Nothing new under the sun

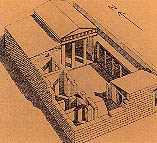

The concept of solar architecture is nothing new. In our Western culture,

the first documented references date from ancient Greece. Xenophon quotes Socrates1:

"in south-facing houses, the sun enters through the portico in winter while in

summer the path of the sun, as we have described, rises overhead and over the roof, thus

there is shade"

In the same way, he mentions the importance of closing the house on the

north-facing side as a barrier against cold winds, of the eaves that provide protection

from the rays of the sun in summer, etc.

These were the beginnings of a "solar" methodology and these

concepts were known and applied when planning houses and even cities. In the 5th

century B.C., the extension of the city of Olinthos (one of the main cities in northern

Greece during the Hellenistic period, on a similar latitude to New York) is a clear

example of how the Greeks practised solar architecture and urbanism. Aristotle mentions

that rational planning of this kind enabled the houses to be laid out to best advantage to

obtain the maximum benefit from the sun2.

A number of archaeologists agree that solar architecture was a primary

consideration for the builders of classical Greece.

We may also mention the architecture and urbanism of ancient China, the

methods used in the arid climates of the Middle East and North Africa to cool the rooms or

the urbanism of the 18th and 19th centuries, when the regulations

defended the right of buildings to sunlight. We need go no further afield than a walk in

our own countryside to observe the layout of the rural buildings: south-facing, few

openings on the north side, walls with high thermal inertia, etc.

Historically, we can continue our journey through the teachings of great

masters of solar architecture such as Vitruvius, Faventinus, Palladio and so many others

that it is impossible to mention them all.

Finally, let us listen to what Aeschylus had to say about the

"barbarians" whose buildings did not follow the criteria he defined as

"civilised"3:

"Although they had eyes to see they saw in vain; they had ears but

did not understand. Like shapes seen in dreams, throughout their time they aimlessly cast

around all things in confusion. They lacked the knowledge of houses ( ... ) turned to face

the sun and lived ( ... ) like swarming insects in sunless caves."

What we have forgotten

Together with the development of science and technology, the century that

is coming to an end has brought us a blind faith in them: they can solve everything. The

mirage of the unlimited abundance of conventional sources of energy makes us believe that

we can generate our environment artificially and estranges us from the natural

environment.

The way in which we build nowadays is none other than a faithful

reflection of this way of thought. In this century we have discovered that we can build in

a manner that does not depend on the conditions that surround us, since we can create our

climate through air conditioning and heating and our light through artificial lighting. We

are no longer surprised when developments relegate dwellings to facing gloomily northwards

or in a direction where the neighbouring buildings cut out any sun.

Additionally, because building has become an industrial activity, there is

a distance between the user of the dwelling and the process of creating and building it

which never existed in previous times, when a folk wisdom existed and was handed down from

one generation to another.

All this has led to knowledge that was rooted in our civilisation and in

our architectural culture being despised as of little importance.

A reflection

One of the main reasons for this discontinuity buries its roots in our

economic system. In our society, the technologies that dominate and end up developing

further are those that bring profit to the dominant economic structures.

The development of an integrated architecture makes individuals less

dependant on the mechanisms of consumption and, in general, on the movements of the

economic markets. We must remember that the building industry is one of the main sectors

of our economy. Consequently, it seems logical that our production systems have not

concerned themselves with helping these processes to prosper.

During periods in which solar architectures have been at their height, why

have they been cut short by policies that acted against them?4.

Why, nowadays, are active solar installations the only ones to be

subsidised? (These are the ones that employ installations added to the building to provide

energy, as opposed to passive solar architecture where it is the construction of the

building itself that supplies it and this does not enjoy any kind of subsidy).

Why are great aeolian energy power stations now proliferating rather than

individual wind-powered installations or ones that are closer to where the energy is

consumed? Particularly since the efficiency of the big stations is far lower than that of

the latter as a large part of the energy is wasted during the transformation and

distribution processes.

Rediscovering the balance

I would like to centre the following considerations around the thermal

aspects of architecture, although I am aware that there are many other important questions

concerning the integration of the building with nature.

It is merely a question of approaching such aspects with the same

rationality with which we normally approach other facets of the building process.

A correctly aligned building5 with appropriate

insulation has already gone a long way towards the goal. If we take as our base line the

energy costs required by a conventional building, insulated according to current

regulations and sited at random, the energy consumption will be reduced by at least 30%.

Without spending any money.

In climates far harsher than our own, solar architecture habitually

achieves heating energy savings of 70%. In our climate we could be closer to 90%. This

means that we can do away with a conventional heating system.

It is important to point out here that this is without any loss of

comfort. On the contrary, the comfort is far greater because we have created conditions

and balances of which conventional systems are incapable.

All that is needed is to strike a balance between the heat generated by

solar collection, the degree of thermal insulation and thermal inertia. The latter is the

key to a building functioning well thermally.

As regards solar heat collection, a surface that is perpendicular to the

sun’s rays receives over 1.3 KW/h/m2. Bearing in mind the reduction due to the

atmosphere, clouds, the angle of the surface and the transmission through glass, we can

calculate the heat caught by glazed surfaces. According to the author Edward Mazria6, a passive solar building will need around 0.11 to 0.25 m2 of

south-facing glazing per m2 of net floor area. As everyone knows, the entry of solar

radiation through glass causes a greenhouse effect. This means that the wavelength of the

visible spectrum passes through the glass but when it falls on the materials in the

interior it is transformed into infra-red rays, for which glass is an opaque material.

Solar heat collected by the windows of the building is far more effective

than solar panel based heating systems.

As well as reducing energy loss, good insulation evens out internal

temperatures. By placing the insulation on the external face of the building, on the one

hand we eliminate thermal bridges and, on the other, transmit the majority of the thermal

inertia benefits of the envelope to the interior of the building.

With appropriate thermal inertia we turn the building itself into a heat

accumulator which can conserve heat for days and protect us from sudden variations in

temperature. This is the great oblivion of our regulations, which do not envisage that

thermal aspects are always dynamic processes.

All this is also valid in relation to summer climate control. Appropriate

thermal inertia regulates the temperature, and this tends towards the average temperature

over a long period of time (this is the effect we perceive as we enter a typical old

village house). Nature is remarkably well designed, as the movement of the sun means that

south-facing windows catch the sun less in summer than in winter. There are two reasons

for this: the angle is more oblique and solar radiation is slightly higher in winter than

in summer. In our latitude, the angle of the sun’s rays in the months from May to

August is over 70º. Consequently, by providing just a little protection we can avoid the

sun entering.

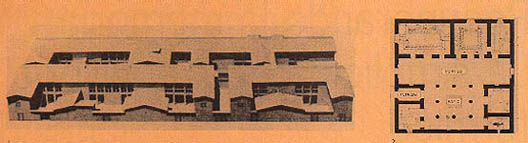

As may be deduced from all this, such an architecture is not at odds with

any style. We must begin to forget the idea that solar architecture is necessarily

suffused with rural overtones or alternative aesthetics.

We architects can rationalise this knowledge and improve the conditions in

our buildings. The benefits are obvious: thermal control systems consume the majority of

the energy in a building and, as we have said, we can achieve greater levels of comfort.

The additional costs are more than compensated for through the savings achieved by doing

away with conventional heating and cooling systems.

This is only the basis and there are manifold possibilities that can be

applied to complement these principles according to the particular project under

consideration.