Miguel del Rey

La última lección griega

|

Arquitecto/Architect: Miguel del Rey |

|

|

La última lección griega

|

Last Greek lesson | |

|

|

|||

Viajar por

Grecia siempre tiene algo de iniciático, es como un nuevo bautismo en una

cultura que siendo común y primigenia, el tiempo, la distancia, los

ritmos, el idioma, le han adherido tantas cosas a la versión recibida por

nosotros, que hacen particularmente atractiva la relectura desde el lugar.

Al visitarla de nuevo: las formas y sus ruinas, la luz, la materia y el

espacio, todo aquello que se ha ido forjando en la mente por la lectura y

la imaginación, hacen que la realidad tome un sentido y una dimensión

distinta.

Recorrer la Vía Sacra en Delfos, por ejemplo, no solo es subir su quebrado trazado y aprehender con los sentidos la forma, el ritmo y la disposición de los Tesoros para luego llegar al Santuario y disfrutar las ruinas del templo; es contemplar la inmensidad de un paisaje conmovedor, donde el viento encrespa los verdes y glaucos de sus bosques de olivos y como estos árboles lo llenan todo, texturan el territorio desde las montañas hasta el fondo de los valles, y a lo lejos se confunden los azules del cielo y del mediterráneo en una naturaleza sin fin; naturaleza de la que bebía la Sibila y desde la que obtenía su visión cósmica. |

Travelling around Greece always has something of an initiation about it, it is like a new baptism into a culture which despite being the shared original has accreted so many things in the version we receive, through time, distance, rhythms and language, that a rereading in the place itself is particularly attractive. On visiting it anew, the shapes and their ruins, light, matter and space, and everything that has been wrought in the mind by reading and the imagination, make reality take on a different dimension and meaning. Going up the Via Sacra at Delphi, for example, does not just mean following a winding path and allowing the senses to take in the shape, the rhythm and the arrangement of the Treasuries before reaching the Sanctuary and appreciating the ruins of the temple, it means contemplating the immensity of a moving landscape where the wind ruffles the greens and greys of the olive groves, seeing how these trees are everywhere, texturing the land from the mountains to the valley floors, and how in the distance the blues of the sky and the Mediterranean meld in the endlessness of nature, that Nature of which the Sibyl was said to have drunk and from which she obtained her cosmic vision. |

|

|

|

|||

| La tierra griega y su cultura generan lugares y focos de intensidad insospechada, algunos de ellos de difícil acceso; por ello el viaje debe ser elaborado de manera detenida y paciente. En un reciente viaje, junto a otros compañeros, nos aproximamos a ese mundo algo pretérito de lo griego, donde uno de los viajeros, V. Vidal, veía en las ruinas visitadas “un último episodio estable de la forma”, tomando así un valor singular, por supuesto mucho más interesante que cualquiera de las poco sorpresivas reconstrucciones obscenas de los monumentos del pasado que desgraciadamente proliferan en Epidauro y que pronto veremos en la propia Acrópolis ateniense, por decir dos lugares mágicos. Aunque me refiero a las ruinas, no solo incluyo en ellas las del mundo clásico; incluyo también los restos, y en algunos casos las ruinas, de una modernidad espléndida, y en muchos casos abandonada, que encontramos en las playas o próximas a los paisajes más característicos de esta tierra. |

The Greek land and culture generate places and foci of unsuspected intensity. Some are of difficult access, so the journey must be planned with time and patience. On a recent trip with some colleagues, we approached this somewhat bygone Greek world and one of us, V. Vidal, saw in the ruins we visited a “last stable episode of form”, giving them a unique value, far more interesting of course than any of the obscene but unsurprising reconstructions of monuments of the past that unfortunately proliferate at Epidauros and that we would soon be seeing in Athens on the Acropolis itself, to mention only two magic places. The ruins are not only those of the classical world, they also include the remains, and sometimes the ruins, of the splendid and in many cases abandoned examples of the Modern Movement that we found at the beaches or close to the most typical landscapes of this country. The dramatic quality of the landscape is somehow immersed in the simultaneously epic and nostalgic condition of the past seeming to have always been better than the present, and this at each moment in history, even in this last period of Modernism. With one caveat, however: a possibility of a future is discerned in the landscape, at least in the countryside, there is a potential landscape of great quality, something that we have lost on this western coast of the same sea. Greece is therefore a land where past and future meet and where the present may be a circumstance but is not the principal one. On this tour, some of the places and architectures that made the greatest impact on me were the tourist facilities dating from that Modernism of the 1950s. This is an architecture and a landscape with moments of a rare plenitude, directly linked to the thinking and the works of those experimentalist architects, both in Europe and in the United States, who were producing their best works during those years. |

