| Color, ornamento y delito | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Colour, ornament and crime | ||||||

Arquitecto/Architect:

Alfonso Díaz Segura

| La figura de Adolf Loos constituye un paradigma en

la historiografía de los grandes arquitectos del siglo XX. Por un lado se

le considera el precursor revolucionario de muchas teorías materializadas

posteriormente por los maestros del Movimiento Moderno, pero por otro, se

ha tendido a simplificar las características formales y semánticas de su

obra en aras de una mejor inserción en el esquema historiográfico lineal

que explicaba la evolución continuista de Ledoux a Le Corbusier o de

Morris a Gropius. Y si esto se ha demostrado en estudios posteriores como

un error de método propiciado por la voluntad hagiográfica de

historiadores como Philip Johnson o Sigfried Giedion en el caso de los

míticos maestros del Movimiento Moderno, lo es mucho más si cabe en el

caso de Adolf Loos, personaje contradictorio, polémico e inclasificable

por definición. Tan sólo si reducimos la arquitectura de Loos a la

imagen icónica de sus fachadas blancas, despojadas de ornamento,

encontraremos evidentes analogías con otras del más puro "estilo

internacional". Pero el proceso intelectual mediante el cual Adolf

Loos alcanza esta formalización no es en absoluto análogo al de otros

maestros del Movimiento Moderno1. Por eso durante largo tiempo la

arquitectura de Loos ha sido clasificada de "preracionalista"

desatendiendo a otros parámetros conceptuales y espaciales que sí

definían y cualificaban por completo su obra. Uno de estos conceptos,

enunciado como "poética de la alteridad" 2 o poética

de la contradicción es el que justifica la presencia de este

artículo en una monografía sobre el color.

