|

En el puerto de la ciudad marítima se produce una

confrontación de escalas: la territorial; la de la ciudad; la del lugar.

Cada una aporta su lógica propia para configurar un paisaje singular y

único. Hay otra escala: la del mar, de imposible medida como lo son los

caminos invisibles que lo surcan. Caminos en los que sólo se hace visible

su principio y su final: el puerto.

La escala territorial del puerto está presente por su

condición de nodo de un sistema de comunicaciones terrestres, carreteras

y ferrocarriles, que constituyen el campo de acción del interland

portuario. Estas líneas de transporte se trazaron buscando el puerto,

dando forma al territorio, y penetrando en la ciudad contribuyeron

también a darle forma al espacio urbano. Como escribió Braudel, el gran

historiador del Mediterráneo:

Ciudades y rutas, rutas y ciudades forman un solo y

único aspecto del equipo humano del espacio. Cualesquiera que sean su

forma, su arquitectura o la civilización que la ilumine, la ciudad

mediterránea es siempre hija del espacio, creadora de rutas y, al mismo

tiempo creada por ellas.

No se puede explicar la ciudad portuaria sin el puerto,

con el que ha tenido, y tiene, una estrecha relación social y económica.

No se puede entender la fachada marítima de la ciudad portuaria sin el

puerto que la identifica y le da forma, relación más intensa a medida

que lo es la inserción física de ciudad y puerto, como ocurre en

Barcelona, Alicante, Almería o Málaga entre otras ciudades

mediterráneas.

El puerto como lugar aporta toda su carga de

significados. Como decía el ingeniero José A. Fernández Ordóñez: Desde

tiempo inmemorial, por medio de las obras públicas, el hombre configura

el espacio y se apropia de él, lo señala y significa, creando un lugar

en sentido heideggeriano. El puerto es un lugar de límites, y el

límite crea lugar y arquitectura. Como límite entre la tierra y el mar,

y como límite que imponen al mar las geometrías de las dársenas y

diques, el puerto se configura como una arquitectura donde los muelles

constituyen el edificio y las dársenas el negativo donde el mar se

amansa.

El puerto impone un límite a la naturaleza, un orden a

la ribera, es una puerta entre un interior conocido y un exterior

desconocido. Nadie mejor que Eduardo Chillida ha sabido interpretar toda

la tensión simbólica y poética que se oculta en el límite entre la

tierra y el mar en su Peine del Viento de San Sebastián. Como él mismo

decía:

¿Y que es lo que definía el sitio del Peine del

Viento?. En primer lugar una reflexión fundamental para cualquiera que

emprenda la tarea de intervenir en el borde costero: su realidad

dialéctica. La costa es, al mismo tiempo, principio y fin de un

territorio, de una ciudad... En ese lugar ocurrían cosas muy elementales:

Estaba el horizonte allí detrás, la existencia del mar con su lucha,

estaban los hombres arrimándose a mirar lo desconocido desde lo pasado

hasta hoy, que seguimos mirando sin saber lo que hay detrás.

En su devenir histórico, la continuidad espacial y

morfológica de la ciudad y el puerto se fracturó. El puerto

mediterráneo moderno, que surge en torno a la mitad del siglo XIX,

comienza a separarse de la ciudad, erigiéndose en un paisaje autónomo

construido desde una lógica funcional.

Sometido a los avatares de los cambios impuestos por

las innovaciones técnicas que intervienen en su propia construcción,

así como en el transporte marítimo; pero también bajo las

transformaciones culturales que dirigen el imaginario de los ciudadanos,

el puerto irá acumulando toda esa experiencia exterior e interior en las

miradas de los que lo contemplan.

Las intervenciones de cambio de uso sobre antiguos

espacios portuarios españoles, operaciones tan frecuentes desde los años

90 del siglo que acaba de terminar, debían de haber recogido todo ese

caudal de memoria e imaginario en torno al mar incorporándolo a la forma

y al significado de los nuevos espacios y arquitecturas portuarias en un

dialogo entre lo intemporal del mar y la memoria de los hombres que reúne

a obras tan separadas por el tiempo como el templo griego de Sunión y el

cementerio de Cesar Portela en Finisterre.

I

Gastón Bachelard sostiene que la imaginación no es la

facultad de formarse imágenes de la realidad, esto constituye el mundo de

lo percibido, para él la imaginación construye imágenes de lo

invisible. De ese modo el imaginario perceptivo se modifica al estar

influido por los cambios culturales, mientras ese otro imaginario- que

Bachelard llama creativo- pertenece al interior del alma humana y

hunde sus raíces en los orígenes remotos de nuestra cultura. En este

sentido, el filósofo francés nos propone una interpretación del paisaje

muy diferente del fundado en la representación, como escribe en El

Agua y los Sueños: La atracción del paisaje es un amor que esta fundado

en otra parte. Materias como el agua desencadenan un imaginario que

tiene su origen en un fondo humano primigenio.