|

|

|

|

|||

| El

dramatismo del paisaje está algo inmerso en esa condición a la vez

épica y nostálgica de que el pasado parece que siempre ha sido mejor que

el presente, pero esto en cada momento de la historia, incluso en esa

última etapa de la modernidad. Aunque con una condición: se atisba una

posibilidad de futuro en el paisaje, al menos en el rural, hay un paisaje

potencial de gran calidad, cuestión perdida en ésta costa occidental del

mismo mar. Así pues es una tierra, la griega, donde se unen pasado y

futuro, y donde el presente es quizás una circunstancia no principal. De

entre lo visitado, unos de los lugares y arquitecturas que más me

impactaron fueron las instalaciones turísticas de aquella modernidad de

los años 50. Una arquitectura y un paisaje con unos momentos de plenitud

como es difícil encontrar, vinculado directamente con el pensamiento y

las obras de aquellos arquitectos experimentalistas, que tanto en Europa

como en los Estados Unidos están produciendo sus mejores obras en esos

años.

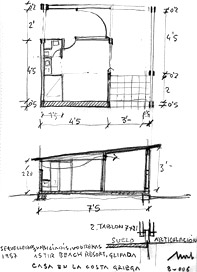

La fecundidad arquitectónica griega de este momento quizás se puede entender tanto por la sintonía ideológica como por el apoyo económico con el bloque aliado tras la Guerra, por el Plan Marshall, o quizás por su fuerte conexión greco-americana a través la emigración a aquel país; no hay que olvidar el sentimiento de apoyo a un país por parte de las potencias triunfantes en deuda al sufrimiento nacional griego en la II Guerra Mundial. Tampoco hay que olvidar esta tierra como bastión occidental en un mundo demasiado próximo al Telón de Acero en una “guerra fría” necesitada de imágenes desde donde propagar un modelo de vivir, en este caso frente a las mismas puertas del Mar Negro, un mar comunista donde se cobijaba la gran flota soviética. Quizás la arquitectura trasmite en sus formas e imágenes una cuestión nacional y pro-occidental frente a otro modelo, el turco, ambivalente en su sentimiento de amor y odio entre la occidentalización y su potente tradición otomana. Visitaremos la obra para infraestructura turística de dos arquitectos principales de estos años: Aris Konstatinidis con sus trabajos para la red de Moteles Xenia en lugares de un particular valor histórico y cultural: Mikonos, Kalampaka, Epidauro, etc., y las obras del equipo formado por Vassiliadis, Vourekas y Sakellarios, en particular el “Astir beach and resort” en Glyfada. Arquitectos presentes en alguna monografía de arquitectura griega editada en España, aunque no demasiado conocidos en el panorama europeo contemporáneo a pesar de haber construido una obra espléndida; obra poco valorada por la propia sociedad griega, ya que salvo las referencias en las guías de arquitectura, no son fáciles de conseguir las monografías de estos interesantes autores, incluso, ni en las mejores librerías especializadas de Atenas. En el caso de Aris Konstatinidis hay dos imágenes de obras de posguerra de una poética interesante: Una casa para fines de semana (1951) y un pabellón en Tesalónica (1952); en la primera el realismo constructivo desemboca en un cierto brutalismo y en ambas está presente una fresca economía de medios. Su aproximación a cultura popular, intentando beber de nuevo en los orígenes de una riquísima arquitectura vernacular, serán los pilares desde donde reinicia un discurso moderno que se aparta de una intención y un discurso típicamente vanguardista, para recorrer caminos donde el experimentalismo toca tierra y se fortalece igual que sucede en el resto de Europa cuando empiezan a reinterpretarse tanto las sensibilidades que provienen del lugar, como a manipularse los materiales que la industria ofrece, olvidándose de la fascinación por lo industrial y deseando obtener los máximos beneficios de un sistema, el industrial, que genera buenos productos a los que el arquitecto adecua para su obra desde muy distintas perspectivas. Quizás una condición a señalar es el discurso compartido de estos arquitectos de mediados del s XX. La trabazón cultural entre su obra y aquellas otras que están construyendo uno de los momentos más atractivos de la modernidad. Por poner unos ejemplos: sus planteamientos espaciales y constructivos al abordar la arquitectura de la casa, tanto en su relación con la tradición constructiva como en los materiales utilizados, tan próximos a la manera como los plantea J. Utzon en sus proyectos de viviendas unifamiliares al norte de Copenhague, o más tarde en sus casas de Mallorca. La correspondencia con ciertos planteamientos seccionales, en este caso con la obra de A. de la Sota y su Residencia Infantil de Verano en Miraflores de la Sierra (1957) que nos viene a la memoria al observar proyecto del hotel Xenia en Kalampaka (1960) de A. Konstatinidis cuando aborda su relación con una particular topografía del lugar. La correspondencia formal con las arquitecturas que en Punta Martinet construirá J. L. Sert a mediados de los años 60, etc... Sin olvidar una cierta conexión americana, aquella que proporcionan la liviandad de las estructuras en el caso de Vassiliadis, Vourekas y Sakellarios, tan próximas a los sistemas de las “case study”, resueltas en este caso en madera pintada de ajustada sección y de cuidado diseño en sus apoyos en el suelo; y que también podemos ver en los interiores de los vestíbulos de los hoteles Xenia, donde encontramos los muebles que Ch. Eames está produciendo en California en fechas coincidentes con la propia presentación del producto, depositados sobre suelos de losas de piedra caliza, dentro de la mejor tradición griega desde la cual en esa época D. Pikyonis esta reelaborando todo un discurso formal en las proximidades de la Acrópolis. De la obra de Vassiliadis, Vourekas y Sakellarios visitamos el proyecto antes citado del motel en la playa de Glyfada (1957). Reemplazando una antigua instalación turística destruida durante la guerra, nos muestra quizás uno de los ejemplos más elegantes de esa modernidad a la que se abrió la Grecia de mediados del s XX. Es una obra donde la arquitectura, su disposición en la misma línea de costa, el paisaje y la intervención sobre el mismo, son un todo. Las relaciones entre los distintos bungalows son interesantes, disponiendo de espacios semipúblicos de gran calidad, así como de atractivas relaciones interior-exterior en cada apartamento, donde aparecen espacios de una ambigüedad encomiable en este tipo de habitaciones. |

