|

"Con el fin de elevar nuestra cultura a un nivel superior, estamos obligados, nos guste o no, a cambiar nuestra arquitectura. Y esto será posible sólo si liberamos las habitaciones en que vivimos de su carácter de clausura. Esto sin embargo, sólo podremos hacerlo, introduciendo una arquitectura de vidrio que admita la luz del sol, de la luna y de las estrellas, no solamente a través de unas pocas ventanas, sino a través de tantas paredes como sea posible, las cuales se compondrán enteramente de vidrio de

color".1

Paul Scheerbart

Glasarchitektur, 1914

La luz ha desempeñado siempre un papel esencial en la definición de la forma arquitectónica. La silenciosa presencia de la luz ha materializado volúmenes y ha desmaterializado espacios. La inmensa luminosidad mediterránea potenciaba la masividad de la arquitectura clásica mientras la tenue luz nórdica creaba una atmósfera a medio camino entre el cielo y la tierra en el interior de las catedrales góticas. La luz se ha usado, como en el teatro, en la arquitectura barroca para configurar escenarios sobrecogedores donde alcanzar el éxtasis o ser adoctrinado. La luz ha generado sombras sin las cuales sería imposible concebir arquitecturas visionarias como las de Boulleé, y desde luego ha sido uno de los instrumentos fundamentales de la revolución operada por el Movimiento Moderno en la percepción del espacio arquitectónico. Desde Sant' Elia y Mendelsohn hasta Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn o Tadao Ando, la arquitectura del siglo XX ha buscado en la luz el mecanismo para superar el concepto clásico del espacio. La luz cualifica y eleva a la categoría de obra maestra Ronchamp, la Tourette, el Palacio del Capitolio de Dhaka o la capilla del Monte Rokko.

Resulta difícil establecer una relación directa entre el texto de Paul Scheerbart y la Maison de Verre de Pierre Chareau, aunque la luz que tamizan las fachadas de esta casa hacen más reales que nunca aquellas proféticas palabras.

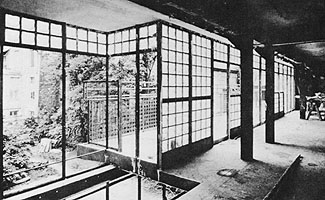

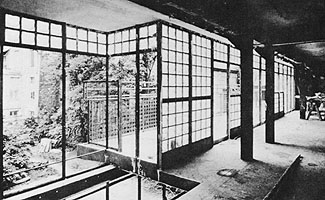

Con anterioridad a la Maison de Verre, otras arquitecturas habían buscado potenciar las cualidades del vidrio; así, tenemos la biblioteca de la Escuela de Arte de Glasgow, célebre obra de Mackintosh, la fachada posterior de la LoosHaus en Viena de Adolf Loos, o el Pabellón de Cristal de Bruno Taut. En todas ellas el cerramiento, incluso por su forma de subdividir la superficie vidriada en pequeños cuadrados, anticipan iconográficamente la fachada de la Maison de Verre, aunque sin la audacia de cubrir por completo la superficie con vidrio. Kenneth Frampton atribuye a la relación de Chareau con discípulos de Hoffman y con Adolf Loos el germen del uso del vidrio en fachada. Especialmente la conexión de Loos con la arquitectura japonesa, en la que se usaba paneles de papel de arroz para subdividir espacios, parece que influyó en obras como el Loos Bar, la casa en la MichaelerPlatz o la casa para Tristan Tzara. Y según el crítico inglés, la estrecha relación de Loos y Gabriel Guevrekian con Chareau en París, en los años 20, supuso una influencia clara en la posterior articulación de materiales y la concepción del interior de la Maison de

Verre.2

Parece que la labor de Bernard Bijvoët, el arquitecto holandés asociado con Chareau para la construcción de esta casa, queda al margen de la obra, algo que ha desmentido con vehemencia Luciano Rubino en un texto posterior al artículo de Frampton. Según el profesor italiano, la figura de Bijvoët es clave para explicar el uso de los bloques de pavés de la Maison de Verre. Bijvoët había trabajado con Duiker en Holanda, a donde regresaría en los años 30, y allí habría entrado en contacto con obras como la iglesia en la Haya de Berlage, o la cooperativa "De Volharding" de J.W.E. Buys, además de otras anónimas que en aquel período se estaban construyendo en Holanda, Alemania o

Checoslovaquia.3

Por tanto, si algo pudo aportar Bijvoet al proyecto fue precisamente su familiaridad con las paredes de vitro-cemento, especialmente si tenemos en cuenta que en el París de aquel momento aún no se había realizado un cerramiento de esas características, con la precisión y perfección de ejecución que presenta la Maison de Verre. Pensemos, por ejemplo, que Le Corbusier no usará hasta un año después, en 1929, un cerramiento similar en la Armeé du Salut, o cuatro más tarde, en 1932, en la Maison Clarté.

Lo que parece claro, sea cual sea el grado de participación de Bijvoët en la concepción de la fachada, es que ésta supone un hito en la historia de la arquitectura, un símbolo cuya faz está tejida como si de un velo se tratara, a veces inquietante, a veces sorprendente, pero siempre sugerente.

A modo de observación interpretativa

A principios del siglo XX Ortega y Gasset escribió un artículo en el que reflexionaba sobre la percepción y la naturaleza de las superficies que de modo inconsciente nos remite a las cualidades de la fachada de la Maison de Verre.

Escribía: "La dimensión de profundidad, sea espacial o de tiempo, sea visual o auditiva, se presenta siempre en una superficie. De suerte que esta superficie posee en rigor dos valores: el uno cuando la tomamos como lo que es materialmente, el otro cuando la vemos en su segunda vida virtual. En el último caso, la superficie, sin dejar de serlo, se dilata en un sentido profundo. Esto es lo que llamamos escorzo.

El escorzo es el órgano de la profundidad visual, en él hallamos un caso límite, donde la simple visión está fundida con un acto puramente

intelectual".4

Este "sentido profundo" que Ortega y Gasset aprecia en las superficies es el mecanismo intelectual con el que los artistas pictóricos representan la profundidad espacial real sobre un lienzo de dos dimensiones. Especialmente a partir del siglo XVII dicha profundidad perseguía dos objetivos: por un lado ofrecer una sensación de espacio tridimensional configurada por planos a distintas profundidades, y por otro plasmar las ideas de movimiento y tiempo, puesto que sólo esa visión de profundidad les permitía representar los actos tal como se desarrollan en la conciencia. No sólo representaban una profundidad espacial, sino también temporal, utilizando para ello los propios planos escorzados; es decir, en el mismo cuadro, aunque en dos espacios diferentes, se daban situaciones consecutivas en el tiempo y sin embargo representadas en el mismo instante. Dos buenos ejemplos de este fenómeno pueden ser Las Hilanderas de Velázquez o Los fusilamientos del tres de mayo de Goya. Posteriormente, los artistas cubistas evolucionarían hacia una técnica de representación en la que se comprime la tridimensionalidad en un espacio tan poco profundo que tendemos a interpretarlo como bidimensional.