Sin embargo para Bachelard, el agua del mar y el agua

dulce inducen distintos imaginarios. El agua dulce de una fuente o de un

lago, nace o crece, tiene forma y memoria; en cambio el mar no tiene ni

forma ni memoria: ambas se las da el puerto.

El agua dulce es la verdadera agua mítica, escribe

Bachelard, pero añade que el agua del mar tiene también su propia

mitología pero enraizada mas en el relato que en la materia: la

primera experiencia del mar pertenece al orden de los relatos, dice en

la obra citada.

Sin embargo la lamina de agua de las antiguas dársenas

portuarias mediterráneas construidas desde mediados del siglo XIX nos

remiten a un lago cuyo espejo de agua refleja la ciudad y la duplica. La

lamina de agua portuaria de este puerto decimonónico se configura por una

estructura de dos diques, uno a levante y otro, el contradique, a

poniente. Este modelo es muy común en puertos como Tarragona, Alicante,

Almería y Málaga.

Esta gran lámina de agua que aparece frente a la

ciudad constituirá un verdadero acontecimiento para los ciudadanos, y

excitará sus emociones e imaginario. Como debió de ocurrir en Alicante

donde, en el último tercio del siglo XIX, se abre la gran dársena

interior del puerto que con una dimensión de 24 Has. podría acoger

dentro de ella la practica totalidad de la ciudad construida en aquel

momento.

La dársena del puerto decimonónico se convierte en un

espectáculo siempre diferente. El puerto es un lugar donde se mira, es

una escena de arquitecturas efímeras sobre el límite fijo de muelles con

sus cantiles de geometrías rotundas. Como ha escrito Alain Corbin:

El paseo a lo largo de los muelles y malecones, que

se perpetuará bajo formas renovadas, expresa la fascinación ejercida por

una escena en que se despliegan, con especial evidencia, el entusiasmo, la

actividad, el heroísmo y el infortunio. Escena que se integra con toda

lógica en el viaje clásico. Ahora, la naturaleza ha reculado ante el

trabajo del hombre, que ha modelado la piedra, rehecho los limites

asignados por Dios al océano.

El paisaje portuario mediterráneo construido sobre un

suelo artificial de muelles y dársenas se completará con el equipamiento

arquitectónico y de maquinaria para la carga y descarga durante el

periodo comprendido entre los 80 del XIX y los 30 del XX. Tinglados,

depósitos y grúas darán los signos identificadores y diferenciadores

del nuevo paisaje. Un paisaje industrial cada vez mas separado de la

ciudad a medida que la naturaleza de las operaciones portuarias lo hacen

incompatible con la ciudad.

Sin embargo los habitantes de la ciudad portuaria

verán ese paisaje industrial como una fuente de riqueza y bienestar

material presente, tanto en el ir y venir de los veleros y vapores, como

en las humeantes máquinas de vapor que circulan junto a los primeros

paseos marítimos, como la Explanada de Alicante, proyectada por

ingenieros portuarios en torno a 1916.El puerto moderno, como un puente de

hierro o la Estación de Ferrocarril, es un potente inductor de imaginario

de progreso, un sentimiento que ligaba, en las mentalidades

decimonónicas, los avances técnicos con el cambio moral y la esperanza

de la humanidad.

La época en que se inaugura la construcción del

puerto moderno congrega otras miradas sobre el mar y sus riberas que no se

mira como lugar de marismas, origen de miasmas transmisoras de

enfermedades, sino que se descubren las cualidades terapéuticas del agua

del mar, lo que dará lugar a la extensión de los baños de mar.

El puerto resume toda esta nueva cultura sobre el mar.

El puerto moderno mediterráneo se construye sobre diques que penetran en

el mar como brazos protectores; diques que se cosen a la ciudad,

asimilando el puerto a una prótesis que se impone a la línea de costa

resolviendo la impotencia de los hombres frente a la naturaleza. Como ha

dicho Gómez de Liaño:

Toda ciudad costera es una ciudad seccionada, con un

mar que la corta y la aprieta a la tierra, al mismo tiempo que la lanza y

efunde por las mil rutas marinas. El puerto con sus tinglados, pasos

aduaneros, muelles, que enchufan como clavijas, a la tierra con el mar, el

puerto, digo, es la puerta-como el ponto es el puente- que comunica la

ciudad visible con una ciudad invisible fantástica, que siempre es

lejana, próxima, igual y distinta, y que se construye discontinuamente a

golpes de apariciones.

