meander

can also be interpreted as an aquiferous metaphor for life and destiny: in

Heraclitus’ perception the aphorism of the truth contained between

the two banks13 represents the difficulties of creative

thinking which, like the inevitable meandering curves formed by the

currents of the river, eventually always encounters the most natural path

by which to make its way to the sea.

Related in a way to the above but returning to the Mediterranean,

another of his works, the project for the Venice Hospital, contains more

profound allusions under the more obvious metaphor of the impluvium of its

courtyards over the sea. Le Corbusier wrote of this city: Venice is a

whole. It is a unique phenomenon of conservation, of total harmony, of

integral purity and of unity of civilisation. It has preserved itself

intact for the simple reason that it is built on water. The water has not

changed and neither has Venice, it has preserved itself entire. [...] The

water surrounds everything, it defends and paralyses it at one and the

same time14. The Hospital is a new building that wisely

accepts the historical typologies in order to integrate itself into the

perfect unity of a city stopped in time, like the stagnating waters of its

lagoon. Despite its novelty there is a funereal aura to this project: dead

waters are the only ones that do not change; neither does Venice. The

duality is obvious: novelty and exquisite decadence. Moreover, the

Hospital is a container for antithetical functions: the paediatric

services and the funeral chapel, alpha and omega, transcribe the closed

unity and duality of the water as an element: the continuous birth that

bubbles from the springs and the inevitable death of the rivers as they

reach the sea.

To continue this look at some of Le Corbusier’s most

thought-provoking water metaphors, particular attention must be paid to

Chandigarh. The importance of the physical use of this element is shown by

the artificial lake that Le Corbusier designed to regulate the climate

when he prolonged the Boulevard of the Waters and by the famous

reservoirs of the Capitol. These were probably inspired by the Pinjore

gardens, which the architect knew and had drawn. However, the real

presence of the water and the hydrographic problems acquire a profound

symbolic charge in this work. In the Capitol Le Corbusier set up an

optical and topographical fight to the death with the only two existing

physical reference points: the extensive plane of the site and the

implacable presence of the first peaks of the Himalayas in the background.

In order to rival nature, the enormous blocks of the palaces are separated

excessively, fracturing the human dimension of the scale. This grandiose

composition obliged Le Corbusier to fill the space virtually and he

therefore tried to correct the excessive distance between the buildings by

laying out sheets of water with surfaces that duplicate the architecture

as though in a mirror. However, it is not only the reflected image of the

palaces that appears on the water of the pools but the whole sky that is

seen there. It would seem that the objects lack the will to be

reflected. What is left, then, is the sky and the clouds, which need the

whole lake on which to paint their drama15 ... The effect,

augmented by the differences in level and the modelling of the artificial

hills, is the contrary: the discontinuities and ruptures are accentuated

and demonstrate the desolation of the Capitol, the immensity of an empty

space peopled by absences; solitude and silence thus acquire cosmic

connotations in this place.

The metaphorical richness of Le Corbusier’s last works is due, in

William Curtis’ opinion, to a confrontation between radical innovation

and an increasingly powerful attraction to the archaic world, based on fundamental