Y es en el desarrollo de esta estética del cubismo analítico donde Colin Rowe inicia su estudio sobre la transparencia en pintura y posteriormente en arquitectura, distinguiendo lo que él llama transparencia literal y fenomenal. La transparencia literal será aquella resultado de las características propias de los materiales, mientras la fenomenal será aquella inherente a la organización de los planos de profundidad. Es decir, mientras la transparencia literal depende de las cualidades físicas de los materiales que forman las superficies de las fachadas (y aquí tenemos un amplio abanico de posibilidades en la gradación que va de lo transparente a lo opaco), la transparencia fenomenal alude a una acción intelectual derivada de la composición de dichas superficies de fachada en planos a distintas profundidades que pueden leerse de forma más o menos

ambigua.5 De esta forma el crítico inglés aplica al arte la definición de transparencia introducida por Gyorgy Kepes según la cual "lo transparente deja de ser lo que es perfectamente claro para convertirse en lo claramente ambiguo".

Si alguna cualidad tiene la fachada de la Maison de Verre en París, es la de presentarnos una visión del interior sustancialmente ambigua. Como telón de fondo del escenario configurado por el patio de entrada nos ofrece una visión sesgada de la vida detrás de bambalinas. La representación de la vida pública y privada de sus inquilinos debemos reconstruirla a partir de la información que nos revelan las sombras del interior, con lo que de ejercicio de la imaginación esto supone. Los propietarios de la casa la eligieron por su privilegiada ubicación, próxima al barrio de Saint Germain, el centro de la vida social e intelectual del París de finales de los años 20. Dejando para más tarde consideraciones técnicas sobre la fachada, podemos imaginar el júbilo de los inquilinos al pensar que las fiestas de sociedad que iban a celebrar no sólo serían de ámbito público en el interior, sino también en el exterior a través de la piel de vidrio que los ocultaba, lo justo, de miradas ajenas. Una piel de vidrio que, continuando con analogías teatrales, hacía las veces de biombo, mostrando sólo aquello que interesa y dejando a la imaginación que componga la imagen completa de lo que hay detrás. La fachada de la Maison de Verre, como biombo, posee un doble valor: el suyo propio derivado de la calidad de su superficie, textura y urdimbre, y el de constituirse en una membrana que con la luz y el movimiento que deja entrever nos dibuja la vida que se desarrolla en su interior. Y es que el biombo, como dice Joaquín Arnau, tenía su

erótica.6

El tratamiento tan extendido de piel que se le da hoy día a la fachada del edificio fue enunciado por vez primera por el crítico alemán Gottfried Semper a mediados del siglo XIX. De los cuatro elementos que según su teoría constituían la arquitectura, y como alternativa anticlásica a la tríada vitruviana utilitas, firmitas, venustas, el recinto era el más importante en tanto que lo presumía el origen de la

arquitectura.7 Los otros tres, el hogar, el basamento y el techo tenían una importancia secundaria. A partir de sus cuatro materiales fundamentales, el tejido, el barro, la piedra y la madera, surgen cuatro técnicas elementales, la textil, la cerámica, la albañilería y la carpintería, que conducen a los cuatro elementos fundamentales antes enunciados. Basándose en los datos que conocía sobre arquitecturas primitivas indígenas llegó a la conclusión del origen textil de la arquitectura y desafió la teoría de la cabaña de Laugier, máxima autoridad en la materia, en la que se daba prioridad al basamento y a la masa portante. Y es que bien pensado, si nuestra primera protección es el vestido, y el vestido no es sino una segunda piel, no es descabellado pensar en una evolución natural hacia la creación de espacios habitables a partir de los tejidos. Por tanto, las tiendas o las chozas pueden considerarse unos segundos ropajes. Así al menos lo entendieron los nómadas al improvisar sus moradas en el desierto, sentimiento nunca olvidado por aquellos otros musulmanes que las petrificaron en arquitecturas de filtros, tamices y veladuras de arcilla, como ocurre en la Alhambra de Granada. Lo cual nos lleva a reflexionar sobre el parentesco etimológico entre el hábitat humano o habitación y el hábito como prenda de

ropa.8

Lo textil, que tan radicalmente había puesto en práctica Adolf Loos en la decoración interior de su propia casa, y tan magistralmente había interpretado F. Ll. Wright en los cerramientos de la casa Alice Millard o la casa Storer, subyace en la concepción contemporánea del cerramiento a través de los esquemas de composición por retículas jerarquizadas, nudos y material de relleno, neutro, abstracto o figurativo. Es el caso de arquitecturas como las de Herzog y de Meuron, Kazuyo Sejima, Toyo Ito o Renzo Piano. Y como precedente ilustre, La Maison de Verre.

Semper distingue entre la masividad del muro (die Mauer) y el cerramiento ligero que designaba con la palabra die Wand. Ambos términos implican envoltura, pero éste último deriva de la palabra Gewand, que en alemán significa vestido y se relaciona con Winden, bordar. Esta sutil diferenciación entre los dos tipos de cerramiento constituye un punto central de la reflexión llevada a cabo por diversos teóricos del siglo XIX sobre la naturaleza de la relación entre revestimiento y construcción o estructura

portante.9 Revelar o enmascarar son los dos extremos en los que se mueve el principio del revestimiento. "Bekleidung" o "Verkleidung", verdad o falsedad en la construcción son conceptos hasta entonces nunca planteados que surgen como consecuencia del desarrollo de nuevos materiales y la aplicación de nuevas técnicas que evidencian la diferente naturaleza y función del cerramiento y la estructura. La solución tradicional en la que el revestimiento es tan sólo una operación de embellecimiento superficial del soporte no se sostiene por más tiempo y constituye el germen de formulaciones teóricas vanguardistas como los Cinco puntos para una arquitectura nueva de Le Corbusier.

Precisamente tres de estos puntos, los que se refieren a la planta libre, fachada libre y ventanas longitudinales se muestran claramente en la Maison de Verre. De hecho, la influencia mutua entre Le Corbusier y Chareau se produce a través de esta casa en forma consecutiva: Chareau materializa la teoría enunciada por Le Corbusier, que siguió de cerca su construcción. Y posteriormente el mismo Le Corbusier usaría en sus propias obras materiales y soluciones extraídas directamente de la Maison de Verre.