II

Las arquitecturas portuarias del puerto moderno fueron

proyectadas por Ingenieros de Caminos que habían tenido una formación

arquitectónica en la Escuela del Cuerpo en la que confluía el

conocimiento de la obra de J.N.L.Durand-Su Précis fue texto de la

asignatura Arquitectura desde mediados del siglo XIX-con el de los

lenguajes historicistas y eclécticos de finales de ese siglo. En

consecuencia esa arquitectura es de composición racional y decoración

exterior de esos estilos. El énfasis decorativo se cuidará a medida que

la obra esté próxima a la ciudad o exija manifestar algún significado

concreto, como solía ocurrir con las piezas que albergan a las Juntas del

Puerto.

Es una arquitectura funcional proyectada para facilitar

las operaciones portuarias con la mayor eficacia y ahorro de tiempo, y eso

se refleja en su composición, estructura y localización en el espacio

del puerto. De este modo esta arquitectura explica el puerto y contribuye

a la construcción de ese imaginario como relato del que hablaba

Bachelard.

Alicante constituía un buen catalogo de esa

arquitectura del puerto moderno decimonónico que se extiende hasta los

pasados cincuenta. Desgraciadamente la mayor parte de ese legado

patrimonial ha sido derribado.

Las recientes operaciones de cambio de uso del puerto

alicantino son el resultado de la hegemonía de una lógica del mercado y

del consumo por encima de otras consideraciones-que ni se han contemplado-

entre las que destacaría dos: En primer lugar la necesaria reflexión del

papel de los espacios portuarios que, liberados de su uso para el trafico

portuario, debían de tener en el conjunto de la ciudad, y en especial de

su fachada marítima; y en segundo lugar una valoración de las

extraordinarias posibilidades paisajistas que se abren al reencuentro de

la ciudad y el mar por intermedio del puerto.

Este cúmulo de torpezas, ausencia de sensibilidad e

intereses privados, como no podía ser de otra manera, se expresa con una

arquitectura desoladora. Desde la escenografía banal de la zona de

Levante al contenedor del Panoramis, metido con calzador en el muelle de

Poniente, estas arquitecturas no recogen-incluso desprecian- el sentido

profundo que siempre ha tenido la relación de la ciudad con el mar y el

puerto. Son arquitecturas rutinarias destinadas a servir de contenedor de

actividades que se sirven del mar y el puerto como reclamo. En esos nuevos

espacios del consumo se deja de ser ciudadano para convertirse en cliente.

Frente a este estado de cosas aparecen dos proyectos de

Javier García-Solera que nos reconcilian con esa fachada urbano-portuaria

tan maltratada. Uno de ellos ya construido, es el Embarcadero, emplazado

como una rótula entre las dos alineaciones del muelle de costa. El

segundo es el proyecto presentado a concurso de remodelación de la

Estación Marítima que, desgraciadamente, no resultó ganador.

Hay una relación entre esta arquitectura y la de los

ingenieros portuarios de formación racional de los que hemos hablado.

Ambas tienen al mar como protagonista, y mientras que la mirada de los

ingenieros es netamente funcional, la de García-Solera es una mirada

poética. Las dos son verdaderas y honestas.

La profesora Carmen Jordá ha escrito un texto muy

hermoso, y al mismo tiempo reflexivo, sobre la obra de este arquitecto. En

él hace un recorrido desde la experiencia interior(en su doble sentido

metafórico y espacial), afirmando que la experiencia de la

arquitectura se realiza y se entiende, ante todo, desde el interior de las

obras, donde aflora el registro sensible del arquitecto con mayor

evidencia. Precisamente la autora encuentra en la idea de patio una de

los invariantes de la arquitectura de este arquitecto alicantino.

Sin embargo el Embarcadero esta concebido como una

ventana abierta al espejo de agua de la dársena. La idea de patio

recogido, con vocación de intimidad, deja paso a la fluidez visual, a la

continuidad que el espacio interior del Embarcadero produce entre el

espacio urbano y el puerto. Sus formas puras y rotundas, que parecen

querer volar sobre la lámina de agua- el único fragmento de ella que

todavía no ha sido ocupada por pantalanes y barcos deportivos-, nos

devuelven la emoción de la mirada original sobre el mar.