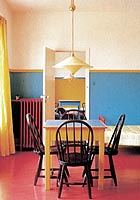

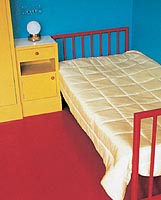

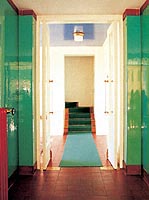

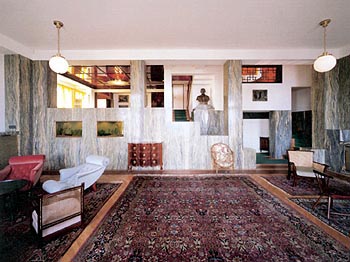

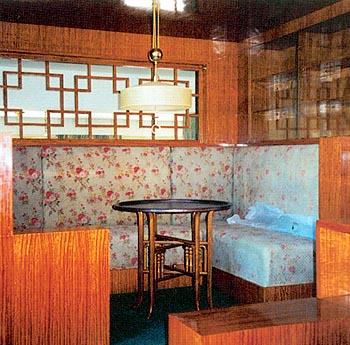

La contradicción como protección frente a la sociedad La arquitectura de Loos no responde a una voluntad de reelaboración lingüística constante, a la manera en que las vanguardias operaron la ruptura con la estética precedente. Antes bien, es un proceso lento de reflexión y puesta en práctica que le lleva, como final de un largo itinerario proyectual, a crear formas plásticas que tan pronto se acercan como se alejan de aquellas otras icónicas de la arquitectura moderna. Encontramos puntos tangenciales de contacto en las fachadas blancas y mudas de Oud, Gropius o el primer Le Corbusier... pero no responden a una voluntad de militancia en lo moderno3, puesto que cuando la arquitectura moderna da un giro hacia la transparencia, siguiendo la estela profética del ensayo Glasarchitektur de Paul Scheerbart, Loos mantiene su postura de continuar un proceso racional de proyectar según unas reglas propias, que acaban distanciándolo de las arquitecturas weimarianas de Taut, Gropius, Mies y tantos otros. Cuando los arquitectos más aventajados revestían de vidrio sus casas, desdibujando los límites entre interior y exterior, Loos interponía muros cada vez más opacos e inexpresivos entre la ciudad y el hogar. Ambas posturas compartían un sistema proyectual que partía del interior y acababa manifestándose en el exterior, concediendo una mayor importancia al interior e invirtiendo el proceso académico de composición4. Pero mientras los primeros pretendían potenciar la transparencia con cerramientos ligeros, generando un flujo espacial centrífugo, Loos sólo expresaba al exterior la existencia de un complejo interior a través de huecos asimétricamente dispuestos. Concebía arquitecturas centrípetas en las que la verdadera esencia se descubría a fuerza de penetrar en un interior recóndito. Para entender a Loos hay que entender su tiempo, el cambio de siglo, y su ciudad, Viena. Se trata de una época crucial en centro Europa, donde están cayendo las estructuras sociales del Antiguo Régimen aristocrático, y los jóvenes descendientes de la burguesía industrial que ha posibilitado tal cambio intentan encontrar su identidad en la confrontación directa con la estética de la generación anterior5. Es el tiempo del Art Nouveau y sus derivaciones nacionales: modernisme, liberty, jugendstyl, sezession... que como vemos se tratará siempre de movimientos en donde el carácter de novedad, juventud o libertad impregnan incluso el propio nombre-slogan. Los jóvenes burgueses acudían a arquitectos de prestigio para que diseñaran su casa, la decoración interior, y hasta la ropa que debían llevar para no desentonar con el ambiente, lo cual llevó a Loos a satirizar esta conducta en su artículo "De un pobre hombre rico",donde relata el exceso de celo estético que sufrían los arquitectos de la Sezession: "[...] a poco llegó el arquitecto para comprobar que todo estaba en orden y para dar respuesta a cuestiones difíciles. Entró en la habitación. El dueño le salió contento al encuentro pues tenía muchas preguntas que formular. Pero el arquitecto no advirtió la alegría del dueño. Había descubierto algo muy distinto y palideció: -Pero, ¡qué zapatillas lleva usted puestas!, exclamó con voz penosa. El dueño miró su calzado bordado. Pero respiró aliviado. Esta vez se sentía totalmente inocente. Las zapatillas habían sido confeccionadas fielmente de acuerdo con el diseño original del arquitecto. Por ello replicó con aire de superioridad: -¡Pero, señor arquitecto, ¿lo ha olvidado? Las zapatillas las ha diseñado usted mismo! -¡Ciertamente!,-tronó el arquitecto-, pero para el dormitorio. Usted está estropeando todo el ambiente con esas dos horribles manchas de color. ¿No se da usted cuenta? El dueño de la casa lo vio inmediatamente. Se quitó rápidamente las zapatillas y se alegró tremendamente de que el arquitecto no encontrara imposibles también sus calcetines. Se dirigieron al dormitorio donde el hombre rico pudo volverse a calzar las zapatillas" 6. La moraleja es inmediata: cada cual debe poder hacer lo que le plazca en el interior de su casa, sin estar sometido a la presión estética de la sociedad. Por eso Adolf Loos protege a los habitantes de sus viviendas con cerramientos opacos, inexpresivos y abstractos, para responder al despliegue de fatua ornamentación que había proliferado a lo largo de la Ringstrasse durante el siglo XIX con alardes neobarrocos y se desplegaba entonces por toda la ciudad con los diseños sezessionistas, para acentuar la sensación de extrañamiento del transeúnte o del ciudadano, para ocultar la vida privada de sus inquilinos de las miradas curiosas de la gente, para que cada cual pudiera decorar su casa con libertad. De ahí que los muros de cerramiento en la arquitectura de Loos cumplan una doble función: por una parte protegen al habitante del exterior y por otra sirven de soporte para la expresión del mal gusto subjetivo de cada cual en el interior 7. Es decir, son barreras físicas y psicológicas. Para Loos la casa es un templo del habitar, un lugar sagrado que hay que proteger de intrusos y miradas ajenas con el fin de poder desarrollar en su interior una vida libre y sin ataduras respecto a los demás. El propio Loos lo dejaba claro cuando decía: "La casa no debe expresar nada al exterior. Toda su riqueza debe manifestarse en su interior" 8.El color y los materiales El caso de la villa Müller es el más paradigmático porque constituye el cúlmen del largo itinerario proyectual iniciado en la villa Rufer. En ella, tanto la esquizofrenia del muro, blanco al exterior, coloreado al interior, así como la volumetría interior, alcanzan sus cotas más altas de complejidad y refinamiento. En ella las cuatro fachadas poseen el mismo grado de abstracción debido a que todas son visibles con distintos ángulos desde la calle. Continuando con su coherencia proyectual traslada las barreras abstractas de la casa a todas sus caras, y vuelca el contenido psicológico y emocional en la articulación espacial y los revestimientos interiores, para reforzar la separación entre exterior público (profano) y el interior privado (sagrado). Loos concibe el proyecto dotándolo de un marcado carácter emotivo para manifestar la penetración del individuo en un mundo privado, íntimo. Y para ello se sirve de un recorrido cuidadosamente estudiado que nos lleva desde la calle a las entrañas de la casa a través de una verdadera promenade arquitectónica; es decir, manipula las circulaciones para dotarlas de un alto valor psicológico que nos haga percibir el interior de la casa gradualmente y de una forma controlada. Cada espacio interior posee unas dimensiones propias relacionadas con el carácter y el uso que se le va a dar, de forma que se crean células con alturas diferentes pero conectadas entre sí, logrando cierta autonomía entre ellas, pero manteniendo relaciones visuales y funcionales. Así nos encontramos con que no hay una altura de techo constante y que las pequeñas diferencias de nivel se salvan con escalones que comunican las zonas funcionalmente complementarias. Esta articulación espacial es lo que se conoce como Raumplan, y se da casi exclusivamente en la planta noble de la casa. Loos excava el interior de un prisma puro