La historia de un encargo

Alrededor de 1927, un matrimonio con dinero y buena posición social, los Dalsace, buscaban en París una casa donde fijar su residencia. Debía estar en las proximidades del barrio de Saint Germain que, como dijimos, era el lugar de concentración de la alta sociedad parisina de la época. Cuando dan con el edificio, una casona entre medianeras de varias plantas encerrada en un patio de manzana, el 31 de la rue Saint Guillaume, ésta se encuentra en tan mal estado que tanto los futuros propietarios como el arquitecto acuerdan derribarlo y reconstruirlo. Pero una anciana que vivía en el tercer piso se niega a abandonar su residencia, por lo que finalmente se decide demoler los dos pisos inferiores y mantener lo que había por encima. Esto supuso, a parte de un contratiempo inesperado, la consecución de una proeza técnica al dar solución simultáneamente a dos problemas: por un lado construir el nuevo edificio bajo lo que quedaba sin provocar daños estructurales a las plantas superiores, y por otro iluminar el interior de la nueva vivienda, que por su estrechez y ubicación en el patio de manzana adolecía de falta de luz natural.

Estas dos exigencias determinaron el uso de estructura metálica y la elección del vidrio para la fachada. Por su novedad de uso en el campo de la vivienda (y aquí habría que enfatizar el papel jugado por Bernard Bijvoët) estas dos elecciones dieron a la casa su nombre, todavía vigente en la actualidad.

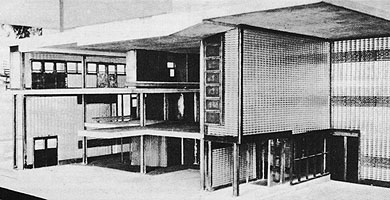

El nuevo proyecto tenía que insertar bajo la construcción que se mantenía un nuevo volumen de tres alturas en el lugar que ocupaban el primer y segundo piso originales, cada uno de los cuales se destinaría a un aspecto específico del estilo de vida de los Dalsace: la primera planta, de acceso, para la actividad profesional, con el gabinete médico a doble altura y las circulaciones y sala de espera alrededor de la secretaría acristalada. Había una entrada común para pacientes e inquilinos, pero ya en el interior la escalera principal, semioculta por paneles abatibles, conducía al segundo

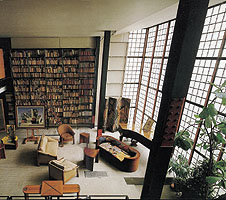

piso.10 La segunda planta albergaba las funciones públicas de la vida de los Dalsace. En ella se encontraba el salón principal, un gran volumen a doble altura con suficiente dimensión como para celebrar pequeños conciertos domésticos. En la parte posterior, más privatizada y tranquila, se proyectaba un pequeño invernadero y un salón de menor tamaño, todo ello volcando al jardín trasero. La tercera planta se destinaba a los dormitorios, todos dando a una terraza en la parte trasera. El acceso, tanto a los dormitorios como a los servicios se realizaba a través de una galería volcada sobre la doble altura del salón principal cuyas barandillas estaban diseñadas para hacer las funciones de librería. Finalmente un volumen lateral en el patio de entrada resolvía la zona de servicios, con la cocina y dependencias para los empleados.

En general se trataba de una estratificación por usos poco novedosa, correspondiente a una típica casa-taller donde se desarrollaban simultáneamente el trabajo y la vida familiar. La novedad reside sin embargo en la macla espacial que se produce entre los distintos niveles, la fluidez en el tratamiento de los espacios interiores y la libertad de distribución interior, todo ello posible gracias a la estructura de acero. También el tratamiento de fachada supone una novedad por cuanto parecen reflejarse en su superficie los ideales de la vanguardia arquitectónica del momento: nuevos materiales, diseño moderno, elementos estandarizados y un proceso constructivo industrializado cuyo fin inmediato era la rapidez de ejecución y el abaratamiento de costes. Sin embargo la realidad fue muy distinta ya que si bien los materiales y las técnicas se hallaban impregnadas de un potencial industrial, una casa prototipo como ésta, sin un sistema madurado de construcción y sometida a la inseguridad técnica de no contar con la garantía de los novedosos productos utilizados, desarrolló unos métodos de construcción muy alejados de lo industrial. El propio Chareau lo confirmaba con el siguiente comentario: "[...] la casa es un modelo hecho por artesanos con pretensiones de estandarización".

Esta circunstancia provocó unos costes desorbitados tanto económicos como en plazos de ejecución: unos 500.000 euros actuales y 4 años para su finalización.

Técnica y materia

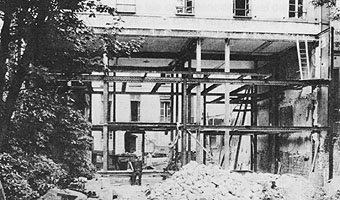

Las fotografías del proceso de construcción nos han permitido conocer las diferentes fases de apuntalamiento durante la ejecución: en una primera fase se demolió el interior y se apeó el piso conservado con la nueva estructura metálica. En una segunda fase se demolieron las fachadas del primer y segundo pisos, por lo que el armazón metálico pasó a soportar la totalidad del peso de la planta conservada. Es notable la dicotomía que se observa entre el diseño tradicional del entramado, rozando un diseño

modernista,11 formado por pies derechos y jácenas unidos mediante cartelas metálicas atornilladas o roblonadas in situ, con la moderna concepción del espacio fluido donde se disocia claramente la estructura sustentante de la distribución interior, dejando los pilares exentos y posibilitando la creación de particiones móviles abatibles o correderas. En efecto, la mayor parte de los tabiques, especialmente en la planta de dormitorios, son practicables; las puertas, que van de suelo a techo, transforman sensiblemente la aprehensión del espacio según estén abiertas o cerradas y confieren una gran versatilidad al interior gracias a su alto grado de mecanización. De hecho, tan sólo la casa Schröeder goza por aquellas fechas de una capacidad de transformabilidad similar, aunque en su caso la transformación del espacio es total, mientras en la Maison de Verre se establecen habitualmente sutiles variaciones que influyen sobre la luz o la visión del espacio. No obstante en el piso de dormitorios sí hay puertas sin marcos y paredes deslizantes que consiguen transformar completamente el espacio. Incluso las instalaciones están diseñadas bajo ese criterio. Se separaba por un lado la conducción de calefacción por aire en planos horizontales bajo los forjados, y por otro, como dos sistemas autónomos, aparecían los tubos verticales que alojaban el cableado de luz, energía eléctrica y telefonía. Estos conductos iban de suelo a techo sin apoyarse en paredes y tenían consolas de control donde se ubicaban las tomas de corriente y los interruptores. De esta forma se liberaba a la albañilería de la función de soporte de instalaciones y se posibilitaba la realización de cambios en la distribución sin afectarla. En todo lo cual tuvo mucho que ver la pericia profesional de Louis Dalbert, un herrero que ya había colaborado en 1918 con Chareau en la decoración de un apartamento para los Dalsace, el mismo matrimonio que años más tarde les encargaría la construcción de la Maison de Verre.