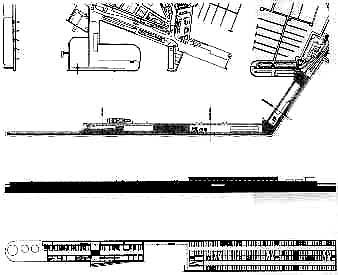

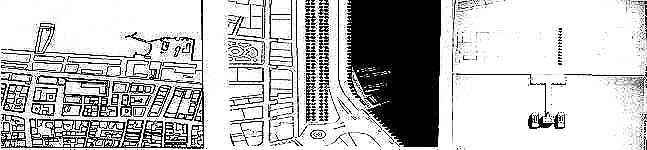

Me ha parecido interesante traer las plantas de alguno

de los proyectos que se realizaron en el puerto Tesalónica en 1997 y con

los que el Embarcadero de Alicante está relacionado en cuanto a programa

y emplazamiento.

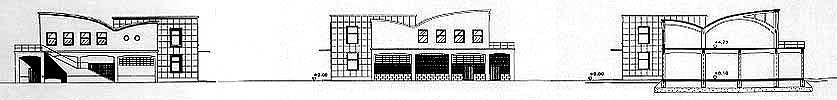

El concurso de proyectos para la remodelación y

ampliación de la Estación Marítima de Alicante se propuso sobre una

obra proyectada en 1959 por el Ingeniero de Caminos Pablo Suárez, autor

del derribado edificio-para poder construir un aparcamiento- de la Junta

del Puerto y Comandancia Marítima en la Plaza del Mar. La arquitectura de

este ingeniero se inscribe en la tradición racionalista de esa profesión

en la que, como decíamos, lo esencial es la función y la construcción,

mientras que los motivos decorativos y tratamiento de fachadas son el

resultado del "gusto" personal del autor. Esta obra junto con la

estación de Autobuses(1944) del arquitecto Félix de Azúa, son las

mejores obras de arquitectura estructural de hormigón en Alicante en los

años 40 y 50 del siglo XX.

La Estación Marítima estaba proyectada para responder

a unas exigencias de transporte naval que giraba en torno a barcos que

hacían la ruta Alicante-Baleares y que tenían apenas unas decenas de

metros de eslora. Ahora, cuarenta años después, ha habido un notable

cambio en esas dimensiones, lo que impone una nueva escala en la

arquitectura para este tipo de instalaciones y servicios portuarios. Este

era uno de los retos más atractivos del concurso: Como resolver el

conflicto de escalas entre una pieza del patrimonio arquitectónico

portuario proyectada para aquella escala y las nuevas exigencias para

barcos que no suelen bajar de 200 metros de eslora.

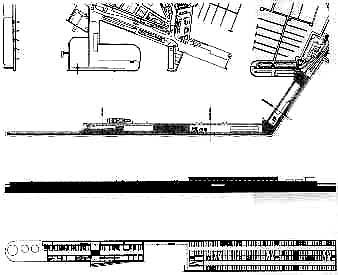

El proyecto de García-Solera se inserta en una

propuesta de remodelación de todo el muelle 14 en donde se encuentra

emplazada la Estación Marítima. Es un enfoque correcto que de haberse

realizado hubiera dado unidad y coherencia a toda ese área, al contrario

de lo que esta ocurriendo ahora con las actuaciones en el puerto de

Alicante, que se producen puntualmente, aisladas, generando un espacio muy

fragmentado. Hay que resaltar también en el proyecto el mantenimiento de

las grúas en su emplazamiento actual.

El proyecto que comentamos mantiene la estructura

original de la Estación. La planta baja del edificio existente, que

mantiene exento, la dedica a servicios y aparcamientos, mientras que en la

superior sitúa el hall de viajeros aprovechando la diafanidad del espacio

que permite la estructura de hormigón armado. Junto a la Estación

Marítima se proyecta una gran pieza para aparcamientos, conectada con

aquella a través de una terraza corrida sobre la dársena, prolongación

de la ya existente.

Como se ve en las secciones transversales, todo el

conjunto se proyecta buscando la mirada sobre el mar, sobre la dársena o

sobre el mar abierto por encima del espaldón del dique, por donde

discurre el paseo más hermoso de la ciudad, pero su uso esta prohibido a

los ciudadanos.

La idea más singular del proyecto, lo que lo define en

el paisaje portuario, es una "piel" de tubos de acero inoxidable

que envuelve a las dos piezas proyectadas, incluso a unos depósitos

situados en el extremo del muelle.

Esta potente solución introduce- además de dar una

unidad al conjunto- una escala intermedia que articula la del muelle y

dique existente con la de los grandes cruceros. La gran pantalla de tubos,

entre los que se dejaría una ligera abertura, al iluminarse desde el

interior generaría un efecto visual como el casco de un gran buque.