The architectural fecundity of Greece at that time may perhaps be understood as a result of being on the same ideological wavelength and of financial support from the Allies after the War, through the Marshall Plan, or perhaps of strong American-Greek connections because of emigration to the USA, not forgetting the feeling among the triumphant great powers that support was owed to Greece for the nation’s sufferings during World War II. Nor should it be forgotten that this country was a bastion of the West in a world too close to the Iron Curtain during a cold war that needed images it could use to radiate a model way of life, in this case before the very gates of the Black Sea, a Communist sea that sheltered the great Soviet fleet. Architecture, through its forms and images, may convey nationhood and being pro-western, as opposed to another model, that of Turkey, with its love/hate ambivalence between westernisation and its powerful Ottoman tradition. Let us look at the tourism-related work of two of the main architects of those years: Aris Konstatinidis, who worked for the Xenia hotel network in places of particular historic and cultural significance such as Mykonos, Kalambaka and Epidauros, and the team of Vassiliadis, Vourekas and Sakellarios, particularly their Astir Beach and Resort at Glyfada. Although these architects are found in some monographs on Greek architecture published in Spain, they are not too well known in the panorama of contemporary Europe despite the splendid works they built, which, indeed, are little prized in Greece itself, as although there are references to them in architecture guides, it is difficult to find monographs on them even in the best specialised bookshops in Athens. In the case of Aris Konstatinidis, there are two images of post-war works that possess an interesting poetry: a weekend home (1951) and a pavilion in Salonika (1952). In the former, constructivist realism leads to a certain brutalism; both have a freshness in their economy of means. Their approximation to popular culture, attempting to drink anew from the sources of a very rich vernacular architecture, provided the pillars on which to recommence a Modernist discourse that distanced itself from any typically vanguard intentions or language and explored paths where experimentalism touched down and was strengthened, as happened in the rest of Europe when the sensitivity arising from the place began to be reinterpreted and people started to manipulate the materials proffered by industry, leaving behind the fascination with everything industrial and aiming to get the most out of an industrial system that creates good products which architects fit to their work from many different perspectives. One factor that might be pointed out is the shared discourse of these architects of the mid 20th century, the cultural interweaving between their works and those of others who were creating one of the most attractive moments of Modernism. For example, their spatial and construction approaches to the architecture of a house, both in relation to the building tradition and to the materials they used, were very close to the way that J. Utzon conceived them in his designs for family houses north of Copenhagen or, later, his houses in Majorca. A correspondence in certain cross-sections, in this case with A. de la Sota’s Children’s Summer Home in Miraflores de la Sierra (1957), comes to mind on seeing the design for the Xenia hotel in Kalambaka (1960) by A. Konstatinidis where he approaches its relation to a particular topographic feature of the site. There is a formal correspondence with the architecture that J.L. Sert was building at Punta Martinet in the mid 1960s, among others. Nor should we forget a certain American connection, that of the lightness of the structures of Vassiliadis, Vourekas and Sakellarios, which are so close to the Case Study systems, worked out in this case in painted wood of pared-down dimensions with carefully designed ground supports. It can also be seen in the lobbies of the Xenia hotels, where we find the furniture that C. Eames was producing in California set down, at around the date when the products were brought out, on limestone slab floors in the best Greek tradition - the tradition that D. Pikionis was reworking into an entire