como si de una gruta se tratara, otorgando cualidades psicofuncionales a

cada pieza de manera que cada habitáculo se diseña en forma, proporción

y acabados para transmitir un estado de ánimo determinado. En la villa

Müller tenemos dos ámbitos de la casa en los que se produce esta

relación espacial reforzada por los acabados de las paredes. En el

espacio del salón y el comedor encontramos con seguridad el mejor y más

logrado de los interiores loosianos. Accedemos a la vivienda a través de

un minúsculo vestíbulo, subimos por una estrecha escalera y tras un giro

obligado para aumentar la sensación teatral del recorrido, desembocamos

en el amplio y luminoso salón, que ocupa el tercio posterior de la

vivienda. Acabamos de penetrar en el corazón de la casa. Desde el punto

en que nos hallamos divisamos el salón en frente y un par de escaleras

que parten en cada dirección, una a derecha y otra a izquierda. El salón

está separado del espacio de circulación mediante un muro perforado que

ha quedado reducido prácticamente a los macizos que marcan el ritmo de

los pilares. A través de estos limpios cortes geométricos las paredes

dejan ver el complejo ensamblaje de escaleras que organizan recorridos y

articulan espacios, posibilitando la unidad perceptiva de los diferentes

ambientes. Algo similar ocurre en el segundo ámbito de la vivienda en donde se desarrolla el Raumplan. Si cogemos desde el salón la escalera de la izquierda llegaremos a las salas privadas de los señores Müller, que se divide en dos zonas claramente diferenciadas: el saloncito o sala de conversación, bien iluminado y revestido de madera satinada clara, y tres escalones por encima la biblioteca, más recogida y por ello de menor altura, revestida de oscuros paneles de caoba. Como vemos el empleo de materiales cuidadosamente seleccionados por su color y textura, refuerza el carácter de privacidad de las estancias, puesto que se concibe cada zona de la casa en función de la sensación que se pretende conseguir: "[...] el artista, el arquitecto, siente primero el efecto que quiere alcanzar y ve después, con su ojo espiritual, los espacios que quiere crear. El efecto que quiere crear sobre el espectador, sea sólo miedo o espanto como en la cárcel; temor de Dios como en la iglesia; respeto del poder del Estado como en el palacio; piedad como ante un monumento funerario; sensación de comodidad como en casa; alegría como en una taberna; ese efecto viene dado por los materiales y por la forma" 9.E indiscutiblemente, me atrevo a apostillar, por el color. |

Adolf

Loos is a paradigmatic figure in the history of the great architects of

the 20th century. While he is considered the revolutionary forerunner of

many theories that were later put into practice by the masters of the

Modern Movement, there has been a tendency to simplify the formal and

semantic aspects of his work to fit him better into a linear scheme of

history that sees a continuity of development from Ledoux to Le Corbusier

or from Morris to Gropius. If later studies have shown this to be a

methodological error caused by the hagiographic bias of historians such as

Philip Johnson or Sigfried Giedion in the case of the mythical masters of

the Modern Movement, it is, if possible, all the more so in the case of

Adolf Loos, who is, by definition, a contradictory, controversial and

unclassifiable figure. Only if we reduce Loos' architecture to the iconic

image of his white, unadorned façades can we find any evident analogy

with the works of the purest "international style". However, the

intellectual process by which Adolf Loos reached this formalisation bears

absolutely no resemblance to that of other masters of the Modern Movement1. As a result, Loos' architecture has long been

classified as 'pre-rationalist' and other conceptual and spatial

parameters that do in fact define and describe his work have been

disregarded. One such concept, formulated as a “poetics of otherness”

2 or poetics of contradiction,

justifies the inclusion of this article in a monograph on colour.