Las arquitecturas de García-Solera construidas y

proyectadas en el puerto de Alicante dejan en evidencia a todo lo que se

está haciendo allí. La obra de este arquitecto es el único gozo que se

nos ha permitido en el puerto, porque es una arquitectura que asomándose

al mar nos enseña a mirarlo.

|

In the ports of coastal cities there is a confrontation of scales: that

of the territory; that of the city; that of the place. Each contributes

its own logic to form a single, unique landscape. There is another scale:

that of the sea, as impossible to measure as the invisible paths that

cross it, paths of which nothing is visible but their beginning and their

end: the port.

The territorial scale of the port is present by its very nature as the

node of a terrestrial communications system of roads and railways that

constitutes the field of action of the port’s hinterland. These lines of

transport were laid out in the direction of the port, shaping the

territory and also helping to form the urban space as they penetrated into

the city. As Braudel, the great historian of the Mediterranean, wrote:

Cities and routes, routes and cities, form a single, unique aspect of

the human equipment of space. Whatever its form may be, whatever its

architecture or the civilisation that enlightens it, the Mediterranean

city is always the child of space, creator of routes and, at the same

time, created by them.

The port city cannot be explained without the port, with which it has

had, and has, close social and economic ties. The sea façade of the port

city is incomprehensible without the port that identifies it and gives it

form. This relationship intensifies as the city and port become more

physically interwoven, such as in Barcelona, Alicante, Almería or

Málaga, among other Mediterranean cities.

The port, as place, contributes all its wealth of signification. As the

engineer José A. Fernández Ordóñez said: From time immemorial,

through public works, man has shaped space and appropriated it, signalled

and signified it, creating a place in Heidegger’s sense of the term. The

port is a place of limits and the limits create place and architecture. As

a limit between the land and the sea and as a limit imposed on the sea by

the shapes of the docks and sea walls, the port takes the form of an

architecture where the quays are the building and the basins their

negative where the sea becomes tame.

The port imposes a limit on nature, order on the shore; it is a door

between a known interior and an unknown exterior. Nobody has interpreted

all the symbolic and poetic tension hidden in the limit between the earth

and the sea better than Eduardo Chillida in his Peine del Viento

[or Peine de los Vientos] (Wind Combs) at San Sebastian. As

he himself says:

What was it that defined the place of the Peine del Viento? Firstly, an

essential reflection for anyone who undertakes the task of acting on the

edge of the coast: its dialectic reality. The coast is at the same time

the beginning and end of a territory, of a city... Very elementary things

were happening in this place: the horizon back there, the existence of the

sea and its struggle, men approaching to look at the unknown from the past

to today, when we continue to look without knowing what lies behind.

The spatial and morphological continuity of the city and the port was

sundered in the course of history. The modern Mediterranean port, which

emerged around the middle of the 19th century, began to break away from

the city and set itself up as an autonomous landscape constructed with

functional logic.

The port is not only subject to the changes imposed on it by the

technical innovations involved in its very construction and in marine

transport, but also to the cultural transformations that lead the

imagination of the public. To the eyes of those who look at it, it will

carry the accumulation of all this external and internal experience.

The works to change the use of the old port spaces of Spain, which have

been so frequent since the 1990s, should have gathered together all this

wealth of memory and imagination concerning the sea and incorporated it

into the form and significance of the new port spaces and architectures,

in a dialogue between the timelessness of the sea and the memory of

mankind that brings together works as far apart in time as the Greek

temple of Sunion and Cesar Portela’s cemetery at Finisterre.

I

Gaston Bachelard sustains that imagination is not the ability to form

images of reality, as this constitutes the world of what is perceived. For

him, imagination constructs images of what is invisible. The perceptive

imagination is modified through the influence of cultural changes while

this other imagination, which he calls the creative imagination,

belongs to the interior of the human soul, with roots that go back to the

remote origins of our culture. This French philosopher thereby proposes a

very different interpretation of landscape to that which is founded on

representation. The attraction of the landscape is a love that is based

elsewhere, as he writes in Water and Dreams. Matter such as

water unleashes an imagining that has its source in the basic baggage of

the human mind.

For Bachelard, however, sea water and fresh water call up different

imaginings. The fresh water of a spring or a lake is born and grows, has

shape and memory, while the sea has neither shape nor memory: both are

given to it by the port.

Fresh water is the true water of myth, writes Bachelard, but he

adds that sea water also has its own mythology, although its roots lie

rather in the tale than in the matter itself: The first experience of

the sea belongs to the order of tales, he says in the same book.

However, the sheet of water in the old docks of the Mediterranean ports

built from the mid 19th century onwards reminds us of a lake; its watery

mirror reflects the city, duplicates it. The sheet of water in the 19th

century port is shaped by the structure of two sea walls, one to the east

and the other, the outer one, to the west. This model is very common in

ports such as Tarragona, Alicante, Almería or Málaga.