formal discourse in the environs of the Acropolis during that same period. Of the works of Vassiliadis, Vourekas and Sakellarios, we visited the Glyfada beach hotel complex (1957). Built to replace a hotel destroyed during the war, it is perhaps one of the most elegant examples of the Modernism to which Greece became receptive in the mid 20th century. It is a work where the architecture, its shoreline position, the landscape and the intervention in the landscape form a whole. There are interesting relationships between the bungalows, which have semi-public spaces of great quality, as well as attractive interior-exterior relationships in each apartment, where spaces of an ambiguity that is praiseworthy in this type of rooms make their appearance. The view of the cape Glyfada complex from the curving beach shows a landscape that is fragile but well worked-out despite the apartments’ proximity to the shoreline. It follows certain rules of good layout, both in the shapes and their dimensions and in the rhythm of their distribution in space, where the tops of the pine trees are always more than double the roof height of the bungalows, which are grouped into rows of four or five. The scale of the groups of apartments should be mentioned, as should their being placed on terraces raised on stone walls, the same as build the wall fragments which form part of the envelope of the apartments themselves. The groups of bungalows colonise a wood, achieving an attractive balance between nature and artifice. However, the layout of the small apartments, their indoor/outdoor relationship, their dimensions and cross-sections and the materials in which they are realised are probably what most stays in the mind after visiting this place. This is not a vanguard work, far from it, but the architecture has not lost that idea of society. In this case it attempts to pin down an image that may be half way between an approximation to the American way of life and a social democrat utopia in the waters of the Mediterranean. Pictures from the time are practically a manifesto for a lifestyle. In the use of materials, the dosage of local and industrial materials should be pointed out: the white lime of the walls is combined with tightly designed wooden columns composed of two sections joined by connecting pieces that increase its resistance, a design that also makes for easy connection with the wooden joists, which are all painted white, well protected, off the ground and joined together by galvanised steel components. A light metal roof rests on wooden battens which have angled ends, preventing excessive exposure to the weather and increasing the impression of lightness. Air is allowed to pass between the low-pitched roof and the ceiling to ventilate the cavities and cool the rooms on hot days. Consequently, we find an interest in skill and details, in shapes made by skilled trades that can adapt what industry provides. The reality of the construction is austere and so necessary that it brooks no questioning in its formal coherence. The forms are stabilised and take shape through the fragments of limestone wall that join the architecture to the ground and speak of this physical and cultural place. The distribution of the interior space is effective: a border of services and a single room where the sleeping space is set at one end, leaving an area for daytime use that allows of multiple configurations through possible expansions towards the outdoor spaces, towards the balconies. The joinery is complex: sliding doors and revolving screens open up the space and connect interior and exterior, drawing us at will into semi-public spaces or allowing us the privacy that is desired on occasion in this type of abode. Of the work, we are left with a ruin that is excessively close to us: it has not yet reached a sufficient degree of stability for us to see the beauty that we can only appreciate when the lines and materials have been refined by time. Its condition of utility, its concreteness, are still to close for us to be able to distance ourselves in time and submerge ourselves in the aesthetic transformation which first denudes the forms of everything that is superfluous to them and then turns them into pure lines and into matter that little by little is returned to nature. |