Este modo de concebir la arquitectura potenciado por el uso de artilugios mecánicos como el montacargas, el ascensor privado, la escalera abatible que comunicaba el saloncito privado con el dormitorio principal, etc., dio lugar a una estética maquinista que le sugiere a Kenneth Frampton la idea de que una poética de la técnica invade toda la

casa.12 Y es que el aspecto interior de la casa, los acabados de suelos y paredes, la solución de los detalles constructivos y la desnudez de encuentros, la relación de las instalaciones con las particiones... refuerzan la sensación de estar en una máquina para habitar y materializan las teorías arquitectónicas sobre la verdad del revestimiento y la construcción formuladas por Semper o Bötticher, y las aspiraciones maquinistas de Le Corbusier. De hecho, el maestro suizo visitaba las obras de la Maison de Verre, por la cual sentía una profunda admiración, y es indiscutible la influencia que ésta ejerció en obras posteriores suyas como la Casa de fin de semana en París, la Maison Clarté o el Porte Molitor, donde aparecen fachadas de pavés, iluminaciones indirectas o superficies transformables. Chareau resuelve un problema que adquiere tintes morales decidiendo mostrar las posibilidades de los nuevos materiales (acero, vidrio) y poniendo radicalmente en cuestión la esencia misma de la tradición clásica. Mediante la aceptación de los nuevos materiales ligeros y transparentes con la intención de explotar sus cualidades expresivas, y la superación de la tradición constructiva en la que se identificaba muro portante con cerramiento como un todo indisociable, Pierre Chareau disecciona la estructura portante del revestimiento y rompe por dos veces la tradición vitruviana impuesta por las Academias a la luz de la Ilustración.

Pero toda máquina está compuesta por piezas, y en el caso de la Maison de Verre dichas piezas son los bloques de pavés de las fachadas. Los bloques de pavés se agrupan en unidades constructivas, los paneles, que determinan la escala intermedia entre el detalle y la estructura del proyecto, y nos permiten entender la lógica que hay detrás de la construcción de la casa, así como el proceso de fabricación que justifica muchas de las soluciones desarrolladas por Chareau. Y nos recuerda que el campo de la construcción en sí mismo, lejos de ser un simple problema, permanece como una específica fuente de invención y expresión arquitectónicas.

El mismo Chareau nos da la mejor explicación del origen de la solución que adoptó para las fachadas: "Tenía que construir entre dos paredes medianeras, y en los planos se preveía una división del espacio de acuerdo con necesidades y gustos de los hábitos de vida modernos. Había sólo un camino para conseguir el máximo de luz: construir fachadas completamente traslúcidas. Empecé experimentando en 1927, usando grandes y gruesas planchas de vidrio deslustrados por una cara. Este primer intento no me satisfizo en absoluto. De todos modos, y dando por hecho que los problemas de ventilación y calefacción habían sido solventados de manera muy especial, se adoptó el principio de supresión de las ventanas: habría solamente pequeñas aberturas, por seguridad. En este estado, abandonando la idea de usar grandes bloques de vidrio, empezamos buscando elementos que, una vez ensamblados, pudieran formar superficies ilimitadas, pero sin crear los huecos vacíos de las grandes piezas de vidrio. Estaba fuera de lugar pensar en nuevos materiales para un experimento tan modesto. De entre aquellos que existían, elegí lentes de vidrio tipo-Nevada ya que parecían ser las que mejor se adaptaban a las condiciones del

problema".13

El pragmatismo y la aparente facilidad con la que Chareau habla sobre la manera en que el problema de la iluminación se planteó y posteriormente solucionó no debería enmascarar las dificultades que encontró para llevar a cabo la solución. Tanto es así, que si entre el Pabellón de Vidrio de Bruno Taut para la exposición del Werkbund y la Maison de Verre no hay ningún otro edificio donde el cerramiento sea completamente de vidrio es por falta de desarrollo tecnológico. El uso de vidrio estructural en Francia data de finales del siglo XIX aunque su uso se restringía a pequeñas piezas colocadas en una retícula horizontal de hormigón armado. Posteriormente se desarrollaría en Alemania la tecnología que permitía colocarlos en vertical, pero fue en 1928 la empresa francesa Saint Gobain la que comienza a comercializar, sin ninguna garantía de fabricación, piezas cuadradas de 20x20x4 cm con juntas acanaladas que proporcionaban un excelente acabado exterior. Ahora bien, la empresa se negó a garantizar que sus piezas serían autoportantes, por lo que, para evitar la posible rotura de las piezas situadas en la base, Chareau se vio obligado a crear una cuadrícula de acero que, oculta, agrupaba las piezas en paneles de 4x6 elementos. Este panel se convirtió en el elemento básico del proyecto. A diferencia del bloque de pavés, un producto primario con una sola función y cuyas características dimensionales son establecidas por exigencias técnicas y materiales, el panel, como elemento estandarizado de construcción, es una adición de componentes cuyas dimensiones se establecen más por criterios ergonómicos que constructivos. De este modo, la medida de cuatro bloques de ancho, o 91 cm, permite la creación de una fachada en la cual hay puertas y ventanas con diferentes formas de apertura, así como un gran número de particiones interiores, paneles ocultos, puertas interiores translúcidas u opacas, altas o bajas, fijas o móviles, que cierran por yuxtaposición la práctica totalidad de los espacios interiores y otorgan una excepcional unidad al interior y al exterior.

En el proyecto original se concibieron idénticos armazones para las dos fachadas. Los montantes verticales estaban constituidos por dos perfiles en U de 30x15 mm soldados a una chapa plana de acero de 100x9 mm destinada a rigidizar la fachada. En horizontal, otras dos secciones en U idénticas a las primeras completan la retícula que da soporte a los paneles de pavés. En 1930 Chareau cubrió este armazón de acero con un mortero para materializar una superficie sin juntas aparentes, sin esqueleto visible, como si de un plano transparente ilimitado se tratara. Sin embargo en los años 60 se practicó una intervención que afectó a la fachada principal, donde se eliminó este revestimiento continuo para colocar piezas metálicas que potenciaban la subestructura interior trasladándola al exterior. En la fachada trasera se mantiene la imagen original, y se pueden apreciar los dos sistemas de cerramiento que se emplearon para ella. En la planta baja y la segunda se usaron las mismas piezas de pavés que en la fachada anterior, pero en el primer piso, en la zona del saloncito y el invernadero, se usó un segundo tipo de panel quizá más cercano a un concepto de "muro cortina". El material de relleno era vidrio transparente montado en seco sobre un chasis de acero que dejaba pasar la luz y el sol directamente al interior. Las piezas se atornillaban entre sí dejando una junta de cuero entre ellas para asegurar la estanqueidad y los paneles estaban constituidos por un marco de acero dentro del cual se podía encastrar bien una pieza fija de vidrio, bien una unidad practicable que se deslizaba mediante un mecanismo oculto.