Contradiction as protection against society In order to understand Loos one must understand his age, the turn of the century, and his city, Vienna. This was a crucial period in central Europe. The social structures of the aristocratic Ancien Régime were breaking down and the young scions of the industrial bourgeoisie that had made this change possible were attempting to define their identity through direct confrontation with the aesthetics of the previous generation5. It was the time of Art Nouveau and its national offshoots: modernisme, stile liberty, jugendstil, sezession ... in all these movements the notion of novelty, youth or liberty imbues even their name or slogan. The youth of the bourgeoisie commissioned well-known architects to design their houses, their interior decoration, even the clothes they should wear to fit in with their setting. Loos caricatured their behaviour in his "Poor Little Rich Man", where he recounts the excessive aesthetic zeal of the Sezession architects: “[...] soon afterwards the architect arrived to check that everything was in order and answer any difficult questions. He entered the room. The owner went happily to greet him, as he had many questions to ask. However, the architect did not notice the owner's happiness. He had seen something quite different and blanched. "What are those slippers you are wearing!" he exclaimed in a pained tone of voice. The owner looked at his embroidered slippers and breathed a sigh of relief. This time he was completely innocent: the slippers were a faithful copy of the architect's original design . So he answered with a superior air: "But Herr Architect, have you forgotten?" You yourself designed these slippers!" "Certainly!", thundered the architect, "but for the bedroom! You are ruining the whole atmosphere with those two horrible splashes of colour. Do you not realise?" The owner of the house saw it immediately, quickly took off his slippers and was tremendously glad that the architect did not find his socks impossible as well. They went to the bedroom, where the rich man was able to put his slippers back on” 6. The moral is obvious: people may do as they wish inside their own home without being subjected to the aesthetic pressures of society. That is why Adolf Loos protects the inhabitants of his houses with opaque, expressionless, abstract envelopes: to combat the display of fatuous ornamentation that had proliferated with neo-baroque ostentation all along the Ringstrasse in the 19th century and was spreading throughout the city at that time with the sezessionists' designs, to protect his occupants from prying eyes and to allow each and everyone to decorate their houses as they wished. Consequently, the outer walls in Loos' architecture fulfil two functions: firstly, to protect the inhabitants from the exterior and, secondly, to provide a background for each person's expression of subjective bad taste in the interior7. In other words, they are physical and psychological barriers. For Loos, the house is a temple of habitation, a sacred place that must be protected from intruders and peeping eyes so that a free life, unfettered by others, can be lived inside it. Loos himself made this quite clear when he said: "The building should be dumb on the outside and reveal its wealth only on the inside" 8. Colour and materials The case of the Müller house is the most paradigmatic as it is the culmination of the long road that began at the Rufer house. Here, both the schizophrenia of the wall - white outside and coloured inside - and the volumes of the interior reach a peak of complexity and refinement. The four sides are all equally abstract because all of them are visible from the street, from different angles. Continuing the coherency of his design, he moves the abstract barriers of the house onto all its faces and pours all the psychological and emotional content into the spatial articulation and coverings of the interiors, thus reinforcing the separation between the public exterior (profane) and the private interior (sacred). Loos' concept gives the building a markedly emotive character in order to express the individual's entry into a private, intimate world. To achieve this, he takes us on a carefully studied route along a veritable architectural promenade from the street to the depths of the house; in other words, he gives the circulation areas great psychological value, manipulating them so that we perceive the interior of the house gradually, in a controlled way. Each interior space has its own proportions, related to its character and the use to which it is to be put: he creates cells with different but interconnected heights, achieving a certain autonomy while maintaining their visual and functional relations. As a result, there is no uniform ceiling height and the small differences in floor level are linked by steps between functionally complementary zones. This spatial articulation, known as Raumplan, is found almost exclusively on the main floor of the house. Loos excavates the interior of a pure prism as though it were a cave, giving psychological and functional qualities to each room: the form, proportions and finish of each space are designed to convey a particular state of mind. In the Müller house this spatial relationship is reinforced by the wall finishes in two areas. The living and dining rooms are undoubtedly where Loos' best and most successful interiors are to be found. The entrance leads into a tiny hallway, followed by a narrow staircase. After the obligatory turn for heightened theatricality, a large, luminous living room occupying the rear third of the building opens our ahead. The heart of the house has been reached. This vantage point offers a view of the living room and two flights of stairs leading in different directions, one to the right and one to the left. The living room is separated from the circulation area by an open wall, practically reduced to the solid blocks that mark the rhythm of the pillars. The clean, geometrical cuts in the wall afford a view of the complex arrangement of stairs that organises routes and articulates spaces, allowing a unitary perception of the different spaces. The dining room, which is smaller, is in direct contact with the living room. It is reached by the right-hand stairs, a flight of five steps that raises it above the level of the living room. The difference in height marks the different character of the two rooms: although connected spatially, they fulfil different social functions. The living room is bigger and higher because it is considered more public than the dining room, which has a more intimate feel. It is in this definition of different atmospheres and sensations that colour and claddings play an essential rôle: cipolin marble from Sion in the living room and mahogany in the dining room. But the veined green marble walls are merely the start of the explosion of colour in these rooms: yellow curtains and a red hearth in the living room, green curtains and the sienite table top in the dining room. A similar effect is achieved in the second