||

|

|||

|

La vista del conjunto del cabo de Glyfada vista desde la concha de la playa nos presenta un paisaje frágil pero resuelto de manera ajustada a pesar de la proximidad de los apartamentos a la línea del mar; allí encontramos ciertas reglas propias de una buena disposición, tanto por las formas, como por sus dimensiones y por el ritmo de los elementos distribuidos en el espacio; procurando siempre que las copas de los pinos superen en doble de altura de cubierta de unos bungalows adosados en grupos de cuatro o cinco unidades. Hay que destacar la escala de los grupos de apartamentos y su ubicación en terrazas levantadas por muros de piedra , los mismos que construyen los fragmentos murarios que cierran en parte los propios apartamentos. Estos grupos de bungalows colonizan un bosque donde se obtiene un atractivo equilibrio entre naturaleza y artificio. Pero es quizás la planta de los pequeños apartamentos, su relación interior-exterior, la métrica, su sección constructiva y los materiales que concretan la obra, lo que se queda más grabado tras una visita al lugar. No se trata en este caso de una obra de vanguardia; está alejada de esa condición, pero la arquitectura no ha perdido aquella idea de lo social, en este caso se trata de concretar una imagen que quizás esté a mitad de camino entre una aproximación al modelo americano de vivir o a la utopía socialdemócrata en las aguas del mediterráneo. Las imágenes de la época son todo un manifiesto de un estilo de vivir. En el uso de los materiales hay que señalar la dosificación entre aquellos que provienen del lugar y aquellos que provienen de la industria; así, junto a la caliza blanca de los muros, encontramos el ajustado diseño de pies derechos de madera compuestos de doble perfil unido por conectores que aumentan la inercia del soporte, cuyo diseño nos permite la conexión fácil con la viguetería de madera, toda ella pintada en blanco, bien protegida, aislada del suelo y ensamblada entre sí por piezas de acero galvanizado. Una cubierta metálica y ligera se apoya sobre un entrevigado de madera acabado en un pico de flauta que evita su exposición excesiva al exterior y aumenta su ligereza visual. Entre la cubierta, ligeramente inclinada, y el trasdós interno del techo, se permite el paso del aire para la ventilación de las cámaras y la aclimatación de las estancias en los días calurosos. Encontramos pues, un interés por el oficio y los detalles, por las formas realizadas a través de oficios diestros que manipulan aquello que ofrece la industria. Su realidad constructiva es austera y tan necesaria, que no admite duda en su coherencia formal. Formas que se estabilizan y tomas cuerpo a través de los fragmentos de muros de caliza que la unen la arquitectura a la tierra y nos hablan de ese lugar físico y cultural. El espacio iunterno nos presenta una distribución eficaz: un borde de servicios y una estancia única donde se dispone el espacio para dormir en un fondo, quedando un área para el uso diurno que permite múltiples configuraciones a través de posibles expansiones hacia los espacios exteriores, hacia las terrazas. Una Carpintería compleja de puertas correderas, mamparas giratorias que nos abren el espacio y conectan exterior e interiores, nos aproximan cuando lo deseamos a los espacios semipúblicos, o nos permiten esa privacidad deseada en ocasiones en este tipo de habitáculos. De la obra nos queda una ruina excesivamente próxima, que aún no ha llegado a un grado de estabilidad adecuado para poder apreciar esa belleza que solo podemos disfrutar cuando la traza y la materia es depurada por el tiempo. Está demasiado próxima su condición de utilidad, su concreción, para que podamos distanciarnos en el tiempo y sumergirnos en la transformación estética que tras desnudar las formas de todo aquello que le sobra, las convierte en pura traza y en materia que es devuelta poco a poco a la propia naturaleza. Miguel del Rey Arquitecto. Catedrático de Proyectos en la UPV |

|||

|

|