The great sheet of water spread in front of the city would have been

quite a sensation for the inhabitants, firing their imagination and

emotions. In Alicante, for instance, the great inner basin of the port

built in the last third of the 19th century covers 24 hectares and almost

the entire city built up to that time could have fitted into it.

The dock of the 19th century port became an ever-changing spectacle.

The port is a place where one looks, a scene of ephemeral architectures

along the fixed limits and emphatic edges of the quays. As Alain Corbin

wrote:

A walk along the quays and sea walls, which will perpetuate itself in

new ways, expresses the fascination exerted by a scene where enthusiasm,

activity, heroism and misfortune are displayed in a particularly evident

manner. It is a scene that in all logic fits in with the classic voyage.

Nature has now retreated before the work of man, who has shaped the stone

and remade the limits God assigned to the ocean.

Built on an artificial land of wharves and docks, the Mediterranean

port landscape was completed during the period from the 1890s to the 1920s

by equipping it with architecture and loading and unloading machinery.

Sheds, warehouses and cranes provided the identifying, differentiating

signs of the new landscape. This industrial landscape became increasingly

separated from the city as the nature of the port operations made it

incompatible with the city.

However, the inhabitants of the port city saw a source of present

riches and material well-being in this industrial landscape, in the coming

and going of the sailing ships and steamers and in the smoking steam

machines that ran alongside the first sea front promenades such as the

Explanada in Alicante, designed by the port engineers in about 1916. The

modern port, like an iron bridge or a railway station, is a powerful

prompter of images of progress, which, to the nineteenth century mind, was

a sentiment that linked technical advances with moral improvement and the

hopes of humanity.

The period when the modern port began to be built brought a new vision

of the sea and its shores. It was no longer seen as a marshy place that

engendered miasmas which transmitted illnesses: the therapeutic virtues of

sea water were discovered and sea bathing became widespread.

The port summarises all this new culture of the sea. The modern

Mediterranean port was built on quays that reach out into the sea like

protecting arms, quays sewn onto the city so the port is like a prosthesis

placed on the coastline to solve man’s impotence against nature. As

Gómez de Liaño has said:

All coastal cities are sectioned cities. The sea cuts them off and

presses them to the land at the same time as it launches them and scatters

them on its thousand routes. The port, with its sheds, customs posts and

quays, like the pins of a plug that connects the land to the sea, the

port, I say, is the door – as the pontos is the bridge – that

communicates the visible city with an invisible fantasy city that is

always far, near, the same and different and is built discontinuously in a

series of sudden apparitions.

II

The port architectures of the modern port were designed by civil

engineers who had received architectural training at the School of Civil

Engineers. Their training combined a knowledge of the work of J.N.L.

Durand, whose Précis was a set text for the subject of

Architecture from the mid 19th century, with that of the historicist and

eclectic languages of the end of that century. Consequently their

architecture is rational in composition and the exterior decoration

follows those styles. More attention was paid to decorative emphasis as

the work drew closer to the city or had to display some particular

significance, as was usually the case of the buildings to house the Port

Authority.

It is a functional architecture, designed to facilitate the work of the

port with the greatest efficiency and time saving, and this is reflected

in its composition, structure and position within the port. As a result,

it explains the port and helps to construct that imagining-it-as-a-tale of

which Bachelard spoke.

Alicante constituted a good catalogue of such a modern nineteenth

century port architecture, which continued into the nineteen-fifties.

Unfortunately most of this heritage has been demolished.

The recent operations to change the use of the port of Alicante come

from the hegemony of a logic that puts the market place and consumption

above other considerations (which were not even contemplated). I would

like to mention two such considerations: firstly, the need to reflect on

the rôle that the port spaces, freed from their use for shipping, should

play in the city as a whole, particularly in its seaward façade, and

secondly, an assessment of the extraordinary landscape possibilities that

this opens up for the city and the sea to reencounter each other through

the port.

Such a concatenation of private interests, clumsiness and total lack of

sensitivity is expressed by a desolating architecture. How could it be

otherwise? From the banal scenery of the Levante or eastern quay to the

container of the Panoramis forced into the Poniente or western quay, none

of the architecture reflects (it even despises) the profound meaning that

the city’s relationship with the sea and the port has always had. This

is all routine architecture, designed as containers for activities that

use the sea and the port as a lure. In these new spaces of consumption one

ceases to be a citizen and becomes a client.

Faced with this situation, two projects by Javier García-Solera

reconcile one to this much abused port-urban façade. One has already been

built: the Embarcadero or local ferry terminal, placed like a knee-cap in

the angle of two lines of the shore-line quayside. The second is the

project to remodel the Ferry Terminal, which, unfortunately, did not win

the competition.