area of the house where the Raumplan is developed. The left-hand stairs

from the living room lead to the Müllers' private area, divided into two

clearly differentiated zones: the boudoir, well lit and clad in a light,

satiny wood and, three steps higher, the library, a more secluded space

which therefore has a lower ceiling and is clad in dark mahogany

panelling. The use of materials that are carefully selected for colour and

texture thus reinforces the private nature of the rooms, as each area of

the house is conceived in terms of the intended atmosphere. “[...]

the artist, the architect, first feels the effect he wishes to achieve

then, with the eye of the spirit, the spaces he wishes to create. The

effect that he wishes to have on the spectator, whether pure fear or

horror as in prison, the fear of God as in church, respect for the power

of the State as in the palace; pity as at a tombstone, a feeling of

comfort as at home or gaiety as in a tavern, is produced by the materials

and the form”9. |

|

|

|

NOTAS/NOTES: 1. Gravagnuolo, Benedetto, Adolf Loos, Ed.Nerea, Madrid 1988, p. 78./Gravagnuolo, Benedetto, Adolf Loos, Ed.Nerea, Madrid 1988, p. 78. [q.v.] 2. Gravagnuolo, Benedetto, Adolf Loos, Ed.Nerea, Madrid 1988, p. 128./ Gravagnuolo, Benedetto, op.cit, p. 128. 3. En el artículo "Regla para el que construye en las montañas", Loos escribe: "Construye lo mejor que puedas[...] No temas ser tachado de inmoderno. Sólo se permiten cambios en la antigua manera de construir si representan una mejora, si no, quédate con el antiguo. Pues la verdad, aunque tenga cientos de años, tiene más relación íntima con nosotros que la mentira que camina a nuestro lado", en Escritos II. 1910-1932, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, pp. 77-79./ In "Rules for Him [sic] who Builds in the Mountains", Loos wrote: "Build as well as you can [...] Be not afraid of being called unfashionable. Changes in the traditional way of building are only permitted if they are an improvement. Other wise stay with what is traditional, for truth, even if it be hundreds of years old, has a stronger inner bond with us than the lie that walks by our side". In Schezen, Roberto (q.v.), quoted at www.anneke.net/Loos/Paper.html 4. Loos, Adolf, "Mi escuela de construcción", en Escritos II. 1910-1932, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, pp. 74-77./ Loos, Adolf, "Mi escuela de construcción" [My School of Building], en Escritos II. 1910-1932, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, pp. 74-77. 5. Schorske, Carl E., "Tensión generacional y cambio cultural", en Pensar con la historia, Ed. Taurus, Madrid 2001, pp. 235-260./ Schorske, Carl E., "Tensión generacional y cambio cultural" ["Generational Tension and Cultural Change"], in Pensar con la historia, Ed. Taurus, Madrid 2001, pp. 235-260. [translation by Isabel Ozores of Thinking with History: Exploration in the passage to modernism, Princeton U. Press, 1998] 6. Loos, Adolf, "De un pobre hombre rico", en Escritos I. 1897-1909, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, p. 249./ Loos, Adolf, "De un pobre hombre rico" ["Poor Little Rich Man"], en Escritos I. 1897-1909, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, p. 249. 7. Gravagnuolo, Benedetto, Adolf Loos, Ed.Nerea, Madrid 1988, p. 188./ Gravagnuolo, Benedetto, op.cit, p. 188. 8. Loos, Adolf, "Arte vernáculo", en Escritos II. 1910-1932, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, pp. 61-69./ Loos, Adolf, "HeimatKunst." [Vernacular Art] 1914. Gravagnuolo, Benedetto. Adolf Loos, Theory and Works, quoted at www.anneke.net/Loos/Paper.htm 9. Loos, Adolf, "El principio del revestimiento", en Escritos I. 1897-1909, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, p. 152./ Loos, Adolf, "El principio del revestimiento" ["The Principle of Cladding"], in Escritos I. 1897-1909, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid 1993, p. Alfonso Díaz Segura. “Profesor de Análisis de Proyectos en la Universidad Cardenal Herrera-CEU”/Professor of “Analisis de Proyectos” in the Cardenal Herrera-CEU University. |