human acts linked to the cosmic elements: the sun, the moon, water, seeds,

the earth bearing fruit16. From the thirties onwards,

particularly after the Second World War, Le Corbusier gradually

relinquished the existential crutch provided by the certainties of the

positivist modern movement and subjected his cultural roots and his own

spiritual values to scrutiny. His discovery of the Indian reality became

an exercise in introspection that took him back in time to the absolute

truths of which he had already had a intuition forty years earlier, in

Athens and Istanbul, on his initiatory Voyage d’Orient. India

penetrated his spirit with a plurality of forces that inevitably caused a

convulsion in his formal codes. Tafuri has quite rightly interpreted

Chandigarh as a heartrending struggle of giants where what still survived

of his first convictions heroically squared up to the figures born from

listening to indescribable languages17. At this cultural

crossroads Le Corbusier encountered no option other than to let the

battle speak and poured all his talent into building symbols with

which to enter into a dialogue with time, nature and being: the tree of

life, the serpent, wheat, the scales of justice, the white bull in whose

form Zeus abducted Europe on the coasts of Tyre (a dual representation,

linked to both water and the sun) which is now Shiva’s animal, sun

wheels, pagan allegories of the sun and the tides, the alchemist’s round

of the seasons, the Open Hand and the Modulor are some of the

intellectualised icons by which Le Corbusier confronts the traditional

cosmologies with a contemporary metaphysics. From this point of view the Porte

Émail 18

of the Assembly, his last great pictorial work, celebrates the

personal pantheism of the architect and the images that decorate the two

sides of the door, the interior dedicated to night and the exterior to

day, illustrate the symbols with which the Capitol was built.

The outer side of the door is divided in two by the line of the

horizon. Above it Le Corbusier drew the cosmos with the ineluctable course

of the sun in winter and in summer, the ellipsis traced by the earth and

the moon revolving around it, the daily rhythm of the days and the

twenty-four hours of the solar day, the patterns of the solstices and the

curves of the equinoxes. On the right hand the painting shows the world

before mankind, starting with water. Two inverted yellow- coloured

pyramids19 – reminiscent of those of the Ronchamp cistern –

symbolise the beneficent descent of the water: vapour is condensed into

rain and gives rise to the paths of the rivers that run towards the sea.

Under this motif there is a map of the rivers of Europe and of the Indus

and the Ganges. The strange perspective of this mural – as seen from an

aeroplane but recreated in the details of the interspersed objets à

reaction poétique – is an anticipation of the view of the planet

from space that astronauts would have, described by Le Corbusier in Précisions

as a giant oeuf poché where the folds of the continents and

the green of their woods are highlighted on the immensity of the oceans.

Observed from this angle, water is revealed as the main organ of the

world. On the left of the composition the opposite movement to that of the

river making its way to the sea is represented. Here it is an ascending

flow, a kind of history of evolution (or alchemical process) from the most

primitive marine species, molluscs and fishes, which are seen swimming

upstream, to man, whose silhouette stands out on the line of the horizon,

forming a right angle between them. Above the man an eagle, symbol of

spiritual ascent and eternal return, rises up into the sky. The same

images: the sea, the sun and a bird, that had already been painted on one

of the Ronchamp windows.

Of all the motifs woven into the door those associated with the sun and

water are the most insistently repeated. The texts that clarify these

images can be discovered in La Ville Radieuse and in the preface to

Précisions that foreshadows the hymn to the sun in the Poème

de l’angle droit, a book that was clearly inspired by alchemical

thinking. Le Corbusier’s interest in alchemy was discussed extensively

by Frampton in his recent monograph on the architect: he attaches such

importance to it that he devotes an entire chapter to studying this

subject. Le Corbusier’s leaning towards hermetic subjects, in which he

sought a source of spiritual motivation in the second half of his life, is

patent in the Porte Émail and one of the main icons of alchemy,

the seven-branched tree, occupies a predominant position in this painting,

becoming the axis around which the door revolves.

For Le Corbusier, as they had been for the Greeks before, sun and

ocean, fire and water were the most important elements, to which the other

two refer. Aristoteles already held that Empedocles’ four roots

were not distinct and complete in themselves but had common properties and

could change into each other by a process in which a qualitative change in

material took place. Fire is hot and dry, air hot and wet, earth cold and

dry and water cold and wet. As a result, at a deeper level, the principles

are reduced to the two properties of hot and wet and their opposites. Heat

is due to fire and cold to water. Therefore, as each other’s opposites,

water and fire are the fundamental materials. In alchemy the two opposite

elements, fire and water, correspond directly to the two basic metals,

sulphur and mercury, the one combustible and the other liquid. These in

turn represent the male and female principles of the universe. The old

alchemists understood that the fusion of these two opposite principles

gave rise to a third, the alchemical hermaphrodite – a recurring theme

in Le Corbusier’s painting – which symbolises the triumph of spirit

over matter through gnosis, the enlightenment of knowledge.