There is a relationship between his architecture and that of the port

engineers with their rationalist training. In both cases the emphasis is

on the sea and although the engineers had a distinctly functional view

while García-Solera’s is poetic, both are honest and true.

Professor Carmen Jordá has written a very beautiful and at the same

time thoughtful text on the work of this architect. She starts by looking

at the interior experience (in both senses, metaphorical and spatial) and

affirms that the experience of architecture is realised and understood,

above all, in the interior of his works, where his sensitive register most

obviously surfaces. She finds the idea of the courtyards to be one of

the constants in the architecture of this Alicante architect.

However, the Embarcadero building is conceived as a window that opens

onto the mirror of water in the basin. The idea of a secluded courtyard,

designed to be intimate, gives way to visual fluidity, to the continuity

that the interior of this building sets up between the urban space and the

port. Its pure, categorical forms, which seem to want to fly over the

sheet of water (the only fragment of it that has not yet been occupied by

jetties and leisure craft) give us back the emotion of the original view

over the sea.

I found it interesting to look at the ground plans for some of the

projects carried out in the port of Thessalonica in 1997, to which both

the programme and the siting of the Embarcadero are related.

The competition for projects to remodel and extend Alicante’s Ferry

Terminal concerns a building designed in 1959 by a civil engineer, Pablo

Suárez, who also designed the Port Authority and Marine Authority

building in the Plaza del Mar (since demolished to make way for a car

park). Suárez’s architecture is in the rationalist tradition of his

profession: as mentioned above, what is essential is the function and

construction while the decorative motifs and treatment of the façades are

a result of the designer’s personal tastes. This building and the Bus

Station (1944) by the architect Félix de Azúa are the best works of

concrete structural architecture in Alicante from the 1940s and 1950s.

The Ferry Terminal was designed to meet the needs of the shipping of

the time. This revolved around the boats that plied the Alicante-Balearics

route, with a length that was only measured in multiples of ten. Forty

years later, the length of the shipping has grown considerably and a new

scale is required of the architecture for this type of port installations

and services. How to solve the conflict of scale between a building that

forms part of the port’s architectural heritage, designed on the former

scale, and the new requirements of ships which are seldom less than 200

metres in length was one of the most attractive challenges of the

competition.

García-Solera’s project included a proposal to remodel the whole of

quay 14 where the Ferry Terminal is located. This is a correct approach.

Had it been carried out it would have united and given coherence to the

whole area, unlike what is now happening in the port of Alicante, where

works are being carried out sporadically, in isolation, generating a

highly fragmented space. Another feature of the project that deserves to

be mentioned is that it retained the cranes on their present site.

His project retained the original structure of the Terminal, keeping

the existing building free-standing and placing services and parking in

its ground floor and the waiting room on its upper floor, taking advantage

of the open plan made possible by the reinforced concrete structure. He

designed a large car park building next to the Ferry Terminal, connected

to it by a continuous terrace jutting out over the dock, an extension of

the existing one.

As can be seen in the cross-sections, the complex is designed to look

out to sea, over the dock and over to the open sea beyond the sea wall -

this barrier has the best walk in the city but the public are not allowed

to use it.

The most unusual idea in his project, the one which defines it within

the port landscape, is a "skin" of stainless steel pipes that

surrounds the two buildings and even extends to some tanks at the end of

the quay.

As well as unifying the whole, this powerful solution introduces an

intermediate scale that articulates the scale of the existing quay and sea

wall with that of the big cruisers. When lit from inside, the great screen

of pipes, with a small opening left between them, would create a visual

effect like the hull of a great ship.

García-Solera’s architecture for the port of Alicante, whether built

or designed, shows up everything that is being done there. The work of

this architect is the only pleasure we have been allowed in this port, an

architecture that looks out to sea and teaches us to look at the sea.

|

5

6

7

14

15

16

|

Imágenes

1. Pintura de Emilio Varela (1887-1951)del puerto de

Alicante antes de la Guerra Civil (1936-1939) / Painting by Emilio Varela

(1887-1951) of the port of Alicante before the Spanish Civil War

(1936-1939)

2. Puerto de Alicante. Edificio de la Junta del Puerto

y Comandancia Marítima. Derribado / Port of Alicante. Port Authority and

Marine Authority Building. Demolished.

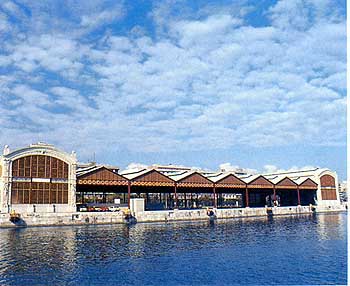

3. Puerto de Castellón. Almacén rehabilitado / Port

of Castellón. Rehabilitated warehouse.