Poética y función

La gran aportación de la Maison de Verre a la historia de la arquitectura se articula en tres aspectos: estandarización, transformación y transparencia.

Mediante la estandarización, la casa remite a un orden modular con pretensiones de producción a gran escala. En virtud de esa industrialización de componentes las piezas no sólo generan multitud de elementos derivados de la sustitución de variables, sino que además son intercambiables; es decir, su potencial para la modificación es también un potencial para su sustitución. De forma que dicha capacidad permite transformar el espacio interior de la casa en base a operaciones que van desde la pura necesidad a la sutil variación poética. Ejemplo de estos dos grados de transformabilidad se dan en el mismo elemento: la escalera principal que sube desde la planta baja al primer piso está en una zona pública de paso que transitan por igual los pacientes que van a la consulta y los propios inquilinos. El rellano de esta escalera está cerrado por una puerta giratoria que separa la zona de la vida privada de la consulta médica, dando solución a una necesidad funcional. Sin embargo, el volumen completo de la caja de la escalera está envuelto por pantallas de chapa metálica perforada que transforman de transparente a translúcido el grado de percepción de la misma, provocando sutiles cambios de luz y respondiendo más a una voluntad de expresión lírica que a una necesidad estrictamente funcional.

Ahora bien, sin lugar a dudas, nadie mejor que el propietario para transmitirnos la sensación de vivir en una caja de cristal como la Maison de Verre: "Gracias a una anciana que no deseaba abandonar su sórdido apartamento en el tercer piso, Pierre Chareau realizó una hazaña estructural consistente en tres pisos luminosos, dentro del piso bajo y el primer piso de esta pequeña casa urbana. Estos dos pisos habían sido tan oscuros, que los empleados de la vieja señora, que viviría hasta los cien años, estaban obligados a trabajar a lo largo de todo el día con luz artificial. La luz penetra libremente, alrededor del cual la planta baja está dedicada a la consulta, el primer piso a la vida social y el segundo a morada nocturna. El problema que se planteó era enormemente difícil de resolver. La interpenetración de habitaciones, algunas de las cuales atravesaban dos pisos (por ejemplo la sala de consultas y el vestíbulo) hizo que el problema del aislamiento del ruido fuera muy difícil... El piso bajo, la parte profesional de la casa, facilita el trabajo y permite a los clientes, una vez que ha desaparecido su ansiedad, una gran sensación de calma. La casa en su conjunto fue creada bajo el signo de la amistad, en perfecta armonía

afectiva".14

Esta convergencia de intereses entre cliente y arquitecto fue lo que hizo posible la construcción de la Maison de Verre. Y es significativo que esta "conexión", especialmente cuando el cliente era médico, haya dado lugar a la construcción de algunas de las obras de arquitectura doméstica más paradigmáticas de la vanguardia de la primera mitad del siglo XX: por citar sólo algunas tenemos la villa Karma de Adolf Loos, la casa del doctor Curruchet de Le Corbusier, la casa Lovell de Richard Neutra, la casa Farnsworth de Mies o la que nos ocupa, la Maison de Verre de Pierre Chareau, promovida por un ginecólogo. Parece que el nivel cultural es un factor determinante para que se produzca la mutua comprensión entre el cliente y el arquitecto encaminada a la consecución de aspiraciones espirituales, más allá de la simple construcción de un recinto para vivir.

El Arte, en general, utiliza un soporte para transmitir una idea. El soporte puede ser múltiple; las ideas expresadas, casi ilimitadas. La Arquitectura, sin embargo, debe acordar las ideas con la utilidad; poética y función no son siempre compatibles porque la brecha abierta entre idea y realidad es complicada de salvar. John Hejduk decía que el arquitecto importante es aquel que cuando ha acabado su trabajo, está tan próximo a la abstracción original como le ha sido posible. Frente a una arquitectura teórica que no da el salto desde el papel a la materialidad, Chareau logró construir una obra de arte en la que la idea consiguió sobreponerse a las dificultades técnicas sin renunciar al grado de abstracción que perseguía la vanguardia artística del momento.

|

"In order to raise our culture to a higher level we are forced, whether we like it of not, to change our architecture. And this will only be possible if we free the rooms in which we live from their enclosed character. This, however, we can only do by introducing a glass architecture which admits the light of the sun, of the moon and of the stars, not only through a few windows, but through as many walls as feasible, these to consist entirely of glass - of coloured

glass."1

Paul Scheerbart

Glasarchitektur, 1914

Light has always played an essential rôle in the definition of architectural form. The silent presence of the light materialises volumes and dematerialises spaces. The immense brightness of the Mediterranean favoured the massiveness of classical architecture while the thin light of the north created an atmosphere half way between heaven and earth in the gothic cathedrals. Baroque architecture used light theatrically, creating emotionally charged settings for indoctrination or ecstasy. Light generated the shadows without which visionary works such as those of Boullée could never have been conceived and light was undoubtedly one of the basic instruments of the revolution in the perception of architectural space brought about by the Modern Movement. From Sant'Elia and Mendelsohn to Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn or Tadao Ando, 20th century architecture has looked to light for the means to surpass the classic concept of space. Light gives Ronchamp, la Tourette, the Dhaka National Assembly complex or the chapel on Mount Rokko their special qualities and raises them to the category of masterpieces.

It is difficult to establish a direct link between Paul Scheerbart's text and Pierre Chareau's Maison de Verre, but his prophetic words are more real than ever in the light that is diffused by the façades of this house.