Le Corbusier instinctively felt an intimate link between his Manichean

interpretation of the world and the ancestral duality of alchemy that he

illustrated in Fusion, the fourth panel of the Poème, which

is red like the rubedo, the highest stage in the process of

transmutation. As in alchemical philosophy, the architect’s thinking

worked through a dialectic force that brought interdependent opposite

terms face to face. There is a parallel between the opposing elements of

fire-water, sulphur-mercury, sun-ocean and the pairs of conceptual poles

nature-culture, rational-irrational, machine-life, Apollo-Medusa,

orthogonal-organic, vertical-horizontal, architect-engineer, day-night:

reciprocally drawing value from their opposition, they sustain the duality

in which Le Corbusier’s discourse moved. Frampton has even interpreted

Le Corbusier’s possible suicide at Cap-Martin as the fulfilment of a

dream, prophesied by the architect: the final sublimation of the body

in the female element of the ocean swimming towards the male sun.

This is not all. The main dichotomic figure in the alchemical tradition

is Mercury, the wise carrier of secrets and legendary founder of the

hermetic way. His main symbol, the caduceus, the wand with two serpents

wound around it, reappears disquieteningly in Le Corbusier’s

Modulor-Man, as Frampton noted. The references we have to this demiurge

show him in two successive incarnations: as lord of the underground world

and as dematerialised airy principle that rises from the earth into the

sky and back downwards in the course of the same cycle in order to

unite what is above with what is below, as the famous hermetic aphorism

dictates. Consequently, extending these parallels still further, we see

that the images of water in the Porte Émail have much in common

with the cycle of the aqua mercurialis; the watery cycle of life or

continuous movement of water in the atmosphere and the earth which - since

the quantity of water that exists on the planet remains practically

constant - involves an eternal rise and fall as a result of the

interaction between the sun and the ocean. In La Ville Radieuse Le

Corbusier says:

Here is a 24-hour long day, packed, varied, admirable, beneficent. At

night everything is asleep. The water, infinitely shared out, performs its

charitable gesture: everything is drenched. At 0400 the sun appears on the

edge of the plain, the dew is on the grass, in the hollow of each leaf.

Since the sun went away yesterday afternoon the coolness has made drops on

the earth out of what was no more than water vapour in the air. At 0800

the dew abandons the earth, the sun is up and calls the water away [...]

Midday is the hour of the glorious sun. Its arrows strike the ground

directly and light bonfires [...] At 1700 the lightning breaks out,

followed by immense thunderclaps. Everything is terror, downpours: the

darkness surrounds this unleashing. The animals are afraid [...] At 1800

the earth is drenched. The sky is clear. The sun is silhouetted as it

approaches the horizon [...] Two elements have played the magnificent game

together: male and female. Sun and water.

The dual metaphor of the aqua mercurialis reveals itself to be a

very fertile one for Le Corbusier as the union of water and fire,

sexualised in their opposition, is joined by the ambivalence of the liquid

element, which also doubles up into pairs of opposites: water is a

maternal symbol but ceases to be female and changes sex when it becomes

violent; water is a vigorous unceasing current but is also stillness and

silence when it is deep; water is the continuous spring of life but also

represents the death of all the things that return to it...

In July 1965 Le Corbusier wrote the last of his texts, Rien n’est

transmissible que la pensée. Written as a kind of farewell to the

world, with the lucidity conferred by serene maturity, his intellectual

testament contains a reflection on the continuity, regularity and

perseverance that are indispensable to all artistic creation as well as

looking back over the inescapable nature of existence, as fleeting as a

dizzy turn, its end reached without noticing. Once again the master

saw the image of the individual destiny of the human being in the

implacable destiny of the waters: Look, then, at the surface of the

waters [...] Look also at the blue, full of the good that men have done

[...], because in the end everything returns to the sea.

A month later, on 27th August, Le Corbusier died of a heart

attack while bathing in the Mediterranean. He disappeared into the marine

element that was so essential for him, whose waters represented measure,

purity, harmony and permanence, both of form and space and of the mind and

spirit20. |

|

|