4. Tinglado del Puerto de Alicante construido en torno

a 1916. Derribado en la reciente operación de cambio de uso en el área

de levante / Shed in the port of Alicante built around 1916. Demolished

during the recent operations to change the use of the eastern area of the

port.

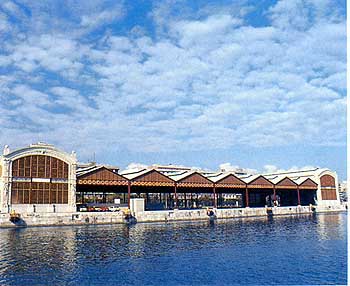

5. Puerto de Valencia. Tinglados. Un ejemplo de respeto

al patrimonio arquitectónico portuario / Port of Valencia. Sheds. A

example of respect for the architectural heritage of the port.

6. Puerto de Alicante. Estado actual de la dársena interior /

Port of Alicante. Current state of the inner dock.

7. Puerto de Alicante. La nueva zona de levante / Port

of Alicante. The new eastern area.

8. Puerto de Tesalónica. Proyecto de Alvaro Siza /

Port of Thessalonica. Proyect by Alvaro Siza.

9. Javier García-Solera. Proyecto de Embarcadero.

Emplazamiento. / Javier García-Solera. Local ferry terminal project. Site.

10. Puerto de Tesalónica. Proyecto de Mario Botta./

Port of Thessalonica. Proyect by Mario Botta.

11. Puerto de Tesalónica. Proyecto de Enrique

Miralles. / Port of Thessalonica. Proyect by Enrique Miralles.

12. Interior actual de la nave superior de la Estación

Marítima. / Present interior of Ferry Terminal upper storey.

13. Estación Marítima. Sección del proyecto

original./ Ferry Terminal. Section of the original project.

14. Puerto de Alicante. En primer término el

Embarcadero de García-Solera. Al fondo el Panoramis y el Club de Regatas.

Se puede observar la radical segregación que se produce entre el Parque

de Canalejas, a la derecha, y el paseo de la dársena. La superficie plana

que se observa entre la carretera y el puerto es la cubierta de un

aparcamiento. / Port of Alicante. In the foreground, García-Solera’s

Embarcadero (local ferry terminal). In the distance, the Panoramis and the

Regatta Club. It will be seen that there is a radical segregation between

Canalejas Park, on the right, and the dock-side walk. The flat surface

between the road and the port is the roof of a car park.

15. Puerto de Alicante. Fachada a la dársena del

Panoramis./ Port of Alicante. Façade at the Panoramis dock.

16. Embarcadero. / Local ferry terminal.

Referencias bibliográficas

Gómez de Liaño, I. Paisajes del placer y de la

culpa. Tecnos. Madrid. 1980.

Braudel,F. El Mediterráneo y el Mundo Mediterráneo

en la época de Felipe II. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Madrid. 1976.

Navarro Vera, J.R. Puerto y Ciudad en la Comunidad

Valenciana. Universidad de Alicante. 1998.

Bazal, J. El Peine del Viento. Ediciones Q.

Pamplona.1986.

Bachelard, G. El Agua y los Sueños. Fondo de

Cultura Económica. 1993.

Corbin, A. El territorio del vacio. Mondadori.

Barcelona. 1988.

Jordá Such, C. Javier García-Solera. Documentos

de Arquitectura. 45. Almería. 2000.

Bibliography cited

Gómez de Liaño, I. Paisajes del placer y de la

culpa. Tecnos. Madrid. 1980.

Braudel, F. El Mediterráneo y el Mundo Mediterráneo

en la época de Felipe II. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Madrid. 1976. [The

Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II,

translation by Sian Reynolds, paperback 1996].

Navarro Vera, J.R. Puerto y Ciudad en la Comunidad

Valenciana. Universidad de Alicante. 1998.

Bazal, J. El Peine del Viento. Ediciones Q. Pamplona. 1986.

Bachelard, G. El Agua y los Sueños. Fondo de

Cultura Económica. 1993. [Water and Dreams and Essay on the Imagination

of Matter, translation by Edith R. Farrell, paperback].

Corbin, A. El territorio del vacio. Mondadori. Barcelona. 1988.

[The Lure of the Sea: the discovery of the seaside in the Western world

1750-1840, hardback 1994, paperback 1995, translation by Jocelyn

Phelps of Le territoire du vide: l’Occident et le désir du rivage

1750-1840].

Jordá Such, C. Javier García-Solera.

Documentos de Arquitectura. 45. Almería. 2000.

|