Before the Maison de Verre, other works had sought to emphasise the qualities of glass: Mackintosh's famous Glasgow School of Art library, the rear façade of the LoosHaus in Vienna by Adolf Loos or Bruno Taut's Glass Pavilion. All have exteriors that iconographically anticipate the Maison de Verre, even in the way the glazed surfaces are sub-divided into small squares, although without the audacity of covering the entire surface with glass. Kenneth Frampton attributes the germ of Chareau's use of glass in façades to the influence of Adolf Loos and pupils of Hoffman. Loos' acquaintance with Japanese architecture, which uses rice-paper partitions to subdivide spaces, appears to have been a particular influence in works such as the Kärtner Bar (American Bar), the Michaelerplatz building or the house for Tristan Tzara. According to Frampton, Chareau's friendship with Loos and Gabriel Guevrekian in Paris during the '20s clearly influenced his subsequent use of materials and his concept of the interior of the Maison de

Verre.2

The input of Bernard Bijvoët, the Dutch architect who was Chareau's partner in the construction of this house, would appear to be marginal. This been disputed with some vehemence by Luciano Rubino in a book that postdates Frampton's article. Rubino claims that Bijvoët is a key figure in explaining the use of glass blocks at the Maison de Verre. He had worked with Duiker in the Netherlands (where he was to return in the '30s) and had been in contact with works such as Berlage's church at the Hague or J.W.E. Buys' De Volharding coop department store, as well as other anonymous buildings that were being built at the time in the Netherlands, Germany and

Czechoslovakia.3

Consequently, if Bijvoët had any contribution to make to the project it was precisely his familiarity with concrete-and-glass walls, particularly bearing in mind that in Paris, at that time, no wall of this type had yet been built with the precision and perfect workmanship we find at the Maison de Verre. For instance, Le Corbusier was not to use a similar wall until a year later, 1929, at the Salvation Army hostel, or four years later, 1932, at the Maison Clarté.

What appears to be clear, whatever Bijvoët's contribution to conceiving it may have been, is that this façade is a landmark in the history of architecture, a symbol with a face woven as though it were a veil, sometimes disquieting, sometimes surprising, but always evocative.

.

By way of interpretative observation

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Spanish essayist and philosopher Ortega y Gasset wrote an article in which he reflected on the nature and perception of surfaces, which unwittingly refers to the qualities of the Maison de Verre façade.

He wrote: "The depth dimension, whether spatial or of time, visual or auditory, always appears in a surface. So the surface, strictly speaking, possesses two values: one when we take it as what it is materially, the other when we see it in its second, virtual life. In the latter case, without ceasing to be a surface, it expands in a deep sense. This is what is known as foreshortening. Foreshortening is the organ of visual depth; in it we find an extreme case where simple vision is fused with a purely intellectual

act".4

The "deep sense" that Ortega y Gasset saw in surfaces is the intellectual device that painters use to represent real, deep space on a two-dimensional canvas. Particularly from the 17th century onwards, this depth was used for two purposes: on the one hand, to give a sense of a three-dimensional space, made up of planes at different depths, and on the other, to capture the notions of movement and time, as only this in-depth view made it possible for them to represent acts in the way they take place in one's consciousness. They not only represented spatial depth but also depth of time, using the same foreshortened planes. In other words, the same painting shows situations that are consecutive in time but are nonetheless represented at the same moment, although in two different spaces. Two good examples of this are Velazquez's The Tapestry-Weavers and Goya's Executions of the 3rd of May 1808. Later, the cubists evolved a method of representation that compressed three-dimensionality into such a shallow space that we tend to interpret it as two-dimensional.

The development of the aesthetics of analytic cubism is where Colin Rowe begins his study of transparency in painting and then in architecture, distinguishing what he calls literal and phenomenal transparency. Literal transparency is that which results from the inherent properties of the materials, while phenomenal transparency is that which is inherent in the organisation of the planes of depth. In other words, while literal transparency depends on the physical qualities of the materials that make up the surface of a façade (and here we have a wide range of possible gradations between transparent and opaque), phenomenal transparency refers to an intellectual act that stems from the surfaces of the façade being composed of planes at different depths that can be read more or less

ambiguously.5 This is an architectural application of Gyorgy Kepes' definition of transparency, which Rowe summarises as "the transparent ceases to be that which is perfectly clear and becomes, instead, that which is clearly ambiguous".

If there is one quality that the Maison de Verre façade possesses, it is that of presenting a substantially ambiguous view of the interior. As a backdrop to the stage formed by the courtyard, it offers an oblique view of life in the wings. The playing out of the public and private life of the inhabitants must be reconstructed from the information revealed by the shadows inside, in a leap of the imagination. The owners of the house chose it for its excellent position near the Saint Germain quarter, the hub of social and intellectual life in the Paris of the '20s. Leaving a technical consideration of the façade for later, we can imagine their jubilation at the thought that their society parties would not only have a public dimension in the interior but also on the exterior, through the skin of glass that only just concealed them from alien eyes. To continue with the theatrical analogy, the glass skin acts as a screen, showing only what one wishes and leaving the imagination to complete an image of what is behind it. As a screen, the Maison de Verre façade has two meanings: its own, that which derives from the quality of its surface, texture and weave, and that of constituting a membrane which, by allowing glimpses of light and movement, provides a sketch of the life taking place within. As Joaquín Arnau said, screens have a certain erotic

quality.6

The now widespread concept of the façade as a skin was first expressed by the German critic Gottfried Semper in the mid 19th century. In his theory, of the four elements that constitute architecture (an anti-classical alternative to Vitruvius' triad of utilitas, firmitas, venustas) the enclosure was the most important as he took it to be the origin of

architecture.7 The other three, the hearth, the mound and the roof, were of secondary importance. The four fundamental materials, textile, clay, stone and wood, gave rise to four basic techniques, weaving, pottery, masonry and carpentry, which lead to the four elements of architecture. From the known data about primitive indigenous architectures, he drew the conclusion that the origin of architecture was textile, challenging the cabin theory of Laugier, the maximum authority on the subject, which gave pride of place to the base and the load-bearing masonry. The fact is that if we think about it, if our first protection is clothing and if clothing is merely a second skin, it is not too far-fetched to think in terms of a natural evolution towards creating habitable spaces from textiles. Tents or huts can therefore be considered as a second clothing. This, at least, was how the nomads saw them as they improvised their desert abodes, and the Muslims who petrified them in architectures of filters, sieves and veils of clay, as in the Alhambra in Granada, never lost that feeling. This brings us to a reflection on the etymological relationship between the human habitat or habitation and the habit as a

garment.8

Textiles, so radically employed by Adolf Loos in the interior decoration of his own home and so brilliantly interpreted by Frank Lloyd Wright in the walls of the Alice Millard house or the Storer house, underlie the contemporary concept of the envelope in its compositional schemes of hierarchical grids, nodes and infill materials, neutral, abstract or figurative. This applies to works such as those of Herzog and de Meuron, Kazuyo Sejima, Toyo Ito or Renzo Piano. And to an illustrious precursor, the Maison de Verre.

Semper made a distinction between the massive wall, die Mauer, and the light wall, partition or screen he called die Wand. Both terms imply enclosure, but the latter derives from 'Gewand', which in German means a gown and is related to 'winden', to make by interweaving. The subtle distinction between the two types of wall is a central feature of the reflections of various 19th century theorists on the nature of the relationship between covering and construction or bearing

structure.9 The principle of covering moves between two extremes, revealing and masking. "Bekleidung" or "Verkleidung", clothing or disguise, truth or falsehood in construction, are concepts that had never before been mooted. They arose as a result of the development of new materials and the application of new techniques that made the different nature and function of structure and envelope patent. The traditional solution where the covering is only a superficial embellishment of the support was no longer valid and the seeds of vanguard theoretical formulations such as Le Corbusier's Five Points of a New Architecture were sown.

Three of these five points - free plan, free façade and long windows - are plain to see in the Maison de Verre. Indeed, Le Corbusier and Chareau influenced each other mutually and consecutively through this house: Chareau materialised Le Corbusier's theory and Le Corbusier followed its construction closely and later used materials and solutions taken directly from the Maison de Verre in his own works.

The history of a commission

Around 1927, a married couple with money and a good social position, Dr. and Mrs. Dalsace, were looking for a home in Paris. It had to be in the neighbourhood of the Saint Germain quarter which, as mentioned, was where Parisian high society of the time congregated. When they found the building at 31 rue Saint Guillaume, a big house on several stories between party walls in the central courtyard of the block, it was in such poor condition that both the future owners and the architect decided to demolish and rebuild it. However, an old lady who lived on the third floor refused to move, so they finally decided to demolish the two lower floors and keep what was above them. As well as being an unexpected setback, this meant that a technical feat was required to solve two simultaneous problems: on the one hand, constructing a new building underneath what remained without causing structural damage to the upper floors and on the other, bringing light to the interior of the new home, which suffered from a lack of natural light because of its narrowness and its position in the centre of the block.

These two demands determined the use of a metal structure and the choice of glass for the façade. Because of the novelty of its use in housing (here the rôle played by Bernard Bijvoët must be emphasised), these two choices gave the house the name by which it is still known.

Beneath the part of the building that was to be kept, the new design had to insert a new three-storey volume into the space of the original first and second storeys. Each of the new storeys was designed for a particular aspect of the Dalsaces' life style: the first, on the ground floor, was for the doctor's professional use, with a double height consulting room and a waiting room and circulation areas set around the glazed secretary's office. Patients and inhabitants shared the entrance but once in the interior the main staircase, semi-hidden by sliding panels, led to the first

floor.10 This second level accommodated the public aspect of the Dalsaces' life. The main drawing room is a large, double height volume which is big enough to hold small domestic concerts. At the back of the house, a quieter, more private space with a smaller day room and a small conservatory overlooks the back garden. The third floor was set aside for the bedrooms, all of which gave onto a balcony at the rear of the building. The bedrooms and bathrooms are reached by a gallery, its railing designed as bookshelves, overlooking the double height main drawing room. Finally, a volume on one side of the forecourt contained the service wing with the kitchen and servants' quarters.

The general stratification by uses was not novel, being that of a typical shop or workshop with living accommodation over, combining work and family life under one roof. The novelty lay in the spatial interlocking of the different storeys, the fluid treatment of the interior spaces and the freedom of interior distribution afforded by the steel structure. The treatment of the façade was also novel, as its surface appeared to reflect the ideals of the architectural vanguard of the time: new materials, modern design, standardised elements and an industrialised construction process with the immediate purposes of rapid execution and cost reduction. Nonetheless, the reality was quite different, as although the materials and technical methods were imbued with industrial potential, in a prototype house such as this, without a tried and tested construction system and with the technical insecurity of having no guarantee for the novel products being used, the methods developed for this building were far from industrial. Chareau himself confirmed this with the following remark: "(...) the house is a model made by artisans with pretensions to standardisation".

This led to astronomical costs, both financially and in building time: about 500,000 euros in today's terms and 4 years to completion.

Materials and methods

The photographs of the construction process allow us to see the different stages of shoring up the building as work proceeded. The first stage was to demolish the interior and underpin the upper storey with the new metal structure. The second stage was to remove the façades of the first and second storeys, when the metal frame became the only support for the entire weight of the storey that was preserved. There is a remarkable dichotomy between the design of the framework, made up of stanchions and girders joined by site bolted or riveted metal cleats, which is traditional, bordering on art

nouveau/modernisme,11 and the modern concept of a fluid space in which the bearing structure is clearly dissociated from the internal distribution, leaving the pillars standing free and allowing mobile, folding or sliding partitions to be created. Indeed, particularly on the bedroom floor, most of the partitions open. The doors reach from floor to ceiling and alter the perception of space considerably depending on whether they are open or closed, while their high degree of mechanisation makes the interior highly versatile. In fact, at that time only the Schröeder house had a similar capacity for transformation, although there the transformation of space is total whereas the Maison de Verre normally employs subtle variations that modify the light or the view of space. However, on the bedroom floor there are doors without frames and sliding walls that completely transform the space. Even the design of the installations follows the same criterion. The heating and wiring are separated into two autonomous systems, the heating ducts that pipe hot air along the horizontal planes under the floor structures and the vertical pipes that carry the lighting, power and telephone wiring. These lead from the ground to the roof without touching the walls and have control consoles that hold the sockets and switches. The masonry is thus freed from the task of supporting the installations and the distribution can be altered without affecting them. All this was largely possible thanks to the craftsmanship of Louis Dalbert, a blacksmith who had already worked with Chareau in 1918 on the decoration of a flat for the Dalsaces, the same couple who were later to entrust them with building the Maison de Verre.

This manner of conceiving an architecture enhanced by the use of mechanical contrivances such as the service lift, private lift, retractable stairs between the master bedroom and the day room, etc., gave rise to a machinist aesthetics that suggested to Kenneth Frampton the idea that a technical poetics invades the entire

house.12 The fact is that the appearance of the interior, the floor and wall finishes, the workings of the construction details and the nakedness of the joins, the relations between installations and partitions, etc., strengthen the feeling of being inside a machine for living in and materialise the architectural theories concerning the truth of the construction and the covering formulated by Semper or Bötticher and Le Corbusier's machinist aspirations. Indeed, Le Corbusier felt deep admiration for the Maison de Verre, which he visited while it was under construction, and it undoubtedly influenced subsequent works of his such as the Weekend House in a Paris suburb, the Maison Clarté or the Porte Molitor, where glass block façades, indirect lighting and transformable spaces make their appearance. Chareau solved a problem that acquired moral overtones by deciding to demonstrate the possibilities of the new materials (steel, glass) and radically questioning the very essence of the classical tradition. By accepting the new, light, transparent materials in order to harness their expressive qualities and by superseding the tradition of building that identified enclosure and bearing wall as an insoluble whole, Pierre Chareau dissected supporting structure and covering, breaking doubly with the Vitruvian tradition as seen by the Age of the Enlightenment and imposed by the Academies.

Every machine is composed of parts and in the case of the Maison de Verre the parts are the glass blocks of the façades. They are grouped into construction units, panels, that determine the intermediate scale between the structure and the detail of the design and enable us to understand the underlying logic of the building's construction as well as the manufacturing process that justifies many of the solutions developed by Chareau. They also remind us that the field of construction in itself, far from being just a problem, continues to be a specific source of architectural invention and expression.

Chareau himself gives us the best explanation of the solution he adopted for the façades: "I had to build between two party walls, and the plans called for a division of space according to the needs and tastes of modern living habits. There was only one way to get the maximum of light: build entirely translucent façades. I began experimenting in 1927, using large and thick plates of glass, frosted on one side. This first attempt did not satisfy me at all, though. At any rate, and given the fact that the ventilation and heating problems had been solved in a very special way, the principle of doing away with windows ws adopted: there would be only small openings, for security. At this stage, giving up the idea of using large glass blocks, we began looking for elements which, once assembled, could make unlimited surfaces, but without creating the gaping holes of large glass plates. It was out of the question to think of new materials for such a modest experiment. Among those already existing, I chose Nevada-type glass lenses as they seemed to correspond best to the conditions of the

problem".13

The pragmatism and apparent ease with which Chareau speaks of the way in which he approached and solved the problem of lighting must not blind us to the difficulties he encountered in putting the solution into effect. So much so that the reason why no other building with an all-glass envelope was built between Bruno Taut's Glass Pavilion for the Werkbund exhibition and the Maison de Verre was the lack of technological development. The use of structural glass in France dates back to the end of t he 19th century, although it was confined to small pieces placed in a horizontal grid of reinforced concrete. Later, the technology that enabled them to be placed vertically was developed in Germany, but it was not until 1928 that the French firm of Saint Gobain began to market, with no manufacturer's guarantee, square, 20x20x4 pieces with fluted edges that offered an excellent external finish. However, the company refused to guarantee that its blocks would be self-bearing, so in order to prevent possible breakages of those at the base, Chareau found himself obliged to create a hidden steel grid to group them into panels of 4x6 blocks. These panels became the basic element of the design. Unlike the glass block, a primary, single function product in dimensions that are determined by technical and material demands, the panel, as a standardised building element, is a combination of components into sizes that are determined more by ergonomic than by construction criteria. The four-block width, 91 cm, made it possible to create a façade that contains doors and windows with different opening systems, as well as a large number of interior partitions, hidden panels, translucent or opaque interior doors, low or tall, fixed or moving, which close off almost all the interior spaces through juxtaposition and give the interior and exterior an exceptional unity.

The original design had identical frames on both façades. The mullions were two 30x15 mm channels welded to a 100x9 mm steel plate in order to give the façade rigidity. Horizontally, two channel sections identical to the vertical ones completed the grid that supported the glass block panels. In 1930 Chareau covered this steel framework with a mortar to achieve an apparently seamless surface, without a visible skeleton, as though it were an unlimited transparent plane. However, in the '60s this continuous covering was removed from the main façade and replaced by metal bars that emphasised the interior sub-structure by carrying it through to the exterior. The original look was preserved on the rear façade, where the two original enclosure systems can still be seen. The ground and second floor have the same glass blocks as the front façade but a second type of panel, closer to the curtain wall concept, was employed for the living room and conservatory area on the first floor. The infill material was transparent glass, dry fitted in a steel frame, allowing the light and the sun to pass directly into the interior. The parts were bolted together with a leather seal between them for weather-tightness. The panels were composed of a steel frame into which either a fixed pane of glass or an opening unit sliding on a hidden mechanism were fitted.

Poetics and function

The Maison de Verre's great contribution to the history of architecture hinges on three aspects: standardisation, transformation and transparency.

By its standardisation, the house postulates a modular order with pretensions to mass production. Through this industrialisation of the components, the pieces not only generate a multitude of components that are based on the substitution of variables, they are also interchangeable; in other words, their potential for modification is also a potential for replacement. This potential enables the interior of the house to be transformed by operations that range from pure necessity to subtle poetic variation. An example of these two degrees of transformability in one and the same element is the main staircase from the ground to the first floor. This is in a public zone, a passage used by both the patients visiting the doctor's surgery and the inhabitants of the house. The landing is closed off by a pivoting door that separates the private accommodation from the medical practice in response to a functional need. However, the entire stair space is surrounded by perforated metal screens that transform its perception from transparency to translucency, causing subtle changes in the light that are provided largely for lyrical expression rather than a strictly functional requirement.

Nonetheless, nobody is better qualified than the owner to convey the feeling of living in a glass box such as the Maison de Verre: "Thanks to an old lady who did not wish to vacate her sordid flat on the third floor, Pierre Chareau realised the structural tour de force of three luminous floors within the ground and first floor of this small town house. These two floors had been so dark that the employees of the old lady, who would live to be a hundred, were obliged to work throughout the day by artificial light. Light permeates freely around this block, of which the ground floor is given over to medicine, the first floor to social life and the second to nocturnal habitation. The problem this posed was enormously difficult to resolve. The interpenetration of rooms, some of which ran through two floors (i.e. the consultation room and hall), made the problem of sound insulation very difficult. The ground floor, the professional section of the house, facilitates work and affords the patients, once their first anxiety is over, great calmness. The whole house was created under the sign of amity, in perfect affective

accord."14

It was this convergence of interests between client and architect that enabled the Maison de Verre to be built. It is significant that such a 'connection', particularly when the client is a doctor, has led to the construction of some of the most paradigmatic works of domestic architecture by the vanguard of the first half of the 20th century. To cite only a few: Adolf Loos' villa Karma, Le Corbusier's house for Doctor Curruchet, Richard Neutra's Lovell house, Mies' Farnsworth house or this, Pierre Chareau's Maison de Verre, built for a gynaecologist. It seems that the level of culture is a determining factor in creating a mutual understanding between client and architect that aims to satisfy spiritual aspirations rather than simply building an enclosure to live in.

Art generally employs a medium in order to convey an idea. The medium may be multiple, the ideas expressed are almost unlimited. Architecture, however, must bring the ideas into agreement with utility; poetics and function are not always compatible because bridging the rift between idea and reality is a complicated matter. John Hejduk said that the significant architect is one who, when finished with a work, is as close to the original abstraction as he or she could possibly be. Rather than a theoretical architecture that does not make the leap from paper to materiality, Chareau achieved a work of art in which the idea managed to surmount the technical difficulties without renouncing the degree of abstraction sought by the artistic vanguard of the time.

|

|

|